Achilles and the Art of the Character Flaw

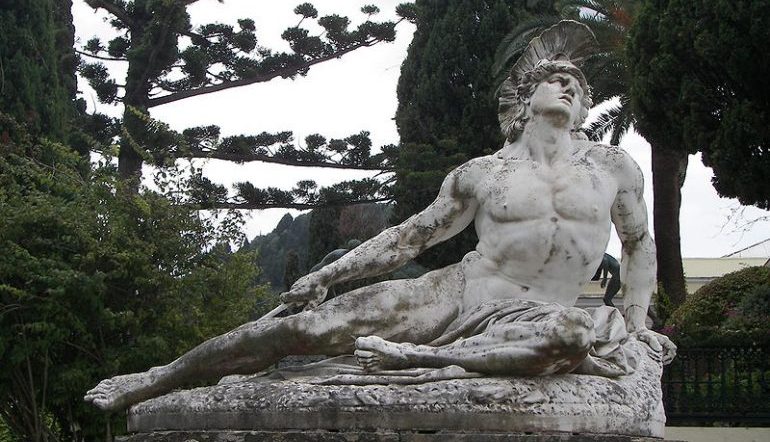

In the story of the Trojan War, Achilles’s “fatal flaw” changes drastically depending on the version and interpretation. Sometimes it’s his heel, the single weakness on an otherwise indestructible body; sometimes it’s his hubris, the crime of pride; sometimes it seems to be something more than either of those. In Madeline Miller’s 2012 novel The Song of Achilles, pride is just one piece of a larger emotional puzzle.

One of the most well-known aspects of Achilles’s story—that his mother dipped him in the River Styx holding him by the heel, making him invulnerable everywhere but that spot—doesn’t actually appear in Homer’s Iliad. It likely wasn’t part of the original oral tradition either; it doesn’t appear in extant poetry or art until Statius’s unfinished Achilleid around 95 CE. For scale, Homer’s epics are thought to have been first written down in some form by the 8th–6th century BCE, and the (possible) historical war would have been closer to the 12th century BCE.

Madeline Miller omits the “Achilles’s heel” storyline in The Song of Achilles; his supposed “invincibility” is just his excellent skill in battle, and his flawed nature as an individual manifests itself in much more complex ways. In the “Author Q&A” printed at the book’s end, Miller speaks to this choice in terms of needing narrative realism even in a story that often centers the unreal:

Some of the [myths about Achilles] I cut were actually quite well-known stories—like Achilles’ vulnerable heel. For some reason (and I know this sounds silly, given that there is a centaur in my novel), I have always found that story very unrealistic. After all, who dies from being shot in the heel? And it’s not a story that’s in Homer; it was added later.

This structural choice for The Song of Achilles is more than a “return” to the older story from Homer, which centers the fatal flaw of hubris. Miller reimagines a figure of Achilles whose pride is just one factor in the choices that he makes, alongside other complicated human problems, like his love for Patroclus, his relationship with his mother, and his fear of mortality.

The novel is told from the humanizing perspective of Achilles’s lover Patroclus. This perspective lends the reader an intimate, yet realistically incomplete, portrait of Achilles’s reasons for his major choices in the narrative: to go to war when a prophecy says that he would die young if he went, to refuse to fight in the tenth year when Agamemnon dishonors him, and to kill Hector even with the knowledge that his own death is prophesied to follow.

What does it mean for a story to be “character driven”? How can stories adjust to different ways of thinking about human agency? Miller centers Achilles’s relationships as dramatic catalysts much more than the prophecies themselves, making him more of a human and less of a pawn in the grand movements of fate. While the exclusion of Achilles’s vulnerable heel might seem like a minor detail, the emotional vulnerability that emerges from his closeness with Patroclus makes him more engaging as a character who pushes the story forward. He wants to protect his lover and live up to his immortal mother’s expectations; he’s doing his best to navigate the options available to him.

The various Trojan War narratives generally reflect a worldview from antiquity where the cosmic hand of fate does more for the stories’ movement than individual human relationships do. Modern audiences lean more toward seeing the world as populated by individuals making our own choices, and it makes sense that our stories would reflect that shift. By thinking about character flaws complexly, we can interrogate the vulnerabilities of a person like Achilles with much more depth and, perhaps more importantly, with a sense of empathy.