A City of One’s Own

The recent anniversary of the coup attempt in Turkey on July 15, 2016, has reminded me that I’ve been back in the United States for almost a year. My friends and I from my “Istanbul years” now divide our lives into before and after the coup attempt, and while my constant comparisons of New York and Istanbul have faded, the indelible imprint of my life in “the City” has not left the way I view the US’s literary center.

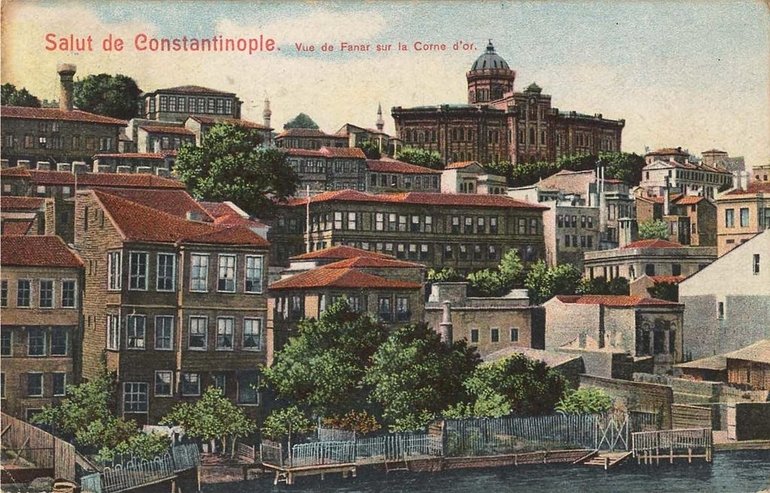

I’ve known Istanbul as “Η Πόλη” (Greek, pronounced ee POHlee), or “the City,” for as long as I can remember. In Turkish, it’s simply İstanbul, spoken with a sense of reverence and wonder. The current name of the city is said to come from the Greeks saying they were going to the City, or “εις την Πόλη” (ees teen POHlee), which then became “Ist-an-bul.” Like any İstanbullu snob, I think of “the City” as the urban center and not the sprawl of concrete that extends as far as Sabiha Gökçen Airport on the Asian side. I still think of Istanbul as a few districts, which include the Old City, Kadıköy, Beyoğlu, Beşiktaş, and sometimes, Üsküdar. The traditional bounds of the city ended around Şişli, which is now the second metro stop up from Taksim, and I still reflect on how at one point, the Byzantine walls of the city demarcated its end in the Old City. Perhaps in that way I’m not unlike native New Yorkers, who think of “the City” as just the island of Manhattan, whereas I, who grew up in New Jersey, mean all five boroughs when I say I’m going “into the City.”

New York has no singular poem that its inhabitants will recite on a whim, but every İstanbullu or adopted İstanbullu may start reciting the first lines of the poet Orhan Veli Kanık’s infamous poem “I Am Listening to Istanbul” unprompted, lines that go like this:

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed:

And the leaves on the trees

Softly sway;

Out there, far away,

The bells of water-carriers unceasingly ring;

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed.

While Kanık describes an Istanbul that is long gone, those who live in the city never seem to be able to resist the charm of the city as a legendary entity. Indeed, that’s what keeps places like Istanbul and New York going. Residents new and old experience a lived nostalgia, selectively recreating a past that in some ways was never there. We do this a lot as writers, as books like Goodbye to All That: Writers on Loving and Leaving New York, a collection of essays directly reacting to Joan Didion’s essay by the same title, attest. Writers look all so often toward potential, because that’s what our work is built on, the potential of dreams, the potential of a kernel of an idea that isn’t even a full story, but just that, an idea or a feeling.

Unfortunately potential isn’t enough to build a life. Istanbul and New York are built on dreams, but the New York I’ve come back to seems to delay those dreams when one has to get on by cobbling together multiple adjunct positions or with trying to find enough steady work at university writing centers when coupled with long commutes, as I’ve seen to be the case with writer friends here. The price of rents and real estate regularly shocks me, and I can’t see how this city, which relies so much on dream-making and on the reputation of being a creative hub, can be a dream-maker for anyone who does not have family money or support.

Istanbul is no easier. To be a creator there, even in 2009, required sacrifices and a full-time job to pay rent, or if one was lucky, parents to live with in the city. These days living and working as a writer in Istanbul requires a bravery that most American writers have never imagined they would have to muster, a bravery far beyond what it already takes to put pen to paper. The self-censorship that I remember being shocked by when I first moved to Istanbul in 2009 feels like nothing compared to the paranoia that undergirds a writer’s life there now under the very real post-coup threat of jail.

Yet I have a feeling that these two great cities will continue to engender belief in them as green lights. Even in their decline as affordable or safe literary centers, their reputation is enough to make one aspire to be a literary citizen among their parks and endless hills, their pigeons and seagulls, their street cafes and dark bars, their love affair with smoking and smoking zones, their merging of commerce with art. The dream of New York and Istanbul will carry on long after the heyday of those cities has faded, just as it always has.