East and West: What Tagore Loved to Eat

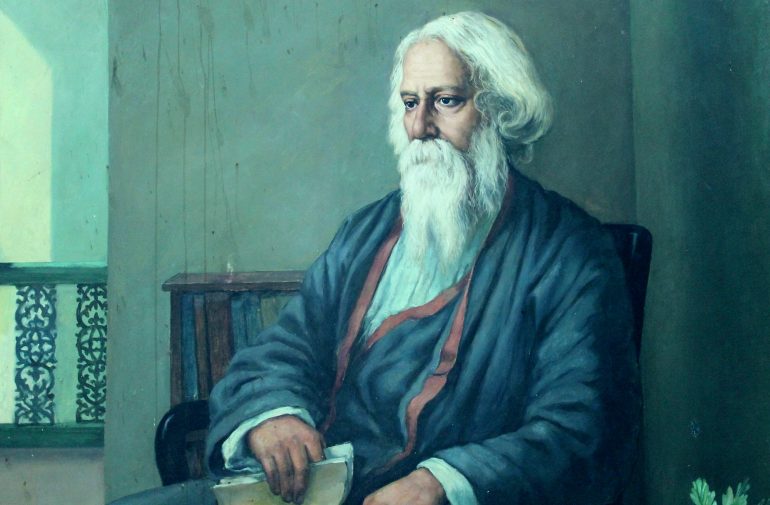

I wrote in an earlier post how I tried to reclaim poet Rabindranath Tagore as part of my heritage. He belongs to the soil of Bengal, where I was born. I had later moved to another state and to America, and then come back to Bengal, with only a smattering of Bengali literature in my blood–my father being an avid admirer of Tagore and his legacy. Over the past several months, I have steeped myself in Tagore, trying to imbibe his songs and poetry and to know him as a man. As a Nobel Prize winner and a towering literary figure, Tagore is a cultural icon of Bengal. I have sought his soul and prided myself in his glory. What kind of man was Tagore? All I have seen of him is his flowing beard in photos. Being a food-writing enthusiast and gourmet, I wonder what kind of food he ate. French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin famously said, “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.”

Tagore rarely wrote about his food experiences, but from his descendants and other sources we learn that he showed signs of being a gourmet. His childhood memoir, My Boyhood Days, contains few references to food. Even though he belonged to an aristocratic household, as a child, Tagore led a spartan life in keeping with his father’s instruction. Tagore lived surrounded by servants. In My Boyhood Days, he describes, without self-pity, the simple comfort food he ate in his home in Jorasanko, a neighborhood in northern Kolkata. In the slim book, referring to the food brought by a servant, he says, “It was luxury beyond our wildest dreams when our tiffin rations went beyond Brajeswar’s inventory and included a loaf of bread, and butter wrapped in a banana leaf.” Later on, he writes, “Small rations cannot be said to have made me weak. I was, if anything, stronger, certainly not weaker, than boys who had unlimited food.” Tagore seems to have eaten mostly home-cooked comfort food as a boy. In his memoir, he writes how welcome this comfort food was when he ate it after an illness: “After this fast, the mourala fish soup and soft-boiled rice which I got on the third day seemed a veritable food for the gods.”

The older Tagore, however, outgrew the simple provisions of his boyhood and apparently developed a taste for gastronomic delights. We get a glimpse of a richer, more aromatic and lavish fare on the table for Tagore from sources beyond his own writing. Even when he was a mere boy of eight, he wrote a limerick that stands the test of time. He, of course, wrote in Bengali, and it is difficult in translation to capture the nuance of native language and food. Here is an imperfect translation:

I drop amshotto (sun-dried ripe mango) in milk, I squash a banana into it

I mash shondesh (sweet) into this

The sound of slurping echoes in the silence

Even ants return empty-handed, shedding tears into my empty plate.

Tagore’s penchant for gourmet food came to light when, as an adult, he traveled the world and wanted to replicate in his home the food he ate abroad. Tagore was a frequent traveler and would often return with recipes he liked. The Tagore family’s cooking was an amalgamation of different flavors from India and overseas. For instance, he loved kebabs, some extremely offbeat. These kebabs started appearing on the family’s dining table.

Tagore’s wanderlust took him to Italy, Spain, England, and Turkey, and he imbibed the food traditions of those countries. Since he was exposed to both Asian and Western cuisines, a penchant to blend the two came naturally. The Thakurbari (the Tagore household in Bengali) kitchen struggled, with cooks toiling, to reproduce the magic of the food that lingered in Tagore’s mouth from his overseas trips.

Tagore loved pies, patties, roasts, and kebabs; chicken and mutton pies; prawn and ham patties; lamb and chicken roasted with breadcrumbs; prawn cutlets, and roasted mutton with pineapple. The exotic kababs that had charmed him are Surti Meetha Kebab, Hindusthani Turkish Kebab and Chicken Kebab nosi. Yet he was also fond of Bengali cuisine, especially fish, a staple of Bengal. His favorite fish dishes are kacha ilish er jhol, chitol mach aar chalta diye muger daal, narkel-chingri (shrimp in coconut milk), aadar maach (ginger fish), and bhapa ilish (steamed hilsa, a fish of the shad family).

The mingling of the East and West seems a hallmark of the Tagore household. Many of the other Tagores also loved to travel, and they picked up recipes from far and wide. The Tagores loved, for instance, sweets–the Bengali sweet tooth is legendary. In Thakurbari, one of the most well-loved was a dessert made from cauliflower, a deviation from the traditional chana (unripe curd cheese) sweets, or shondesh, which takes pride of place among Bengali desserts. A juxtaposition of Western and Bengali delicacies clearly held sway over the household.

The Tagores ate lunch like traditional Indians–sitting on the floor–but dinner at a table like Westerners. Tagore used Western cutlery and silverware.

I chuckle at this, for I use forks and spoons to eat, a habit I picked up during my years in the United States, where I lived for several years in the 1990s. What affinities I find between the bard and me I love and claim as my own! The comparison must end there, however. It would be effrontery and hyperbole to continue it.

But I adore him not just because of his genius. Tagore straddled the East and the West, and his thinking tended to be universal. It’s no wonder he came to love the pies and patties as much as his fish and rice. Like me, he absorbed the flavors of Western cuisines and assimilated them. The Bengali and Hindi word Visva, meaning the world, often describes his endeavors, like Visva Bharati, the university he established in Shantiniketan. He embraced the ideal of unity–not rejecting any culture or race. At the end of his boyhood memoir, he says, referring to the education he obtained from British acquaintances and his trip to England: “East and West met in friendship in my own person. Thus it has given me to realize in my own life the meaning of my name.” In Indian languages, rabi means the sun, which traverses the sky from east to west.