Big Picture, Small Picture: Context for Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon

This blog series, Big Picture, Small Picture, provides a contextual collage for a chosen piece of literature. The information here is culled from newspapers, newsreels, periodicals, and other primary sources from the date of the text’s original publication.

“Nobody, friends”—Polyphemus bellowed back from his cave—

“Nobody’s killing me now by fraud and not by force.”—Odyssey, Homer (translated by Robert Fagles)

Valentine’s day, Chicago, 1929. A group of Al Capone’s henchman, dressed as police officers, walk into rival mob boss Bugs Moran’s headquarters and gun down seven men, including the infamous Gusenberg brothers. When the real police arrive and question Frank Gusenberg, the bullet-riddled hitman’s whispered last words uphold the mafia’s code of silence: “Nobody shot me.”

One year later, on the west coast, residents of San Francisco open their windows and strut down the inclined avenues, enjoying the city’s second warmest February day in recorded history. To celebrate the lover’s holiday, they turn the radio on and dance to the latest hits, including Marion Harris’s sultry and crackling lament, “Nobody’s sweetheart.”

You’re nobody’s sweetheart now,

Cause nobody wants you somehow.

But the City by the Bay is troubled. A small man with a “wild look” haunts the streets, stinging women with a drug-laced, sharpened point. The “needle thug” has attacked two women already this week. In the East Bay, a suspect has been spotted, not for the first time, spreading tacks over a busy road. A burglar on the city’s west side makes off with two rugs from a private home, another steals $8.75 from an elderly couple’s sock drawer, and a peeping tom flees when a girl spots him at her window. “Someone in Berkeley is just about the meanest person in the world,” nine-year-old Marion Blackmore tearfully tells the police, after somebody absconds with her scooter.

Offering relief from the tide of crime in San Francisco, private detectives take out advertisements in the Chronicle. The Costello Detective Bureau boasts “secret service” agents that are willing to operate anywhere. Abbens Confidential Service claims to be “reliable, accurate, and bonded.” The Kane agency “charges moderately.”

Valentine’s Day, 1930. Dashiell Hammett’s genre-establishing detective novel The Maltese Falcon, set in San Francisco where the author lives, is published. Sam Spade, the hard-boiled sleuth protagonist, tries to unravel a knot of clues involving his murdered partner, a beautiful woman seeking protection, a wealthy collector-and-criminal, and a missing bird statuette. The bird, which serves as the Macguffin that propels the classic plot, is encrusted with priceless jewels, and thus has a long history of being stolen, recovered, and stolen again.

Such intrigue occurs not only on the pages of Hammett’s pulp detective novel. In May of 1930, the Ivy League satirists of Harvard’s Lampoon arrive to their newsroom to find their beloved copper ibis, the symbol of the newspaper since 1909, missing. As for suspects, “wrathful ‘Lampy’ editors promptly cast suspicion upon the Yale Record and the staff of the Harvard Crimson, with which they traditionally have strained relations.” The bird would be recovered and stolen many times over the next several decades. In 1953, snickering members of the Crimson would even present it to Russia’s deputy ambassador to the U.S. as a token of good faith. The retrieval of the ibis on this occasion proved particularly awkward.

In May of 1930, back in San Francisco, the desperate owner of Dixie, a Maltese Terrier with a studded collar and long, curly white hair, posts an ad in the paper when the dog wanders away from home. In October, the cause of the disappearance of a blind Maltese Kitten that answers to “Peggy” is speculated upon in a lost and found ad: “Strayed or Stolen. $5 reward.”

In September of 1933, the Maltese Falcon is again purloined, this time by a young British plagiarist named Cecil Henderson. Mr. Henderson is so enamored with the American detective novel that he transcribes it by hand himself and, “just for fun,” sends it to the Lincoln Williams publishing house, which releases the novel as Death in the Dark. The difference between the original and the fake? Hammett’s novel features two murders, and the counterfeit only has one.

Near the end of the novel, Spade recovers the falcon and learns that it is a worthless replica. The difference between the original and the fake? No jewels. Spade also learns that Brigid O’Shaughnessy is less damsel-in-distress than femme fatale. She pleads with Spade to let her go unpunished for her sins, professing that despite everything she’s done, she loves him. Doesn’t that count for something?

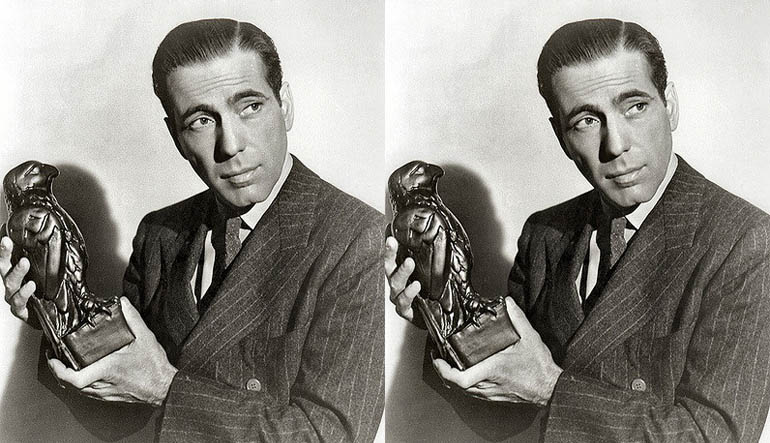

Humphrey Bogart, bringing the noir detective to life in the 1941 film version, levels his gaze and softly delivers Spade’s reply: “I’m going to send you over. Chances are you’ll get off with life…If they hang you I’ll always remember you.”

When you walk down that old avenue,

I just can’t believe that it’s you.

Painted lips, painted eyes,

Wearing a bird of paradise.

Well it all seems wrong somehow,

But you’re nobody’s sweetheart now.