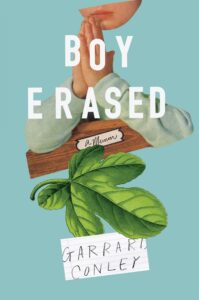

In Bookstores Near You: Boy Erased by Garrard Conley

Depicting his time as a “patient” in the ex-gay therapy program known as Love in Action (LIA), Garrard Conley’s Boy Erased opens in a way that reminds me, eerily, of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. In the first paragraphs of her novel, Atwood grounds her alarming sci-fi world in details we can fathom: the training center for handmaids is housed in an old high school gymnasium we recognize—the hoops for basketball nets; the lingering taint of sweat, chewing gum, girl’s perfume; and the memory of school dances with garlands of tissue flowers, revolving disco balls, the drum-heavy music. In the same way, Conley must situate his readers to the bizarre world of conversion “therapy”: LIA operates in a familiar red-bricked strip mall, the rooms small and halogen lit, the walls empty of all but the Twelve Steps promising a slow but steady cure. Both books contemplate what happens when religious ideology runs amuck, destroying the lives of some in order to grant privilege to others. Here’s the difference between the two stories: Conley’s is not make-believe. It’s not science fiction. This is 2004.

The chapters in Conley’s memoir rotate between his ten days at the facility and his life outside leading up to his enrollment. It’s hard to say which half of Conley’s story is the most painful: his struggle to fit in and accept himself as a homosexual in the outside world or his attempts to erase his identity in the course of “therapeutic” activities at LIA. Outside, Conley struggles to maintain a relationship with a girl, overcome his first sexual experience (a rape committed by another boy at college), and meet his ministerial parents’ expectations of him. Always, he wonders about heterosexual privilege–what it’s like “to see yourself reflected in every movie, to have friends and family constantly dropping fun little hints about your love life, to have the world open up to you in all its magnificence.” He can’t imagine the freedom that comes from living as if no one is scrutinizing your every behavior. As evidenced by the archival footage used in the trailer, if we inspect “normal” behavior–even those images dating from the so-called clean 1950s—as thoroughly as society judges the LGBTQ community today, “normal” can start to look “different.”

When a well-meaning doctor assures Conley that he can live the life he wants if he moves away, starts over, Conley admits that “cutting away [his] roots,” the people he loves, in order to live in a gay-friendly community, saddens him more than the thought of suicide. And so he willingly enrolls in LIA—a desperate attempt to cure himself, to learn the characteristics he thinks he should embrace to be who society wants him to be. Abiding all the program’s rules, he abandons books, reflection, friends, hobbies. He erases “every minor detail” of his history and personality. Ultimately, he quits the program only after the lead counselor forces him to take the stage in a group session and lay blame for his identity on his parents: he must be angry at them; it must be their fault; he must betray them and make this admission. He refuses.

Conley ends the book with a confession: he has not healed. He remains a ghost in his childhood home; his relationship with his father is still strained; he can’t sustain a relationship with any man. But he also insists that he loves his father and does not blame him, even as the image motifs of the book might suggest a more complicated psychological struggle. His father’s face was burned and disfigured when he acted the good Samaritan and fixed a car on the side of the road but the driver turned the key in the ignition while Conley’s father was still under the bumper and had warned him not to. LIA attempts to explain away Conley’s homosexuality through a genogram whose “key” lists every familial “sin” supposedly leading up to the boy’s sexual orientation. And Conley’s first sexual experience—the incident that nearly convinces him that homosexuality is the evil equivalent to rape—happens when another young boy shoves Conley’s face toward the “keyhole fly” of his briefs, forcing Conley to go down on him.

Several motifs like this one run throughout the book. Whether intentional or subconscious, these recurring images teach us how complicated and psychologically damaging it is when men and women must live in a world where we ask them to split their identities—hiding one in private, faking another in public.

Video: Archival footage by the Missouri Division of Health, Pacific Productions, Pathescope Productions, and Prelinger Archives. Music: Gymnopéde, No. 1, by Erik Satie, performed by Frank Glazer.