Macedonio, Argentina’s Man of Letters

Most long-dead literary circles have unsung heroes, authors who were important when they were alive but have since fallen through the cracks of history for one reason or another. Sometimes, their work has aged poorly. Other times, translations have proved tremulous, or manuscripts have been either lost or destroyed. Macedonio Fernandez is one such figure—he is now almost completely unknown outside of his native Argentina, and even in Argentina is more a folk hero and less a national icon. In spite of this, Macedonio (usually referred to by his unusual first name) is the backbone of 20th century Argentinian literature.

Although Macedonio’s legacy is partially due his role as the Godfather of the Argentinian literary circle Los Escritores Malditos and as Argentina’s first metaphysician, he is known mostly because of his role as Jorge Luis Borges’s mentor. Macedonio attended law school with Borges’s father, and they met when Borges, 22, had just returned from Europe. The intensity of their friendship was threatened after a dispute in the late 1920’s; it recovered not long after but never reached the level of intimacy the two shared prior to the dispute. Borges himself acknowledged Macedonio’s influence on him during young adulthood, once stating, “I imitated him to the point of devoted and impassioned plagiarism. […] Macedonio is metaphysics, is literature. Whoever preceded him might shine in history, but they were all rough drafts of Macedonio, imperfect previous versions. To not imitate this canon would have represented incredible negligence.”

Critics quibble about the extent of Macedonio’s influence on Borges, as critics are wont to do. Noé Jitrik, arguably Argentina’s leading literary critic, sums up the debate nicely in an interview with the Argentinian newspaper Clarín: “Borges is a product of Macedonio.” Does Borges make it in the tenuous world of letters without Macedonio? Probably. He was a precise stylist and a fantastic short story writer. Borges’s ideas, though, are at least partially a result of his conversations with Macedonio. The inverse is inevitably true as well, though, Borges is in part responsible for the mythologizing of Macedonio, of cultivating his portrait as an ascetic mysticist devoted only to reflection and ideas.

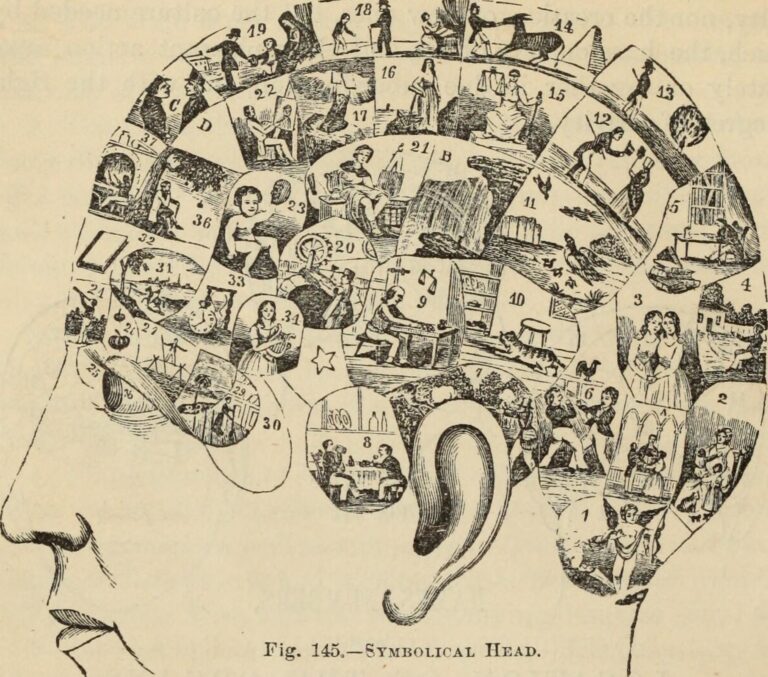

Macedonio was obsessively concerned with the role of the reader, a minor irony considering he was apparently disinterested in publishing the vast majority of his work. One of the many mythologies surrounding Macedonio says that he “wrote on crumpled cafe napkins, that he used to light the stove or his cigarette with loose manuscript pages, or that he piled them up in suitcases, only to abandon them when he moved from one flophouse room to the next.” Similar to the legendary myth of Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin smoking his only copy of a book-length study on the Bildungsroman during the Siege of Leningrad, stories like these will probably never be verified, nor should they be. Verisimilitude is a poor trait for a metaphysician.

Other fantastical stories about Macedonio include founding an anarchist commune in Paraguay but calling it quits after an evening of incessant mosquitos, giving away his guitar at random to a street urchin, and befriending the ants in a run-down boarding house and periodically giving them food to eat. Another alleged plan involved Macedonio running for president through a series of surrealist pranks. Macedonio inevitably belongs to that unfortunate horde of authors who are more frequently talked about than actually read, and will probably always be more well-known by his relationship with Borges and anecdotal eccentricities than by his writing.

Macedonio’s most famous book The Museum of Eterna’s Novel (The First Good Novel) was first translated to English in 2009. To say that the novel is preceded by some 57 prologues is misleading, because these prologues constitute over half the length of the book and are part of the fabric of the book itself. There is a loose (very loose) conventional plot surrounding a group of friends on an estancia (country home) and a war in Buenos Aires taking place between two literary gangs called the Romantics and the Jubilants, but the vast majority of the book is made up of meandering lamentations on the distinction between being a character and a living being, the futility of realism, and the relationship between art and life. In some sense, it was a sort of creative attempt at providing a theory of the novel.

Macedonio was infinitely more gentle in his writing than his protégé Borges could ever be, and in between his bits about being and non-being and what it means to be a character in a book, Macedonio is heartbreakingly tender. Early on in the novel, Macedonio writes, “Death is only the death of love; there is only the death of the other, her concealment, since for oneself there is no concealment.” Beneath all of the metaphysical riddles that The Museum of Eterna’s Novel poses, Macedonio the metaphysician was surprisingly human, and far more interested in our relationships with other people than Borges’s portrait of him as a reticent sage suggests. In a diary entitled “Ser Feliz” (to be happy) that Macedonio wrote as a young man, a passage reads, “Eat very little, wear your long underwear when the weather gets cold, don’t complain, don’t smoke too much, get enough sleep. Remember the good people, and do not make them unhappy. Stop touching your mustache. Make ample use of toothpicks.”

It is part of the ritual of myth-making to forget about the peculiarly human bits of a personality, about the less fantastical parts that make up a whole. Macedonio as Borges’s enigmatic teacher will probably endure, but it is Macedonio the thinker and occasional writer who deserves more attention. Few writers have straddled the line between the metaphysical and the utterly human quite so well.