Shirley Jackson, Madeleine L’Engle, and Motherhood

I read much of Shirley Jackson’s memoir of raising four children, Life Among the Savages (1952), on a weekend when I was caring for three children. For a brief stretch—maybe five pages—we achieved a fragile equilibrium and they were all attached to me as I read. The eight-year-old snuggled against me reading his own book. The six-year-old sat on my lap, idly turning pages I didn’t want turned, and I had made the mistake, earlier, of telling him that Shirley Jackson’s husband seemed kind of terrible, so he interrupted me to ask exactly how he had been terrible.

“He didn’t help with the kids or the cooking or the cleaning,” I said, leaving out the affairs and trying to find my page. My son didn’t seem sufficiently horrified, so I added, “He didn’t think men should have to do those kinds of jobs.” He put his hand over his mouth and giggled. “But what else?” he asked. Wasn’t that enough?

The four-year-old, my nephew, was pressed against my other side, gazing at the ceiling with his legs up the back of the couch, kicking and sucking his thumb. He was in my charge because his sister had just been born and his parents were still at the hospital. My husband, who is rarely away and does do those kinds of jobs, was away. I should have been folding laundry. If I hadn’t been reading a library copy, I would have written the same note in the margin over and over: “Yes!”

In Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (2016), Ruth Franklin writes, “. . . Jackson’s voice makes these stories compulsively readable: many of the fan-mail writers looked upon her as their new best friend. The persona she created was both charming and approachable, a mother at once loving and perennially distracted.”

What a relief it was for me, on this particular weekend, to put off cleaning the kitchen for the third time that day and to read, instead, of the disasters that befell the family when Jackson’s husband went out of town. The furnace stops working, and then the car won’t start and is towed to the garage, so she has to call a taxi to take the kids to school. But as Franklin says, it’s all about voice. The children’s dialogue is remarkable. As Jackson tries to start the car, two of them fight loudly and the youngest chants a nursery rhyme, forming a carefully constructed counterpoint. Jackson tries, ineffectually, to resolve the conflict between the elder two.

‘Old Mother Hubbid,’ Sally swept into the silence, ‘she went to the cubbid to get her dog something to eat, and when she started to get breakfast she had oatmeal.’ She began to laugh wildly. ‘Oatmeal,’ she repeated helplessly, ‘oatmeal.’

I pressed the starter and pulled out the choke.

‘Won’t the star cart?’ Jannie asked. Laurie began to shriek with laughter and after a bewildered minute Jannie joined in. ‘Old Mother Hubbid—’ Sally began.

And what mother couldn’t relate to this wry aside, delivered at the end of a challenging shopping excursion with the kids: “I looked at the clock with the faint unconscious hope common to all mothers that time will somehow have passed magically away and the next time you look it will be bedtime.”

Many of these stories were first published in women’s magazines such as Good Housekeeping. Franklin considers Jackson the precursor of Erma Bombeck and the inventor of “. . . the form that has become the modern-day ‘mommy-blog.’” (Before her biography came out, Franklin wrote about the reissue of Savages in the New York Times.) As an occasional mommy blogger myself, I can live with that lineage.

Knowing the darkness of Jackson’s fiction, the difficulties of her marriage, and the struggles of her life adds an uncomfortable but at times delicious layer of irony to reading this work. As Franklin puts it,

It is the enduring question of Shirley Jackson’s career. How could she simultaneously write the dark, suspenseful fiction that would define her legacy . . . and the warm, funny household memoirs that brought her fame and acclaim in the 1950s but have largely been forgotten since?

Conspicuously absent from her memoir is her writing vocation, except for a funny and infuriating episode in which she checks into the maternity ward to have her third baby and tries to list her occupation as writer. “I’ll just put down housewife,” says the clerk. It’s left to her biographer to convey her dedication to her craft and how she fit it into her family life.

Not so with Madeleine L’Engle, who wrote about family life and the writer’s life in A Circle of Quiet, the first volume of her memoirs. Jackson and L’Engle were born two years apart, and both left New York City when their children were young to raise them in the country—Jackson in Vermont and L’Engle in an old farmhouse in Connecticut. The moves were only seven years apart. Both share stories of small-town life and make their children charming characters. But Jackson wrote her memoir while she was in the thick of parenting young children, and L’Engle wrote hers in 1972, so was able to look back, reflect, and jump around in time. She writes, of the years when her children were young:

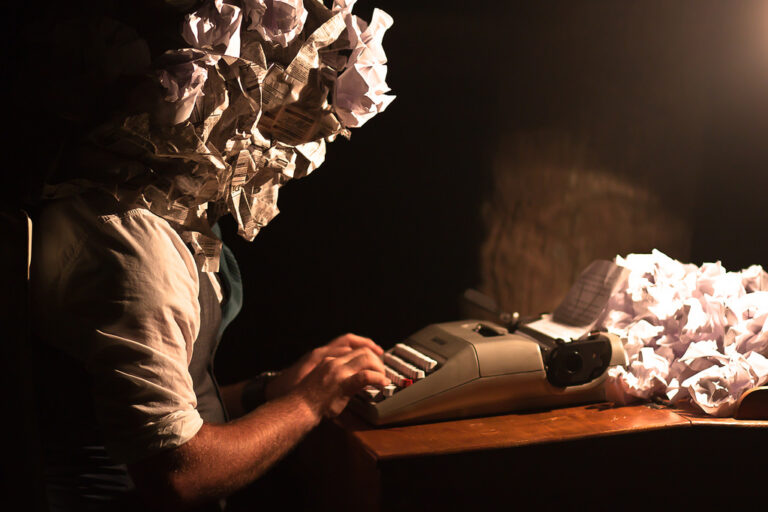

Sometime, during those years, I read The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit. What I remember from it is the reference to “the tired thirties.” I was always tired. So was Hugh. During the decade between thirty and forty, most couples are raising small children, and we were no exception. Hugh was struggling to support his growing family in the strange world outside the theatre. And there was I, absolutely stuck in bucology, with the washing machine freezing at least once a week, the kitchen never above 55° when the wind blew from the northwest, not able to write until after my little ones were in bed, by which time I was so tired that I often quite literally fell asleep with my head on the typewriter.

L’Engle was Christian, and her books explore Christian themes. Jackson was married to a committed atheist and was fascinated with the occult. And yet both wrote in a fantastical vein and both had a lot to say about conformity. They shared a tremendous respect for and delight in their children, while thinking nothing of using them for copy. Jackson kept careful notes of her children’s conversations and used them in Savages. L’Engle was often asked why she wrote for children.

Sometimes I answer that if I have something I want to say that is too difficult for adults to swallow, then I will write it in a book for children. This is usually good for a slightly startled laugh, but it’s perfectly true. Children still haven’t closed themselves off with fear of the unknown, fear of revolution, or the scramble for security. They are still familiar with the inborn vocabulary of myth.

L’Engle, too, obscured some inconvenient facts. In a 2004 New Yorker profile, Cynthia Zarin writes that “L’Engle’s family habitually refer to all her memoirs as ‘pure fiction,’ and, conversely, consider her novels to be the most autobiographical—though to them equally invasive—of her books.” Her husband, Hugh, is lovingly portrayed in A Circle of Quiet, and L’Engle describes herself as happy at age fifty-one. But according to Zarin, Hugh was drinking heavily during this time and “embroiled in at least two affairs.”

These women, imperfect as they certainly were, have served as my friends and guides in motherhood and writing. So what do I make of their half-truths, omissions, and outright lies? Maybe it’s the permissive fiction writer in me, but I don’t care about any of that. I’m grateful to both Jackson and L’Engle for writing their strange fiction. I am no less grateful to them for sharing their stories of motherhood—whether they are fact or fiction or somewhere in between. Jackson’s husband, the literary critic Stanley Hyman (who does seem to have had some redeeming qualities), wrote after her death, “Shirley Jackson wrote in a variety of forms and styles because she was, like everyone else, a complex human being, confronting the world in many different roles and moods.” Yes! Oh yes.