Fifty Shades of Heathcliff: Why WUTHERING HEIGHTS Isn’t a Love Story

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë is often considered one of the great Victorian romances, mentioned in the same breath as classics like Pride and Prejudice and her sister Charlotte’s most famous work, Jane Eyre. But where Jane is a love story through and through, from the early meet-cute to the closing “Reader, I married him,” Wuthering Heights is a “love story” only in the most literal sense. The narrative turns on the love between two people, but ultimately, it is the story of a dysfunctional relationship between highly destructive people, whom we’re not meant to “root for” any more than we are the central couples of Tender Is the Night or Revolutionary Road.

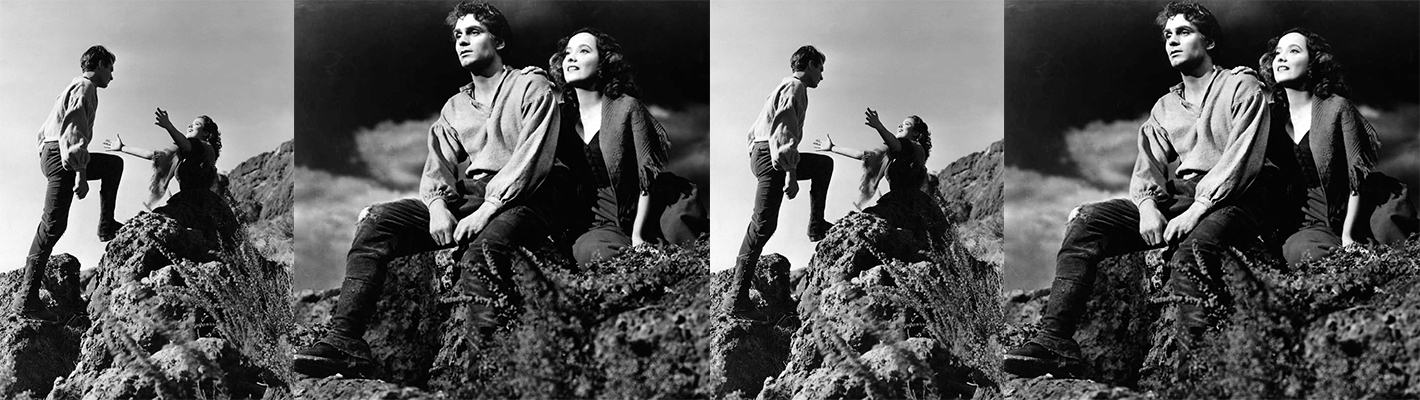

The character Heathcliff, in particular, has been remembered as the quintessential Gothic romantic hero. And there are trappings within the novel that encourage this interpretation; Heathcliff suffers a truly tragic childhood, he is a social outcast through no fault of his own, and while he demonstrates a capacity for cruelty early and often, he always refrains from victimizing Catherine. So as a result of conditioning from the tropes of countless romantic novels, the reader is primed to spend the entire novel waiting for Heathcliff’s inevitable redemption.

But the novel is brilliant precisely because it never indulges such romantic fantasies. Brontë shrewdly plays on the reader’s vicarious desire to “save” Heathcliff’s sensitive, tortured soul by opening with a stereotypically romantic premise, and then continually disabusing the reader of any notion that Heathcliff is somehow redeemable. His abusive relationship with the naïve Isabella, especially, is a indictment of his innately sadistic, even sociopathic character. She is an innocent, but he exacts psychological torment on her for sport, even going so far as to throw a knife at her at one point. In this episode, he himself admits that he is incapable of mercy or remorse: “The more the worms writhe, the more I yearn to crush out their entrails! It is a moral teething; and I grind with greater energy, in proportion to the increase of pain.”

As Joyce Carol Oates once noted, Isabella, with her grand romantic notion that Heathcliff is a hero despite mounting evidence to the contrary, becomes a stand-in for the audience; just as she waits in vain for Heathcliff to soften and show some semblance of humanity, so does the reader, until the bitter end. But even after Catherine’s death, our “hero” finishes the novel with his most damning statement of all: “I’ve done no injustice, and I repent of nothing.”

It’s an equally blistering indictment of modern American culture that after nearly two centuries, Wuthering Heights is still viewed as a “tragic love story.” Arguably the most popular romantic narratives in the last decade or so have been the Twilight series and its even more disturbing spawn, Fifty Shades of Grey. The former repeatedly references Wuthering Heights, but the latter, especially, shares superficial similarities with Brontë’s novel: like Heathcliff, Christian is a self-proclaimed sadist whom the female protagonist—and by extension, the reader—is tempted to excuse as a result of his pitiable, traumatic childhood. And like Heathcliff, Christian proves himself to be beyond rescue (except perhaps by a qualified therapist). Over the course of the novel, he coerces a young, inexperienced woman into a reluctant BDSM relationship and openly expresses a desire to control her in and out of the bedroom (“I don’t want to change you. I’d like you to be courteous and to follow the set of rules I’ve given you and not defy me. Simple”). And in the novel’s most unintentionally painful scene, Christian becomes equal parts angry and turned on when she won’t accept public sexual advances, and after she quite literally begs him not to hurt her, settles for nonconsensual sex without actual injury.

But Fifty Shades of Grey lacks the self-awareness of Wuthering Heights, and since it’s the kind of novel that traffics in references to Ana’s “inner goddess” and cringe-worthy sentences like “I don’t make love. I fuck… hard,” the reader is intended to root for Ana and Christian’s distressingly co-dependent relationship to prevail in the end. Ana stays with Christian not in spite of the abuse she’s forced to endure, but because of it, because she believes a healthy, functional relationship would be passionless and boring. The conflation of “passionate” love with difficult, dramatic love is ubiquitous in popular culture today; the television show Scandal, for example, also promotes an emotionally and sexually abusive relationship as an ideal. The most-shared quotation from Kerry Washington’s Olivia Pope, who is often hailed as a rare strong female protagonist of color, tellingly reads: “I don’t want normal, and easy, and simple. I want painful, difficult, devastating, life-changing, extraordinary love.”

The quotations that have endured from Wuthering Heights are eerily similar; a quick search on Pinterest or Tumblr will tell you that the most iconic passages from this nuanced meditation on human nature focus on Heathcliff and Catherine’s unhealthy identification with each other. When Catherine dies, Heathcliff exclaims, “I cannot live without my life! I cannot live without my soul!” and, most famously, Catherine at one point says, “I am Heathcliff,” and goes on to declare, “He’s more myself than I am. Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same.” But unlike Fifty Shades of Grey and Scandal, which intend to romanticize the central relationships, these quotations are taken woefully out of context. Immediately prior to Catherine’s soliloquy, she tells Nelly that she belongs with Heathcliff precisely because “If [she] were in heaven, [she] would be extremely miserable.” They don’t belong together because their love is exceptionally pure; they belong together because he is destructive and she is self-destructive.

In fact, a closer analog for Wuthering Heights in popular culture is decidedly not a love story at all. Marvel’s Jessica Jones, which follows a woman who was forced to have sex and commit criminal acts while under mind control, is a feminist narrative that actively subverts similar romantic tropes. The villain, Kilgrave, is a terrifying sociopath, but a handsome, charming one with a tragic childhood who is often quite sympathetic. There’s even a tiny bit of ambiguity as to whether Jessica is attracted to him. But his attractiveness is always treated as immaterial, and while his backstory elucidates him, it doesn’t excuse him. Jessica openly characterizes his actions as “rape,” and never seriously considers the possibility that a person capable of such violence can ever be trusted. And yet, even with this canonical dismissal of rape as an erotic device, there is still a wealth of fan fiction in support of the Jessica/Kilgrave relationship. Even outright calling him a rapist doesn’t stop viewers from rewriting him as a romantic antihero who can be “saved,” demonstrating the inescapable, tentacled reach of this retrogressive narrative.

Similarly, readers’ projections aside, there is no “love story” within the pages of Wuthering Heights (at least not between Catherine and Heathcliff, although a case can be made for Cathy and Hareton in the oft-forgotten second half). Indeed, Wuthering Heights is a story that deeply believes in evil, and aims to expose the dark side of human nature. Heathcliff himself warns Isabella against “forming a fabulous notion of [his] character,” and thereby warns the reader against the naïve supposition that an abusive sadist can necessarily be redeemed. Wuthering Heights serves as a refreshing antidote for the tired love-as-pain narrative, but nearly two hundred years later, we still haven’t taken its wisdom to heart.