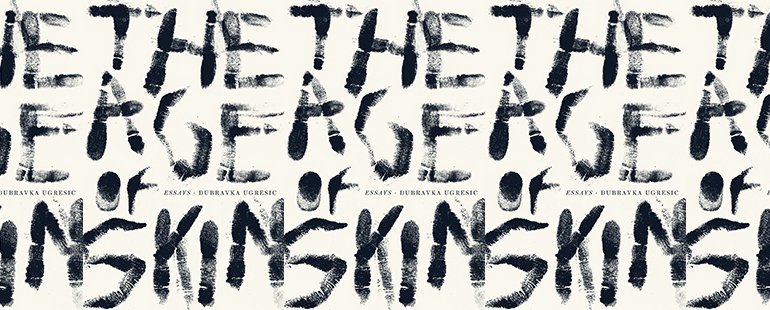

The Age of Skin by Dubravka Ugrešić

The Age of Skin

Dubravka Ugrešić

Open Letter | November 17, 2020

Dubravka Ugrešić’s newest collection of essays, The Age of Skin (translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursać), opens with fire. “I shudder when I hear the hackneyed (and strident) line that life writes novels. Let’s be clear: if life wrote novels, there’d be no such thing as fiction.” She goes on to lambaste the self-destructive literary establishment, calling out specifically “the avaricious publishers, laggardly editors, wishy-washy critics, unambitious readers, and authors lacking in talent but greedy for fame.” It’s a nervy beginning. From here she moves to the English language metaphors of skin, then to a survey of the varieties of skin—from Eastern European love for leather jackets and shoes, the embalming of Lenin, tattoos, the weight and mass of human flesh, pop culture’s appetite for zombie stories——before ending with an image of the twenty-first century as a purpled, stained, oozing corpse. “The Age of Skin” is discursive, only just held together by the energy of Ugrešić’s singular voice, and it’s a wonderful introduction to the sixteen essays that follow.

Ugrešić made her debut in English with an assemblage of columns written in the early 1990s, when, as a visiting scholar in the U.S., she was commissioned to write about her impressions of American life for a newspaper in Amsterdam; she accepted the visiting professor position to escape the escalating tensions in her home city Zagreb. With the knowledge of the Yugoslav Wars raging at home, she confronted frivolous American consumerism, the beauty of North America’s vast landscapes, and people who were little aware of what was happening in Europe. Soon after the publication of these pieces, her anti-nationalist and anti-war views made her a target in Croatia (she was proclaimed “a witch”) and she was forced into exile in 1993. With Age of Skin, she continues in the spirit of that early work, eager to reveal the ways in which the individual and the ordinary moment is never spared from the larger, unyielding forces of misogyny, fascism, communism, and capitalism.

“Why am I bugging my reader and describing at such length this entirely unremarkable and uninteresting episode of daily Amsterdam life?” she asks in “Zelenko and His Missus”, an essay about a shop selling products from the former Yugoslavia, a place of national pride for the Croatians, Bosnians, Serbians, and Macedonians living in Amsterdam. Finally making her way to the Eastern outskirts of the city to the famed warehouse-grocer, even nostalgia-wary Ugrešić feels the appeal of those products from her youth, like the “chocolate-covered Domaćicia cookies” that “used to melt so yummily on the sunny Adriatic beaches.” But Zelenko and his missus are rude shopkeepers; they’re upset that Ugrešić and her friend have interrupted their breakfast, that they dare ask about the cost of the unpriced goods. So frustrated by how they’ve been treated, Ugrešić and her friend walk out without purchasing anything. This small incident, this “unremarkable episode” at Zelenko’s, according to Ugrešić, serves as a perfect example of the strained “relationship between the individual and government, between citizens and their states of Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Macedonia” and “marital, friendship-based, business, familial and every other kind of relationship.” Even so, the unwavering loyalty of the customers of “Zelenko-land” surprises Ugrešić. Their desire to claim Zelenko’s as their own is so powerful that they’re willing to ignore Zelenko and his wife’s cruelty and their possibly illegal business.

Ugrešić’s own experience living in exile for the past thirty years (she has been based in Amsterdam since 1996) makes her keenly attuned to the power of the center, to the power of belonging—a space and force she identifies as male-dominated, sophophobic, pop culture obsessed, and consensus-driven. She’s profoundly interested in those like her who exist on the periphery—the intellectual, the immigrant, migrant, émigre—and the ways in which they contend with the gravitational pull of that space. Pop culture is part of that pull. Ugrešić’s essays, as a result, are filled with references to theater, books, films, television shows, theater, music videos, pop songs, anthems, soccer, museum exhibits, monuments, celebrity photographs, providing her with endless material to mine. In “La La People” she questions the unanimous love for the film La La Land. In “Artists and Murderers” she wonders why crooks have an easier path to publishing than literary writers. In “The Little Guys and the ‘Gypsy Fortune’” she meditates on a museum exhibit dedicated to the suicides brought on by the financial crisis.

In “There’s Nothing Here!”, however, Ugrešić returns to the land of the former Yugoslavia, visiting spas and hot springs in Serbia and Croatia. During one of these spa weekends, she travels to the Petrova Hills to see a famous war monument by Vojin Bakić, only to find it in ruins. While driving back to the spa in a mournful silence, her niece calls; she wants to share with her aunt what she considers the most important day of the decade, the day of the wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle. The phone call is a devastating but poignant reminder of the ways in which even family members can inhabit completely different realities. Ugrešić wonders, “who in the world cares about a monument that’s been destroyed, no matter how breathtaking it may have been as a work of art, and who am I to take this on and call out others for failing to maintain it?” It’s a moving moment by a writer who spends most of her time looking outward, wading through “ubiquitous popular culture.”

It’s also a moment that points to Ugrešić’s astonishing tonal range. As relentlessly critical as she can be, she is also tender, endlessly curious, and enjoys the company of others. It’s this rare blend of polemicism and heart that makes Ugrešić such a joy to read. Combined with the fact that she’s wickedly funny. After the incident at Zelenko’s, she dedicates a full paragraph to an imagined scene of Zelenko and his wife, giddy with the power they have in humiliating others, fornicating in the corner of the warehouse, “among the canned beans and smoked pork tenderloin, world’s finest.” Her occasionally lurid daydreams often arrive without warning, but are a welcome swerve. It’s a great credit to Ellen Elias-Bursać’s nimble translation that the transitions between analytical, philosophical, colloquial, and comedic are swift and easy to follow.

In The Age of Skin, Ugrešić ruthlessly deconstructs modern life, exposing its basest self, and it’s this vision, her insistence on tearing down façades, on seeing through the innocuous, the outwardly innocent, that has made Ugrešić a formidable cultural critic. She demands that we see deeper, even where we refuse to look.