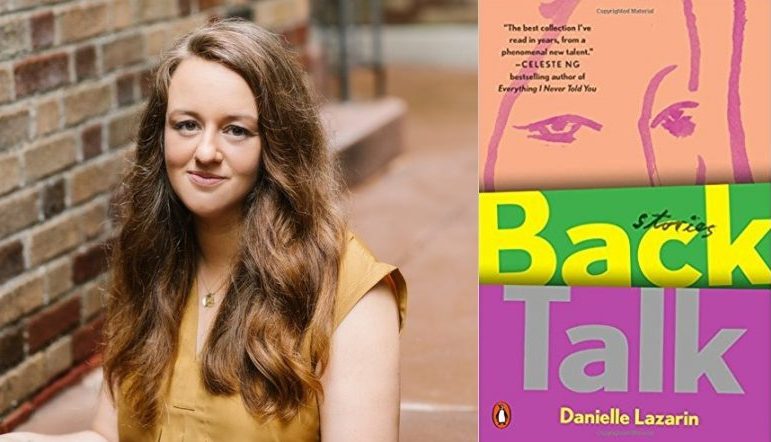

This is What Matters: A Conversation with Danielle Lazarin

I met Danielle Lazarin on Twitter, that entity that steals my time and dissolves my concentration even as it buoys me up with warm and intelligent companionship. I noticed her as a sharp, funny commentator on life as a woman, as a native New Yorker, as a writer, and I thought if she could sustain that voice in her fiction, then her forthcoming collection of short stories would be a glimmering jewel. Turns out she could, and it is.

I met Danielle Lazarin on Twitter, that entity that steals my time and dissolves my concentration even as it buoys me up with warm and intelligent companionship. I noticed her as a sharp, funny commentator on life as a woman, as a native New Yorker, as a writer, and I thought if she could sustain that voice in her fiction, then her forthcoming collection of short stories would be a glimmering jewel. Turns out she could, and it is.

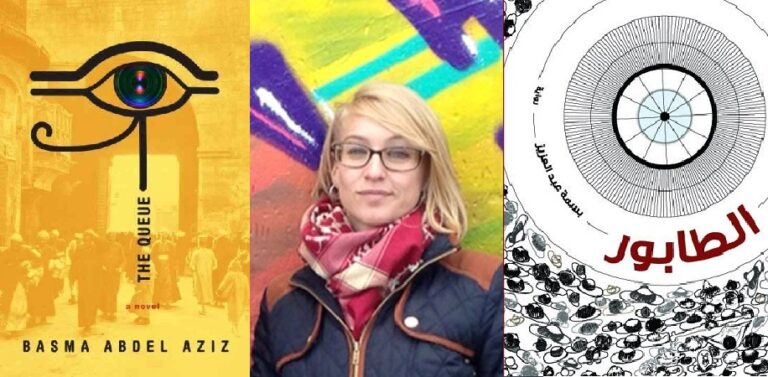

Her collection, Back Talk, made me think of Gina Berriault’s Women in Their Beds or Andre Dubus’s Dancing After Hours: work that acknowledges short stories as the star of the show and not just a warm-up act until the writer can put out a novel. Lazarin’s sixteen stories dip into women’s lives at various stages and they’re so realistic that at times I felt like she had eavesdropped on conversations I’d had with my girlfriends—from sophomore year of high school and from last week—swapping philosophies and clothing and working out ways to maneuver through a world that frequently throws up cruel and unnecessary hurdles in our paths.

Women face difficulties large and small in the world of Back Talk: A girl tries on a pair of her mother’s shoes to connect with her after her death. A woman gradually accepts her divorce by befriending the neighbor who buys her apartment. But among themselves they are safe, strong, protective and protected.

I reached Lazarin by phone shortly before the release of her collection, and we at last had a full, messy, human conversation, rather than the clever exchange of edited half-sentences we all engage in on social media. I was interrupting her mini writer’s retreat with two fellow-writers in Atlanta. We discussed how the wider world has always denigrated “women’s stories” as not important enough. How women’s stories have not been heard or believed since long before it became a daily theme in the newspaper, and how Lazarin eventually came to accept women’s lives as her material, well worthy of her time, attention, and care.

Cary Barbor: Many writers debut with a novel. Why did you choose short stories?

Danielle Lazarin: I was working on a novel which, ironically, grew out of a short story. I kept expanding and expanding it. But I became less interested in it. I made myself finish it and revise it. On the side, I kept having story ideas. And I just kept writing these stories to get them out of my head. This was all for myself—I didn’t have an agent yet.

For fun one day, I looked at how many stories I had, and saw that I had nearly enough for a collection. And I realized I needed to do the work that I wanted to do, and not what I thought would sell in some marketplace.

So I put the novel aside. I tried to revive it in many ways, but it just didn’t work. And that original story is not in the collection either.

CB: So would you say the short story is your natural form?

DL: I came up through creative writing programs, as an undergrad [at Oberlin] and then an M.F.A. [at Michigan]. And workshop mode is short story mode. That said, a lot of people in my M.F.A. program didn’t consider themselves naturally short story writers and were itching to write a novel, and I didn’t have that feeling. Every time I have an idea for a novel I get mildly nauseous. It terrifies me.

CB: In a short story, a writer has to do so much with so little. You are so adept at dropping a detail or two that tells a whole character or situation. Did it take you many revisions to get there?

DL: Once I knew that I was working on a collection and stopped pretending I was working on something else, my stories tended to come out more fully formed, closer to what they would be in the end. Which is not to say that they didn’t have a lot of work put into them. That’s the backlog of all those years I spent working. But in terms of pure craft, some things are just easier. It’s easier for me to pick a voice, for example, and know that’s it’s the right voice.

The other thing about a collection is, if you’ve published in a lot of lit mags, you’ve gone through your own rigorous editing process and if you’re lucky, you have great editors at the magazines. So by the time it’s in a collection, it doesn’t need as much revision.

CB: The collection is called Back Talk and so much of it is about women expressing themselves in one way or another. Was that something you set out to write about?

DL: I spent so long writing stories that were called “domestic,” which quite frankly I used to take as an insult. Now I’m annoyed at my former self for taking it as an insult. There’s a belittling of women’s stories that happens. Not only in the larger culture, but within workshops too. And I will say, I had a wonderful time both in my Oberlin workshops and Michigan. But the way people assume a story isn’t big enough, it isn’t worth enough, it isn’t examining the big questions—that started to get under my skin. I stepped back to look at the stories I was writing and saw that those stories are really important to me. And I was holding back on them. And I asked myself why. This is my material; this is what matters. So by the time the collection came together I knew that was a question I wanted to write into.

CB: I read your collection at a time when so many stories are pouring out in the news about abuse and exploitation of women. And many of your characters are refreshing because they don’t live to please others, as so many women are taught to do. Do these recent news stories make you think of any of your characters in the collection?

DL: So much of what has struck me in this larger conversation is about how women are supposedly responsible for these things that have befallen them. It has really made me nuts. In the title story, Back Talk, instead of speaking her story, the character just keeps it inside because she knows that what she says is not relevant to the story that’s already out there. And that she has no power in that. That character just knows that women’s stories aren’t believed. Unfortunately that does resonate with what’s going on in the news. The upside is that the more stories that get out there, the more women feel emboldened to tell their stories.

CB: This collection is refreshingly female-centered. I read that you submitted to journals with women editors only. What is your policy for submitting, and the thought behind it?

DL: Like many people, I was greatly affected by the VIDA count [an inventory of published work, showing that men account for two-thirds and women for just one-third]. It put such concrete numbers behind stuff that we all felt, that the voices in magazines and literature were male. Most of my grad school program was female; most of my readers are female. And I write stories about women. So it seemed like a simple thing to do. When I’m submitting, I look for places that have a female editor either as the editor-in-chief, fiction editor, and I think I did managing editor too.

And I did seek out a female agent. It’s been great to work with people who really respond to my stories on a level that’s also about identity. And people who know how to market my book because they share some of the experiences.