A True Fable

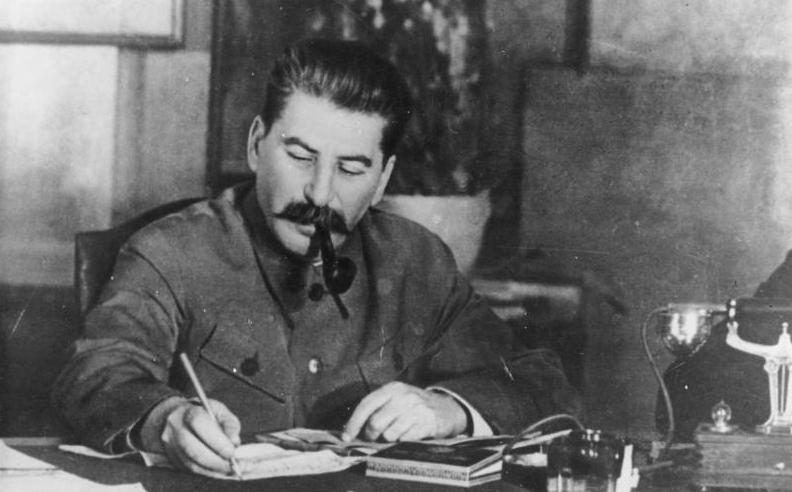

“The orders were given from Stalin’s country house at Kunstevo” begins Nathan’s Englander’s perfect short story “The Twenty-seventh Man.” In it, Englander uses a combination of the horror of history and the beauty of fable to tell a story about the power of story itself.

The story, about Stalin’s purge of any Jewish writers in Russia, begins with bare-bones language about the signing of the order to arrest and execute twenty-six writers (and an accidentally included twenty-seventh). It then goes on to tell the details of the more problematic arrests. This builds a pattern in the story, leading up to the arrest of the twenty-seventh man, Pinchas. Pinchas is a writer, but not a literary giant like the other twenty-six; rather, he has never been published. His words and stories are only for himself. Here is where a hint of magic slips into the piece: the mystery of how and why Pinchas’s name ends up on the list of those to be executed.

The story couples the disturbing real elements of history—the brutal arrests, the impending executions—with the conceit of oral storytelling. Pinchas recites the story he is working on to himself over and over. This story within the story is about a man who wakes to find that he has died. In other hands, this might be too obvious of a metaphor, but Englander’s skill is shown in the strange elegance of the fable-istic tale and its place within the greater narrative. “The morning that Mendel Muskatev awoke to find his desk was gone, his room was gone, and the sun was gone, he assumed he had died” is the opening of Pinchas’s tale, and it darkly mirrors the opening of the greater story, where Stalin signs the execution papers one morning at his own, unvanished, home.

As the writers inside their cell get to know one another, they come to accept Pinchas into their midst even though he is an uncelebrated, unpublished writer. One of Englander’s most beautiful sentiments here might be the idea that if you write than you are a writer. There are no boundaries between story-tellers, no systems that should keep them apart.

And going with this, the kindness of these writers accepting Pinchas is balanced against the banal cruelty of the guards who come to assemble the twenty-seven outside and execute them. All of these things can exist within the same continuum, which is what makes them even more beautiful or even more horrific.

At the end, the story coalesces (as it inevitably must) with the full oral-telling of Pinchas’s fable, which is, one of the writers states: “like a shooting star. A tale to be extinguished along with the teller.” And here, again, is where a hint of magic comes into play, because of course the tale hasn’t been extinguished—it passes on to the readers. It might be a fable within a fable, but it’s one surrounded by the evil of history. But what survives aren’t the names of the executioners but rather the words of the lost. Story, Englander argues, is sometimes all we have, and this is one of the things that makes it so powerful.