On the Enduring Appeal of the Bildungsroman

Though genre forms and conventions have changed rapidly throughout the short history of the novel, the popularity of one subspecies has endured: the bildungsroman, or coming-of-age novel.

Though genre forms and conventions have changed rapidly throughout the short history of the novel, the popularity of one subspecies has endured: the bildungsroman, or coming-of-age novel.

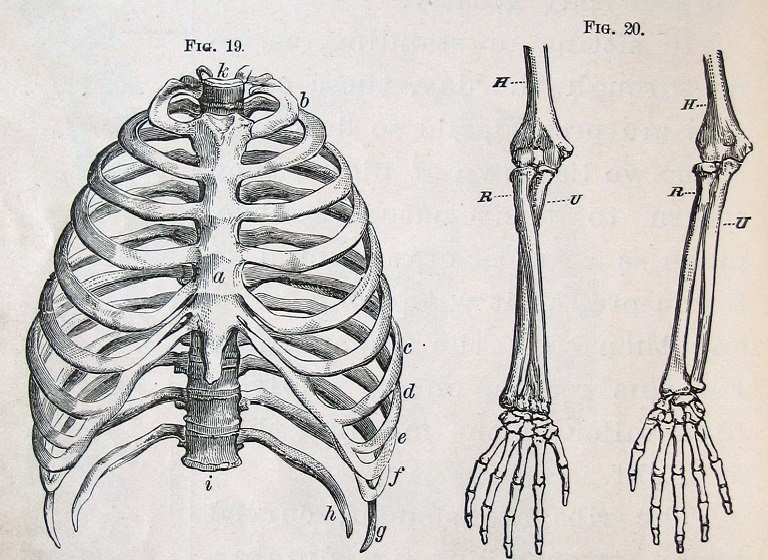

Doctors have been writers for as long as they have been doctors. The disciplinary divide between the humanities and sciences is a recent invention. Judging by the quantity and quality of writing by doctors in the past several decades alone, I might also suggest that some of our best philosophers have been physicians.

Several years back, I read a book that was unlike nearly any other I’d read before in one striking way: nothing particularly bad happened in it. The protagonist experienced minor internal struggles and dilemmas, but basically, everything came up roses. This felt like a major departure from Great Literature as I knew it…

From Odysseus’s faithful Argos to White Fang to Phyllis Reynolds Naylor’s Shiloh, dogs have occupied the centers and peripheries of human stories since we began telling them. It’s no wonder; dogs were first domesticated by hunter-gatherers (not, as many believe, by agriculturalists) over 15,000 years ago, the first species to live among and alongside people.

The postmodernists are often credited with originating the idea that all the world’s a text, a constellation of signs and symbols to be read and reread unto eternity. Really, it was the Jews. Judaism is a religion obsessed with text and textuality, with making meaning through the cultivation of relationship with the written word.

The reputation of the nineteenth century novel tends to precede its reading. By this I mean: few readers come to first contact with the likes of JANE EYRE, MIDDLEMARCH, or TESS without some established prejudice for or against the genre, usually in the milieu of a middle or high school literature class.

When my brother and I were kids, my parents would watch what we called “screensaver movies”: films that moved at a leisurely pace and boasted periods of little action in the traditional sense, featuring instead long, lingering shots of landscapes, interiors, characters’ expressions. We mocked and groused.

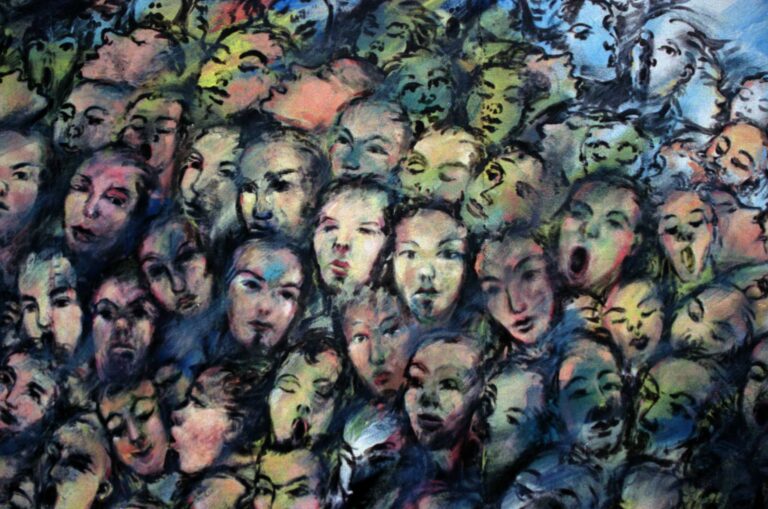

In a sense, madness (to use an archaic but attractive term) is a problem of narrative. To put it plainly: mental illness makes it difficult to know just what the heck is going on, or to what extent one’s perceptions of events can be trusted.

All literature is, in a sense, the literature of place—for all literature takes place someplace, calls up a setting with all its specificity of look, taste, sound. To ask the essential question of literature—How do we live?—is also necessarily to ask: Where do we live?

No products in the cart.