Obama & GILEAD: Lessons on Loving Thy Neighbor

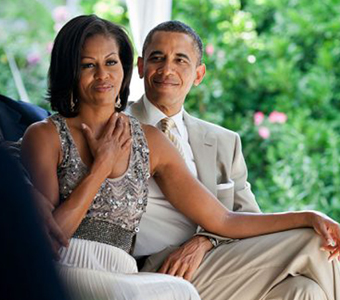

Recently, an interview that Barack Obama gave in 1995—which was republished in The New Yorker just before the Presidential Inauguration in 2009—made the rounds on social media again. Speaking of Michelle, Obama said:

“[S]he is at once completely familiar to me, so that I can be myself and she knows me very well and I trust her completely, but at the same time she is also a complete mystery to me in some ways. And there are times when we are lying in bed and I look over and sort of have a start. Because I realize here is this other person who is separate and different and has different memories and backgrounds and thoughts and feelings. It’s that tension between familiarity and mystery that makes for something strong, because, even as you build a life of trust and comfort and mutual support, you retain some sense of surprise or wonder about the other person.”

In January, I wrote about President Obama’s affinity for Gilead, Marilynne Robinson’s 2004 Pulitzer Prize winning novel. In my weathered copy of the novel, one of the most marked-up passages reads eerily similar to Obama’s musing. Directed to his son, the Reverend John Ames writes:

“In every important way we are such secrets from one another, and I do believe that there is a separate language in each of us, also a separate aesthetics and a separate jurisprudence. Every single one of us is a little civilization built on the ruins of any number of preceding civilizations, but with our own variant notions of what is beautiful and what is acceptable—which, I hasten to add, we generally do not satisfy and by which we struggle to live. We take fortuitous resemblances among us to be actual likeness, because those around us have also fallen heir to the same customs, trade in the same coin, acknowledge, more or less, the same notions of decency and sanity. But all that really just allows us to coexist with the inviolable, intraversable, and utterly vast spaces between us.”

Here, Ames yearns to understand the heart of another man, the ways and reasons of Jack Boughton, his namesake, the child of his best friend. Boughton’s life is comprised of choices that the pious Ames does not agree with, but ultimately, Ames discovers that Boughton’s life is laden with complications he wouldn’t have dared to imagine. This moment is immensely humbling for Ames, a man who’s spent his life ministering in an intimate congregation. Attached to this humility, however, is fierce reveling in the mystery of creation.

Both Obama and Ames marvel about the mystery between intimates, about the possibility of distance between those who are closest. But their implication here is broader. That we can be neighbors, yet be worlds apart, that we’re tasked to love this oft-mysterious neighbor as thyself: the acknowledgement itself here is humbling. It’s an admission that one can’t always know what’s best. And in both passages the admission comes from leaders. One man presides over a small flock, the other man is the veritable leader of the free world.

This election cycle, numerous articles have spoken of empathy, or the lack thereof, among certain candidates. I want elected officials who will try to imagine themselves as the single mother working three jobs or the partner of an LGBT Latino man slain in Orlando. I want elected officials who will put significant work into this imagining, yet acknowledge where the limits of empathy lie. Because at that limit is where you turn to the person next to you—Barack to Michelle, Ames to Boughton—and listen, tuning an ear, basking in the wonder of difference.