Let’s No One Get Hurt by Jon Pineda

Let’s No One Get Hurt: A Novel

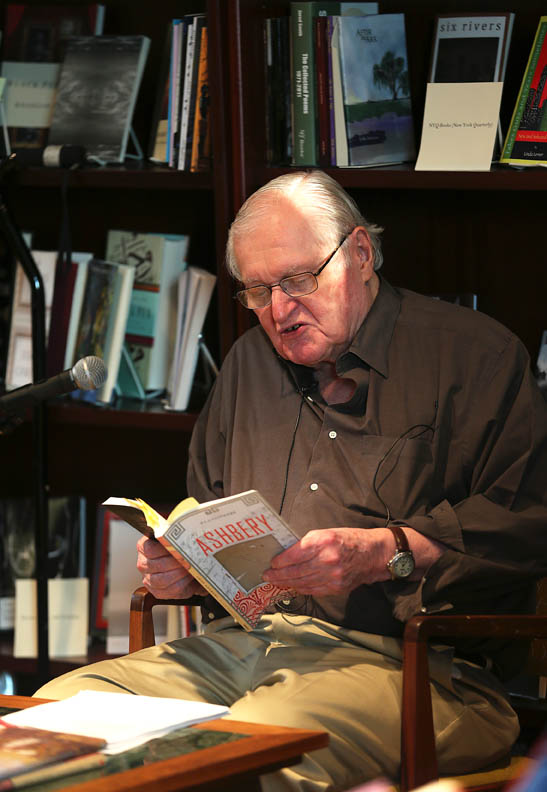

Jon Pineda

Farrar, Straus and Giroux | March 20, 2018

Amazon | Powell’s

Jon Pineda’s new novel has a vaguely apocalyptic feel as 16-year-old Pearl squats on abandoned property with her father, an alcoholic former professor of modernist poetry, family friends Dox and Fritter, and a dog named Marianne Moore. But the only apocalypse is a personal one for Pearl as she comes of age while navigating this completely male world in which she finds herself and its undercurrents of violence.

Pearl and her father arrived there four years ago in a “faded yellow Gran Torino station wagon. . . after my mother left us.” Foraging and fishing to survive, the four create a pale imitation of an artist’s colony, with crab boils, music, dancing, and a mural that is actually, Pearl discovers, just a wall being painted black over and over. The novel opens at a moment of crisis for Pearl: told to shoot the family dog, she is also coming to realize more fully her father’s limitations, saying, “If I’m anyone’s girl, I’d have to be his by default. . . It’s been getting more difficult. The more I catch glimpses of what kind of man he really is.” A tough girl with hidden vulnerability, Pearl is haunted by the loss of her mother, a translator of classic French poets, struggling with her memories of her mother’s desperation and tenderness and their family’s troubled relationships.

Pearl, who has a secret longing for normality, for dates and dances, falls in with a group of boys from wealthy families. The “sons of land developers, judges, and weekend Civil War reenactors,” they live in “behemoth McMansions,” dress like they’re in a “high-end clothing shoot,” and travel around in tricked-out golf carts. As a girl from a lower socioeconomic status among these spoiled, misogynist boys who spend their days looking for a prank in pursuit of a viral YouTube video, Pearl will always be an outsider. Nevertheless, she allows herself to become involved with their leader, Mason Boyd, whom she refers to as Main Boy and who often treats her cruelly.

Despite her deprivation, Pearl finds a deep connection to the river and to African American family friend Fritter as, in a Huck Finn-like passage, they travel in a raft to find her father after he has been hospitalized. And Fritter also emerges as her protector when she becomes the victim of a brutal prank by the boys she has uneasily befriended.

In Pearl’s first meeting with Mason, her toughness is on display: he promises to teach her how to “shoot if I kiss him and maybe kiss a few of the others. I tell him he won’t have to teach me: if he tries to kiss me, I’ll be able to shoot just fine.” The psychology that leads her to eventually be sucked into more romantic dreams is believable though not entirely convincingly developed, perhaps due to Pineda’s spare writing style reminiscent of late 1980s minimalism and the fragmented structure that at its best echoes Pearl’s psychological state.

A poet as well as a novelist, Pineda brings an evocative, compressed style to this work, richly mining its resonances despite its occasional tendency to succumb to a kind of flatness that often marks minimalist writing, particularly when it comes to exploring Pearl’s contradictions and the aftermath of the loss of her mother and her revelations about her father. But his lyricism and precision tend to hit the mark, as when Pearl describes the river gathering at her waist, “then runs long, sweeping folds down to my ankles. It feels like a fitted dress,” when sailboats in the distance have “open sails. . . like the petals of fragrant water lilies,” or, especially strikingly, when she describes Fritter’s dreadlocks as “frozen paths of fireworks.” Pineda also captures the absurd socioeconomic and cultural disparities of this world in such moments as when Pearl, Fritter, and her father are forced to walk through a Civil War reenactment, spoiling their battle. Pineda writes, “Union and Confederate alike, raise themselves up from where they’ve fallen so they can flip me off properly.”

“Careful now,” says family friend Dox in a flashback during a fishing expedition. “Let’s no one get hurt.” By the end, Pearl is able to firmly place her relationship with Mason in the past. “I only wish I could say no one got hurt,” she says, but raw as she is, we have seen that she has the tools to survive.