The Making of a Poetry Reader

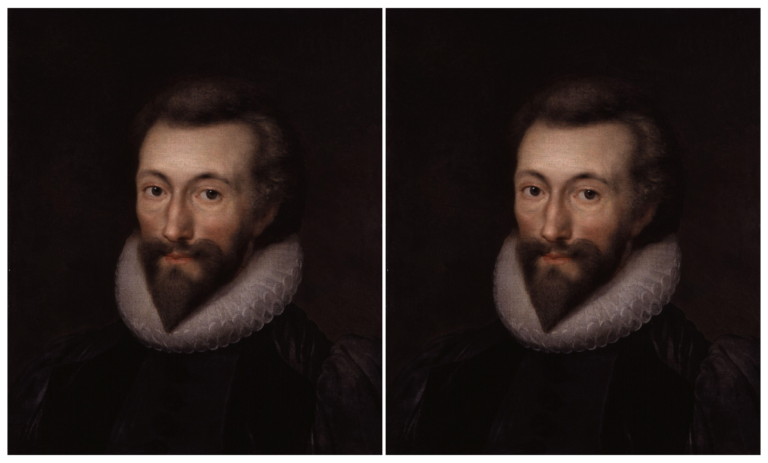

Reading John Donne’s “Air and Angels,” I came to know that if I listened to a poem, I would know it, even if I didn’t understand everything it said.

Please note that orders placed between February 1-February 17 will not be shipped until February 17. Thank you for your patience.

Reading John Donne’s “Air and Angels,” I came to know that if I listened to a poem, I would know it, even if I didn’t understand everything it said.

As a student poet, I never once read a book of poetry I knew to be written by a bi+ poet, much less one who expressly addressed and celebrated a non-monosexual identity.

There’s no such thing as a singular “poetic tradition.” To suggest otherwise is horrendously erasive of the myriad poetic traditions, many of them oral, belonging to the world’s diverse cultures.

Poetry, Polish poet Wisława Szymborska contends, is the operative exercise of not knowing.

As poets and readers of poetry, we might ask ourselves how our poetry provides a kind of sanctuary from violence or else offers us a place to work through our fraught reactions to a world in which school shootings can happen.

The #MeToo Movement has opened up the public discussion around violence against women, especially sexual violence. In the last few years, many of our contemporary poets have written frankly and devastatingly about the many kinds of violences women disproportionately face.

How do we tell our stories? What form best fits the autobiographical? For many writers, working in one genre is not sufficient, or else a single genre does not exhaust a writer’s obsession with their subject matter.

The first literary interviews I remember reading were those conducted by my undergraduate poetry professor, a white man of a certain age. They were compiled in a collection published by a university press in 1983. White men were asking most of the questions, and white men were answering.

Telling has the function of establishing authority, what our rhetorician friends call ethos, especially when the first-person point of view functions as a witness to an event or atrocity.

No products in the cart.