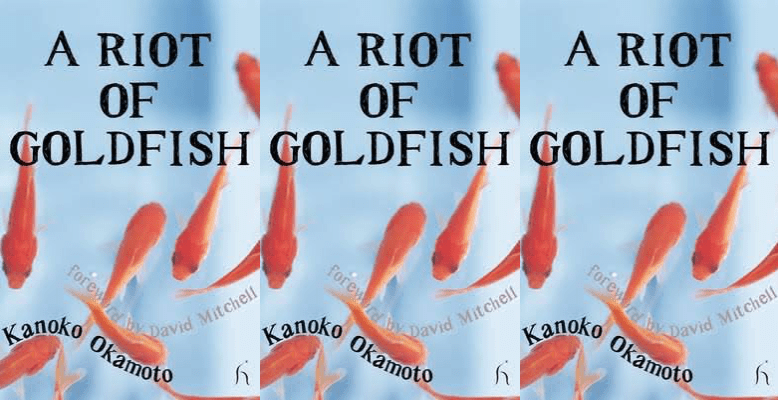

A Riot of Goldfish

A Riot of Goldfish

Kanoko Okamoto (Translated by J. Keith Vincent)

Hesperus Worldwide, January 2011

114 pages

$15.95

David Mitchell, in his fine introduction to this slim volume of two novellas, writes that author Kanoko Okamoto’s great theme is the “frustrated striving for aesthetic perfection.” Certainly her novellas have that quality, something like Hawthorne’s tales of obsession—particularly “The Birthmark” and “The Artist of the Beautiful”—but they gain an additional interest, at least for the non-Japanese reader, by dealing with unfamiliar and fascinating art forms: goldfish breeding in “A Riot of Goldfish” and Japanese cuisine in “The Food Demon.”

In “A Riot of Goldfish,” the better of the two, Mataichi becomes fixated on Masako, the beautiful daughter of a rich man. His fascination is partially based on Masako’s “lack of personality”; he describes her as a kind of “mechanical doll that spoke through a special talking apparatus.” Her strange, distant beauty becomes linked to the increasingly elaborate goldfish that Mataichi breeds in school, so that when it becomes clear Masako is unattainable, Mataichi becomes obsessed with recreating Masako’s loveliness through that peculiar medium.

Okamoto describes how different breeds are combined to create these living sculptures: “The fins should envelop the body as they swayed, like the gown of a goddess; the body should glisten with a myriad of freshly painted colours, and most important, it should be spangled with black dots at coquettish intervals, like the bolero jacket of a Spanish dancer.”

Okamoto writes in a beautiful and sometimes elaborate style, but she also clearly knows about goldfish, and her prose often combines poetry and biology: “When the flowering season arrived in the following year, the breeding stars along the males’ pectoral fins opened their moistened eyes like the evening sky in spring, thus announcing the beginning of the mating season.” If you find this kind of stuff fascinating—as I do—these novellas are for you.

Like Hawthorne’s characters, Mataichi basically destroys his life in the quest for the ideal goldfish, but by a strange and circuitous route he does achieve the perfection that he seeks and the novella becomes, by the end, a wonderful parable about the artistic process.

(“The Food Demon,” the second novella in the volume, features a chef named Besshiro attempting to climb the social ladder of pre-War Japan. This story is a bit meandering, but it has lovely descriptions of food and the hybrid culture created when Japan first began to Westernize.)

It is nice, after half a century, to finally have Okamoto’s work available in English. (Okamoto herself died in 1939.) Anyone interested in these distinctive Japanese art forms, or in an exploration of the artistic temperament—which seems to be similar whether one works in words, food, or goldfish—should definitely search it out.