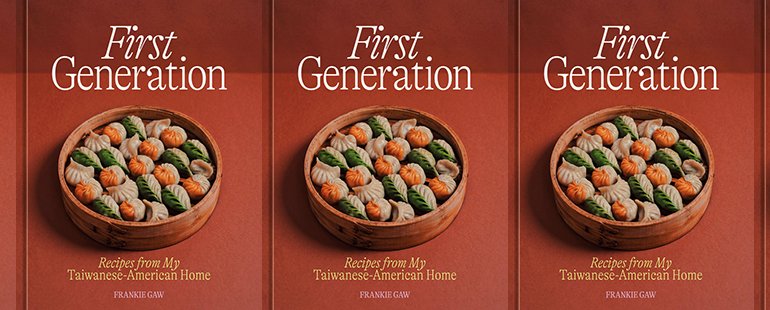

Food and Identity in First Generation: Recipes from My Taiwanese-American Home

Though Frankie Gaw’s debut book First Generation: Recipes from My Taiwanese-American Home (2022) is ostensibly a cookbook, it’s also an archive of the Taiwanese American experience and an earnest exploration of the many facets of the author’s identity as the queer child of Taiwanese immigrants. The book is divided into seven sections—An American Pantry, Small Eats, Bing, Noodles and Rice, Dumplings and Bao, Family Style, and Bake Sale—each of which open with a narrative anecdote followed by several recipes. Most of the recipes are also introduced with paragraph-long stories that relay how the recipe came to be. These stories speak to Gaw’s childhood memories growing up with his grandmothers’ cooking and watching his parents adapt to life in the US, and they also provide insight into Gaw’s identity as a Taiwanese American—a feeling of “in-between” and of duplicity in being both Asian and American while simultaneously failing to be enough of either.

To understand Gaw’s food is to understand Gaw. He opens the book with a dedication to his parents, to the Asian community, and to the LGBTQ+ community; to understand him and his food is to start by understanding his upbringing. Gaw’s parents emigrated from Taipei, Taiwan, to Cincinnati, OH, in 1985. As a result, Gaw grew up between food cultures, enjoying both the spoils of a working-class family in the Midwest, where Olive Garden was considered a treat, as well as Taiwanese food prepared by his maternal grandmother, who lived with them throughout much of his childhood. “I can still get excited over a bologna sandwich, fight a stranger over the merits of Olive Garden’s breadsticks, and have heart palpitations seeing the green 59A exit sign toward Cracker Barrel and dreaming of their buttered cornbread,” Gaw writes. “And yet, I still get harassed to ‘go back to my country’ and ridiculed for my jet-black hair and tan skin. So where do I belong?”

This desire for belonging shines through in both Gaw’s writing and his food. He speaks about his nuclear family’s attempts at assimilation as a means of survival—he sensed growing up that his parents adopted whiteness as the cultural ideal, turning to Olive Garden for food inspiration rather than the recipes and food traditions that they had left in Taiwan. He shares that his mom helped him to “out-Gusher and out-Dorito every white kid in the competitive sport that is the school lunch.” It was only when Gaw’s maternal grandmother moved in with the family that he began to taste and appreciate Taiwanese food with regularity. As an adult, he began learning to cook, cooking alongside both of his grandmothers to learn the foundational skills of Taiwanese cuisine. Having built that foundation, Gaw then experimented with the flavors and ingredients, creating a food niche that not only spoke to a nostalgic Midwestern upbringing but that also embodied the “in-between.”

Gaw’s food mirrors his complex identity, with recipes that are equally grounded in Taiwanese cuisine and in American nostalgia. He describes his recipes, and in particular his dumplings, as a “conversation across traditions and cultures.”While there are classic Taiwanese eats, like popcorn chicken, fan tuan rice balls, dan bing, lu rou fan, and more—inclusions that speak to his pride for his Taiwanese heritage—it’s the fusion recipes—Cinnamon Toast Crunch Butter Mochi, Lap Cheong Corn Dogs, Stir-Fried Rice Cake Bolognese, Lion Head Big Macs—that really speak to his ability to hold his Asian and American identities simultaneously.

First Generation is not only a celebration of the first-generation Asian American experience but also a proclamation of the uniqueness of the Taiwanese American diaspora, a nuance that often gets lost in the embroiled politics of cross-strait relations. Throughout the book, Gaw often speaks generally to the children of first-generation East Asian immigrants, such as in his inclusion of an “Asian Market Snacks” photo spread, which features iconic Asian American goodies, such as Oishi Shrimp Chips, White Rabbit Candy, Yakult, and more. He is also specific, though, in his identity as a Taiwanese American in an age in which Taiwanese and Chinese identity are often conflated. As recently as 2021, even PEW Research conflated the two, inadvertently erasing the identities of hundreds of thousands of self-identifying Taiwanese Americans. It is important, then, that Gaw proudly asserts his Taiwanese identity and uplifts uniquely Taiwanese food traditions and products, such as Beef Noodle Soup, Formosa Brand Pork Floss, Apple Sidra, and more.

Gaw also subverts the stereotypical lunchbox story shared by many immigrants and children of immigrants. His descriptions of Taiwanese ingredients and dishes are fused with pride and joyful memories of his father and two grandmothers. Rather than experiencing shame in his Taiwanese heritage, there is instead a sense of Gaw overcoming shame in his love for foods demonized by the white American consciousness, and in his love for carbs and processed foods and spreadable cheese. Gaw combines childhood memories of these demonized foods with traditional Taiwanese recipes as a means of insisting that it is important to be proud of your food traditions and the memories that food evokes.

In “Coming Out,” a letter written to his late father, who had passed away seven years earlier from lung cancer, included in part three—“Bing”—Gaw both reminisces on the ability of food to evoke memory and also muses on what it would be like to have had the opportunity to come out to his father. In cooking the foods that he once enjoyed eating with his father, he is able to continue an imagined conversation, sharing with his father both the joys and successes as well as the messiness and grief that he has experienced in the years since his death. Through the letter, Gaw reflects on who he has become in the time after his father’s passing, expressing hope that his father would have understood his sexuality and would have bonded with Gaw’s boyfriend. Gaw also reflects on the ways he continues to define himself through the lens of his father. He writes that he “inherited [his father’s] ability to avoid vulnerability throughout a lifetime,” a reflection that makes publishing a book on grief and the messiness of identity politics daunting. The letter concludes with a sense of hope—a recognition that while grief never truly resolves itself, life can instead become “a juxtaposition of happiness and sadness all scribbled together in the same messy drawing.” While Gaw’s father will always still inform Gaw’s goals, hopes, dreams, and cooking, Gaw is also ready to find out who he is beyond the identity of “[his] father’s son.”

Gaw introduces part six, “Family Style,” with a short narrative titled “Dinners with Antoni Porowski.” This story—which begins, “God, in the form of a shirtless Antoni Porowski from Queer Eye, asks me, ‘When are you most happy?’”—shines as an exploration of Gaw’s intimate relationship with food and an understanding of the generations that preceded him. As Gaw contemplates Antoni’s question, he is transported to three dinners, each of which features a whole steamed fish, an iconic component of many Taiwanese family dinners. With speculative elements and bent time, Gaw shows us first his own dinner with his extended family, then his mother eating dinner while doing homework as a student under the watchful eye of his grandmother, and finally his grandmother eating dinner as a young child, or more accurately picking at the scraps that remained, an activity that Gaw imagines led to her love for fish cheeks and eyes. This imagining of the dinners that came before him allows Gaw to recognize the abundance of his own childhood and to remember the resilience of the generations who made that abundance possible.

First Generation is a cookbook, but it is also a meditation on identity and comfort in your own skin. In writing First Generation, Gaw claims his space. “Food has been at the heart of my discovering both deep shame and overflowing pride,” he writes. In sharing his food and writing, Gaw has given us an intimate look into his Taiwanese American home.