How We Belong Somewhere

How does a poet come to belong to a place? Who are the poets of our American places?

How does a poet come to belong to a place? Who are the poets of our American places?

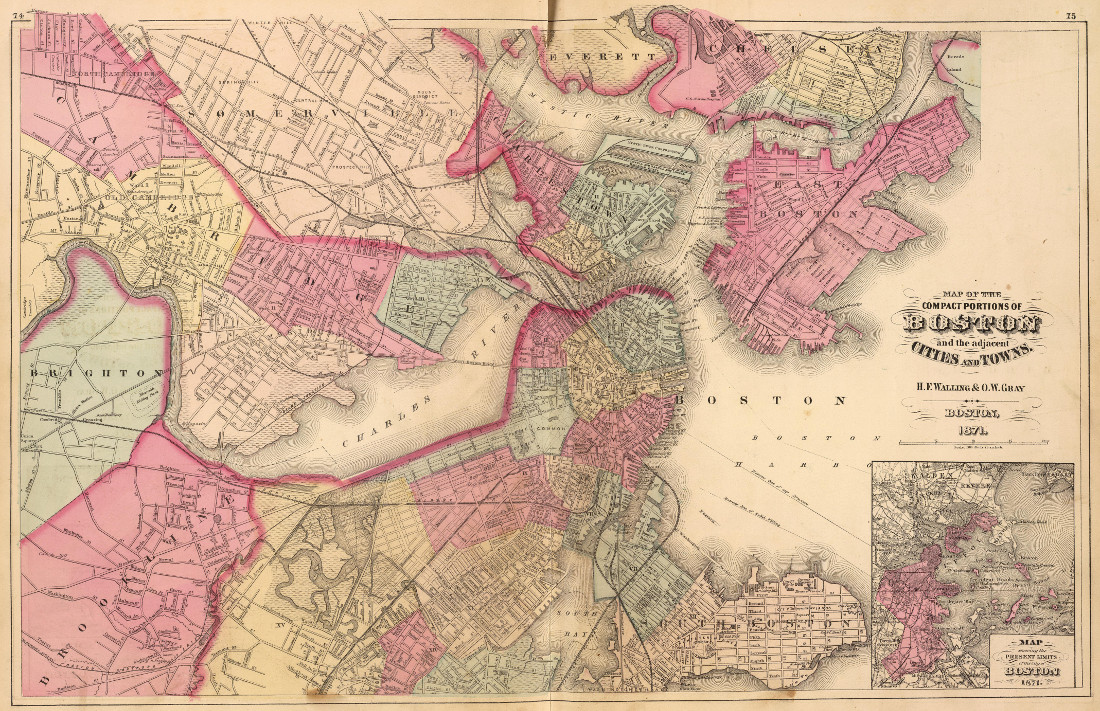

As I travel in and around Boston I’m reminded of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. His verses leap to mind when visiting Plymouth, the Wayside Inn in Sudbury, or the Old North Church in Boston’s North End:

Listen my children and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

Longfellow has a taste for the heroic, the dramatic, and the sentimental. He invokes famous public figures and settings, and his bouncy rhythms and easy rhymes are easy to memorize.

But any poet today who shared Longfellow’s taste would be laughed out of the room. He wanted heroism; we want the ordinary. He wanted grand dramas; we want insightful understatement. He wanted music; we want images. Consider an early example of modernist poetry, T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Boston Evening Transcript’:

The readers of the Boston Evening Transcript

Sway in the wind like a field of ripe corn.When evening quickens faintly in the street,

Wakening the appetites of life in some

And to others bringing the Boston Evening Transcript,

I mount the steps and ring the bell, turning

Wearily, as one would turn to nod good-bye to Rochefoucauld,

If the street were time and he at the end of the street,

And I say, “Cousin Harriet, here is the Boston Evening Transcript.”

It’s subtle, but Eliot does reveal something of what Boston was like in the early 20th century: an easily swayed educated class hungry for manipulative journalism, divisions between the “some” with their appetites and the “others” with their newspapers (evidence of the widespread crisis in masculinity and increased immigration), and snide young men judging their established relations even while relying on their old money. It’s a young person’s poem—poking fun at the establishment and pretending to world-weariness in order to seem deep—but Eliot manages to capture a society in nine lines.

And yet. The poem doesn’t tell us about any recognizable places or characters. It’s too wry and skeptical to make us feel a connection to the place. Even though Eliot was shaped by Boston and had interesting things to say about it, he doesn’t belong to Boston, and Boston doesn’t belong to him. Just based on this poem, where could you go in Boston and say, “This is the place Eliot was talking about”?

The truth, I think, is that nobody can ever upturn Boston’s founding literary figures: Longfellow, Wheatley, Emerson, Alcott, Thoreau. They were here first; the city is theirs. But it’s not a question of whether they can be bested; it’s a question of whether the game they won can even be played anymore. We live in a more skeptical age. We acknowledge that our society was built on imperfect foundations and so look for strength in the present as well as in past. The places we live in are enriched through the living testimony of a plurality of voices. Here’s “Boston Year” by Elizabeth Alexander (from poetryfoundation.org, originally appearing in The Venus Hottentot, Graywolf Press 2004):

My first week in Cambridge a car full of white boys

tried to run me off the road, and spit through the window,

open to ask directions. I was always asking directions

and always driving: to an Armenian market

in Watertown to buy figs and string cheese, apricots,

dark spices and olives from barrels, tubes of paste

with unreadable Arabic labels. I ate

stuffed grape leaves and watched my lips swell in the mirror.

The floors of my apartment would never come clean.

Whenever I saw other colored people

in bookshops, or museums, or cafeterias, I’d gasp,

smile shyly, but they’d disappear before I spoke.

What would I have said to them? Come with me? Take

me home? Are you my mother? No. I sat alone

in countless Chinese restaurants eating almond

cookies, sipping tea with spoons and spoons of sugar.

Popcorn and coffee was dinner. When I fainted

from migraine in the grocery store, a Portuguese

man above me mouthed: “No breakfast.” He gave me

orange juice and chocolate bars. The color red

sprang into relief singing Wagner’s Walküre.

Entire tribes gyrated and drummed in my head.

I learned the samba from a Brazilian man

so tiny, so festooned with glitter I was certain

that he slept inside a filigreed, Fabergé egg.

No one at the door: no salesmen, Mormons, meter

readers, exterminators, no Harriet Tubman,

no one. Red notes sounding in a grey trolley town.

This is Boston. There are people who have been here for generations—in this case Cousin Harriet and Tom Eliot are replaced by “a car full of white boys”—but there are also Armenians, Chinese, Arabs, Portuguese, Brazilians. The poet feels more comfortable with them than with other African Americans, and even then the relationships are based almost entirely on food. Her relationship with the dance instructor seems a little deeper than the others but is connected to the image of a Fabergé egg—food that cannot nourish, a semblance of life without the substance. Literal hunger and metaphorical hungers for companionship, knowledge, and experience drive the poet forward, even though they don’t make her happy. She doesn’t thrive; she endures. She combines the quiet nobility of Longfellow’s village blacksmith with the starving hysterical nakedness of the best creative minds.

In contemporary poetry, a poet belongs to a place through earnest relation of their real life in that place. Elizabeth Alexander shares what Boston was to her and what she was in Boston. It’s a hard story, but its honesty radiates over the people and places of this city. And the heroism of just telling the truth can radiate everywhere that people practice the craft of poetry.