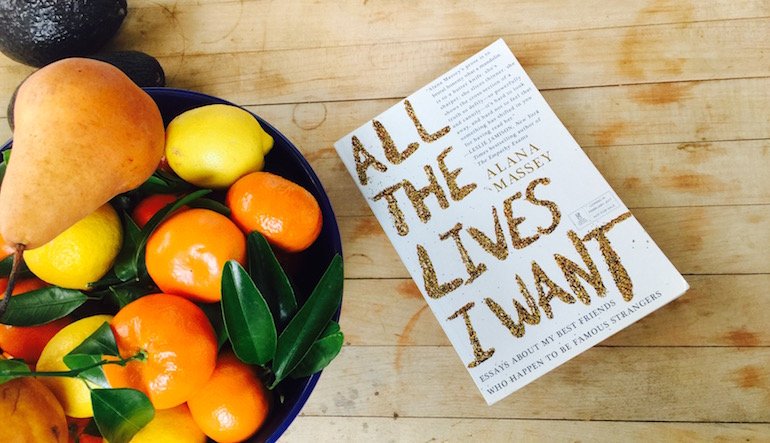

All the Lives I Marched For: Alana Massey’s Second Stories

A few years ago, one of my students wrote a story about college girls slowly trying to go crazy in honor of their idol, Sylvia Plath. The class, like the supporting characters in the story, speculated, diagnosed, and condemned them for glamorizing mental illness. As readers, we were outsiders and spectators of their secret sorrow, which just enraged some of us all the more, and made the writing even better. The untold stories behind private, invisible pain enabled a class of hungry undergraduates to pick that pain apart—to decipher its cause, or whether or not it was legitimate. Naturally, we decided it was; pain is legitimate whether or not we understand it. And while the college girls in the story did not follow Plath to their graves, they were part of an established cult that values the authenticity of her depression perhaps even more than her writing. Those girls in the story, and the followers of Plath in real life, perform depression to express depression.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie gave a TED Talk about the dangers of a single story, a story told by a privileged class who often craft incorrect and stereotypical narratives about others. As a culture, we have become better about asking for second and third stories—the ones that complicate an easy stereotype or bring a new reality to public attention—although we have so far to go. This second story, the one that would be told by a silenced or private voice, like the girl-fans of Sylvia Plath, is the one Alana Massey teases to the surface of her essay collection All the Lives I Want, out this month from Grand Central Publishing. Massey blends pop culture figures with fictional women and real writers to decipher the lessons and legacies famous women leave behind, and how we understand and redefine experience and ourselves when we look beyond the surface story.

One of my favorite essays in Massey’s debut collection is the titular “All the Lives I Want,” about those countless young women who take to the internet with Sylvia Plath quotes and images, alongside their own selfies and quotidian documentation of their self-involvement. “The ongoing act of self-documentation,” writes Massey, “in a world that punishes female experience (that doesn’t aspire to maleness) is a radical declaration that women are within our rights to contribute to the story of what is means to be a human.” Sylvia Plath is a mere catalyst for bookish young girls to elevate their own experience to an art form, and by devoting an entire essay to this, Massey gives a useful reminder that dismissal of self-expression by the young, the depressed, and the female, comes from a dangerous and privileged vantage point.

Massey most often lends her acute cultural criticism to pop culture—both its fictional portrayals and its celebrity cornerstones. In her opening essay, which originally appeared in Buzzfeed Reader in 2015, I learned I am a Winona in a world made for Gwyneths. From the onset, Massey probes how society shapes or punishes women based on how we talk about or dismiss them. Of Winona Ryder and Gwyneth Paltrow, she says, “One lives a messy but somehow more authentic life that is at once exciting and a little bit sad. The other appears to have a life so sufficiently figured out as to be both enviable and mundane.” There are, she intimates, third and fourth and fifth stories even lurking within the riven contours of second stories.

This made me wonder whether all women think they’re Winonas—whether we all see ourselves as misfits—and whether the story we believe about ourselves and other women around us is that the world is not made to support us if we keep trying and getting it wrong while other women seem to breeze through. Massey’s project examines several scorned and ridiculed women: Courtney Love, for stealing her dead husband’s music, as though she couldn’t have written it herself. Or the notorious Lorena Bobbit, whose husband repeatedly raped her, and who cut off his weapon to protect herself. Massey writes with as much empathy about the women we mock as she does the women we admire, like Anjelica Huston, Joan Didion, and other queens of cool.

Each essay takes its time dismantling the story we hear and telling the other side of it to create a new understanding. On the manufactured beef between Lil’ Kim and Nicki Minaj, Massey exposes our appetite for women in direct competition with one another, and how the media serves up exactly what we crave. When we hear the story of Mel Gibson’s public meltdown at the hands of his ex-wife, who secretly recorded his abuse, Massey surmises that recording an anti-Semitic tirade is the only recourse the wife feels she has against a powerful and well-lawyered tycoon. When Kanye West says he wanted to take “thirty showers” after breaking up with Amber Rose, Massey focuses on Rose’s subsequent activism, arranging a “Slut Walk” to bring attention to society letting West, and millions of other men, get away with blaming women for their own gendered mistreatment and abuse. Women stay silent or speak up as a means of survival, their quiet, secondary stories showing their complexity and necessity.

Massey’s collection could not have come at a better time. Unsurprisingly, as I joined three quarters of a million marchers in Los Angeles the day after the inauguration, I thought of all the women I marched for. Marching for lots of people means marching for lots of issues, lots of stories, and all of the teeming humanity that makes America a diverse, rich, and cultural land. Massey shows that telling the story behind the story is our greatest tool in unity. We must follow her lead and insist on more complex stories, on hearing silenced voices, and on representing those it is easiest to condemn. This is a good angel of literature in a time when culture is threatened. This is empathy as resistance. This is what will save us—our kindness our greatest weapon in revolution.