Hearing Voices: Women Versing Life presents Phillis Wheatley

Now you’re on an auction block, struggling to stand, naked except for a scrap of blanket wrapped around your shoulders. You watch as money exchanges hands and realize that you are owned now, someone’s belonging. These new people call you Phillis, again and again, as if the name your parents gave you is easily discarded, as if the old you does not exist. And when you learn the word namesake, understand that you are named for the slave ship that carried you farther and farther from your family, named after the staggering prison where you nearly died, wanted to die, do you lay down your head in despair? Or do you become a poet?

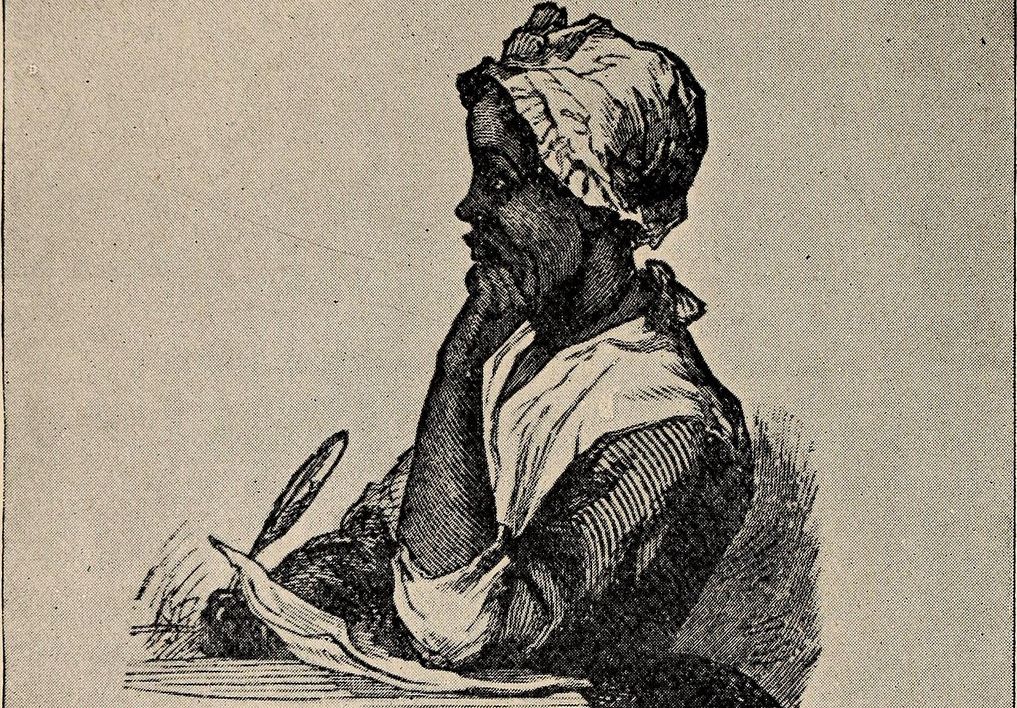

Phillis Wheatley not only became a poet, she became the first African-American poet to publish a full-length book of poetry. There tidbits of information about Wheatley that you might find, with slight variations, at any number of web sites: She was a slave for the Wheatley family in Boston, Massachusetts, during the Revolutionary war. The women in the family taught her how to read and write, but Wheatley fell in love with the works of Alexander Pope and began writing poetry on her bedroom walls at a very young age, and her first poem, “On Messrs Hussey and Coffin,” about the drowning of two sailors, was published in a local newspaper when she was about fourteen years old.

. . . Did haughty Eolus with Contempt look down

With aspect windy, and a study’d Frown?

Regard them not;–the Great Supreme, the Wise,

Intends for something hidden from our eyes . . .

However, there are some things I cannot tell you about Wheatley because no one knows: Her true name, for example, her country of origin, the date of her birth, her age— biographers assume she was six or seven when she arrived in Boston because of her missing front teeth— and I cannot tell you how she truly felt about being named after a slave ship.

As a slave poet, Wheatley must have balanced her verse while treading a fine tightrope of subjugation, and her poetry attends to subjects that would not offend those in power: Elegies, Christianity, and patriotism for the most part. Some believed that Wheatley expressed her true feelings through metaphor.

Vincent Caretta, editor of Phillis Wheatley: Complete Writings, suggests that one of Wheatley’s most well-known poems, “A Farewel to America,” hints at Wheatley’s hope to gain freedom while visiting England, where shipping slaves was illegal:

ADIEU, New-England’s smiling meads,

Adieu, the flow’ry plain:

I leave thine op’ning charms, O spring,

And tempt the roaring main.

Wheatley was taken to England to improve her health and to oversee the publishing of her first book, Poems on Various Subjects Religious and Moral, which she was unable to publish in the states (It was finally published in the states two years after her death.) She was granted her freedom upon her return from England in 1773, twelve years after she was sold on the auction block.

The Wheatley family perished one by one and left nothing to Phillis Wheatley, perhaps because she was a favorite of the female Wheatleys whom had few rights of their own. Wheatley married, had three children, and kept writing, despite having little success with publishing and her descent further and further into poverty.

In December of 1784, Wheatley’s husband was likely in debtor’s prison, two of her children were dead, and the third was dying along side Wheatley in the boarding house where she worked. On December 8th, mother and daughter were buried together in an unmarked grave, and the second manuscript Wheatley tried desperately to publish was never seen again.

There’s a statue of Wheatley in Boston and several organizations and buildings across the country are named in honor of her, but I think it’s long since time for a national tribute to a woman who wrote prolifically in favor of freedom from British rule and whose work was cited time and again in arguments against slavery, and who came to such a neglected and tragic end. Maybe what’s needed to honor Wheatley is a national organization that promotes reading and writing (including poetry, of course) in underserved communities. Still, it seems wrong to name anything, anyone after a slave ship. Instead, perhaps it should be called, “The Literacy Liberation Center.”

For now, I’ll honor Wheatley by recommending three great reads: Phillis Wheatley: Complete Writings, edited by Vincent Caretta; The Vintage Book of African American Poetry: 200 Years of Vision, Struggle, Power, Beauty, and Triumph from 50 Outstanding Poets, edited by Michael S. Harper and Anthony Walton; and The Garden Thrives: Twentieth-Century African-American Poetry, edited by Clarence Major.