On Being An Impostor: This Girl’s Life

—Bill Murray

I should have graduated high school in the year 2000. I was young for my year and, as my mother put it, “immature.”

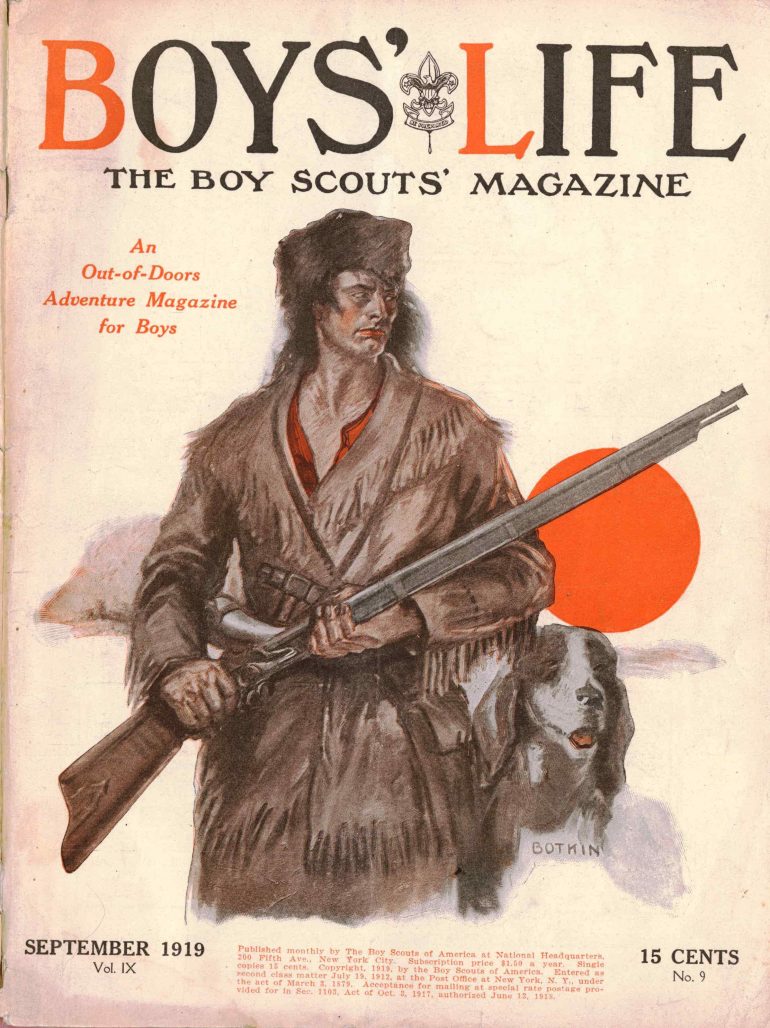

Instead of plodding along through public school, I spent tenth grade begging my parents to allow me to apply to The Hill School, an all-male boarding school my father had attended. In 1998, Hill went co-ed. By the time my parents relented and the school gave me a scholarship, the film Rushmore was out in theaters. I went to see it knowing I was sentenced to another two years of high school, a grand total of five.

Rushmore is the name of an all-boys’ private school that the protagonist, Max Fischer, attends on a scholarship he won with a play he wrote in elementary school. After the death of Max’s mother, Rushmore becomes his life. As a sophomore, Max forms an unlikely friendship with Herman Blume, a wealthy industrialist whose sons attend Rushmore. Blume, played by Bill Murray, asks Max to come work for him, to which Max responds that his father may only be a neurosurgeon, but they get by. In reality, Max’s father is a barber. Nearly two decades later, the moment in the film that still draws blood is when Max insists on treating the cast and crew of one of his plays; he hands cash over to an underclassman with the mandate to buy sodas for “whoever wants one…I don’t want one.”

The first thing I noticed at Hill was how ruddy the faces were; how everyone had money for snacks at the student Grille, for delivery food. How everyone had money.

I didn’t bother trying to buy people sodas. The money I earned over the summers went to books, and I wasn’t directing anything. Instead, I was trying to figure out how to wear a blazer. The last year of the century was not a good time for women’s blazers. My mother bought me two enormous ones from Eddie Bauer. They had shoulder pads and hit mid-thigh; underneath, I wore several sweaters to keep warm while rushing between the buildings on campus.

Perhaps to Hill’s credit, the newly co-ed school did not know how to dress young women, either. The thirty or so of us were expected to dress like boys, minus ties, unless we wore skirts, in which case we had to wear pantyhose. Mine were constantly getting caught on the old wooden chairs in the dining hall. My face didn’t look so great because I stayed up all night studying. During the day, the only way to reach my old friends was to call the pay phone at the public school, which generally didn’t work. The phone I used at Hill was in the Map Room, the social equivalent of steerage. I don’t remember having many new friends, but there are a few interactions I can’t forget.

“Why are you always doing work?” asked the most popular boy in my class, whose family came to America on the Mayflower. The blood still rushes to my face. Did I smile, apologize, or both?

“You’re the smartest girl I know,” said the Spaniard who didn’t want to be my boyfriend. It was gentle compared to his signature phrase, Do me a favor and die, OK? Thanksssss. Somehow, I’d been able to coerce him into even talking to me. To be his friend, I’d have to be a boy, a category I’d obviously failed. Beneath those enormous blazers and sweaters and torn stockings, I had no idea how to be a girl. My father was an alumnus, I was on scholarship, and I was a fraud.

My brothers attended Hill after me. High school wasn’t easy for either of them, but they were tri-varsity athletes and good-looking guys. Team runs were named after them. For a few years in my twenties, I returned to Hill and taught kids who still idolized my brothers. Being the dorm-parent of twenty teenage girls took at least a couple years off my life.

“I don’t trust anyone under the age of thirty,” said one of the girls on my hall.

She might as well have painted IMPOSTOR on my door. And yet it wasn’t until this winter, a bit after thirty, that I read the memoir of Hill’s most famous impostor, Tobias Wolff.

In This Boy’s Life, Wolff recounts how he fabricated his entire Hill School application. Desperate to escape an abusive stepfather, he wrote his own letters of recommendation, made up his own academic history, everything. Though his estranged brother and father had attended boarding schools, Wolff hadn’t even heard of Hill until his brother recommended it; he had to look it up at the library. What surprised me was how brief a time his narrative spends at Hill. There is no need for Wolff to spend more than a few paragraphs on the school, because the real story is how he became the sort of boy who could lie–who had to lie–in order to get there.

What I wish I had read in 1999 was how even being a boy can be a fraudulent act. Max Fischer was one kind of impostor, but Wolff took it to a whole other level. He writes of his closest friend: “I could accept the distance growing between us. I wanted it there, most of the time. But I could not accept that he knew I was not the person I tried so hard to seem. For owning such knowledge there could be no pardon, for either of us, until we both pardoned ourselves for being who we were.”

How different might my Hill School have been, if I had known even boys can’t always be themselves?

“I’ve given it some thought,” said a fifth grader I tutor, “and I’m not going to be popular, so I want to be the smartest.”

This is a narrative I know.

“I bet those old guys are rolling in their graves,” my dad crowed when I was the first girl to win the scholarship for Hill students matriculating to Yale. As far as I know, my father is the only graduate to leave Oberlin more conservative than he arrived. Yale hadn’t been on my parents’ agenda. In fact, until a teacher, herself a member of the first co-ed Yale class, suggested I apply, the only thing on my agenda had been to escape Pennsylvania.

At my rowdy five-year Hill reunion, a classmate let me know that he had thought I’d taken his place at Yale. As if he’d had one ready and waiting for him. As if I’d just shown up and stolen it. As if everywhere I went, I was a fraud.

And yet, if I can claim kinship with Wolff, I dare to say we held our own in the places we supposedly stole. These might be claims of outsized ego; they might be wholly American; they might be both. It’s pretty easy to spot frauds around these parts. There is something, though, to knowing you’re not guaranteed a place. There is something to having to claw your way in, wherever “in” is. And whoever has had to do that–those people are my people. As Murray says to a chapel full of Rushmore boys: “For some of you, it doesn’t matter: you were born rich and you’re going to stay rich. But here’s my advice to the rest of you: take dead aim on the rich boys. Get them in the cross hairs and take them down. Just remember: they can buy anything, but they can’t buy backbone. Don’t let them forget that.”