Pamp’s Books

At the change of each season, I take my grandmother to replace the cemetery flowers at our family plot on a sloping hillside overlooking McCaysville, GA. A ritual I associate with small town Appalachia, it’s a process of family remembrance—a sign of transhistorical care for the dead. Over the years, my gran has built a kit: cloth and brush for cleaning the grave markers, a garbage bag of greenery for fullness, Piggly Wiggly bags stuffed with artificial, multicolored bouquets, and a vodka box of floral foam bricks. The size of the kit and the long drive between my grandmother’s current home in north Alabama and the cemetery has made me a necessary addition: part chauffeur, part grave cleaner.

This past October, Gran had just finished detailing her run-in with a headless ghost on Highway 64, a twisting piece of road that cuts through the Ocoee River Gorge in southern Tennessee. Her memories of the ghost’s backstory were sparse, but she swore she saw the headless woman thirty years ago at a bend in the river, perched above the rapids. Midway through her speculation about the cause of the ghost’s condition—a turn taken too fast, side-swiped by a mining transport, domestic violence—she broke off abruptly: “Before I forget, I want you to take a look at Pamp’s books when we get home.”

The connection between headless ghost women and Pamp, my grandfather’s father, might seem tenuous. To my knowledge, Pamp had never seen a ghost, and he departed life at age eighty-one with his head intact. But I suspect it had something to do with a horrifying portrait of the head of John the Baptist—eyes bulging, mouth agape, splayed on a serving platter—that hung in the entry to his home. That was the kind of man Pamp was: a Church of God pastor, devoted to his religion, with a macabre streak.

This wasn’t the first time she’d asked me to look at the books. They’d come up every drive for the past four years, but I had been pushing them off. My interest was presumed because as I child I’d read anything from fable collections to catalogues of North American insects, and my career as a literature professor only seemed to underscore that I would (still) read anything. I’d become something of a family book repository, collecting battered copies of family favorites—Gulag Archipelago, One Hundred Years of Solitude—which rested somewhat uneasily next to odes to libertarian idealism—Atlas Shrugged, Lonesome Dove. Pamp’s books I suspected would be closer to the latter than the former. And they kept coming back no matter how much I ignored them—a return of the literary and ancestral repressed.

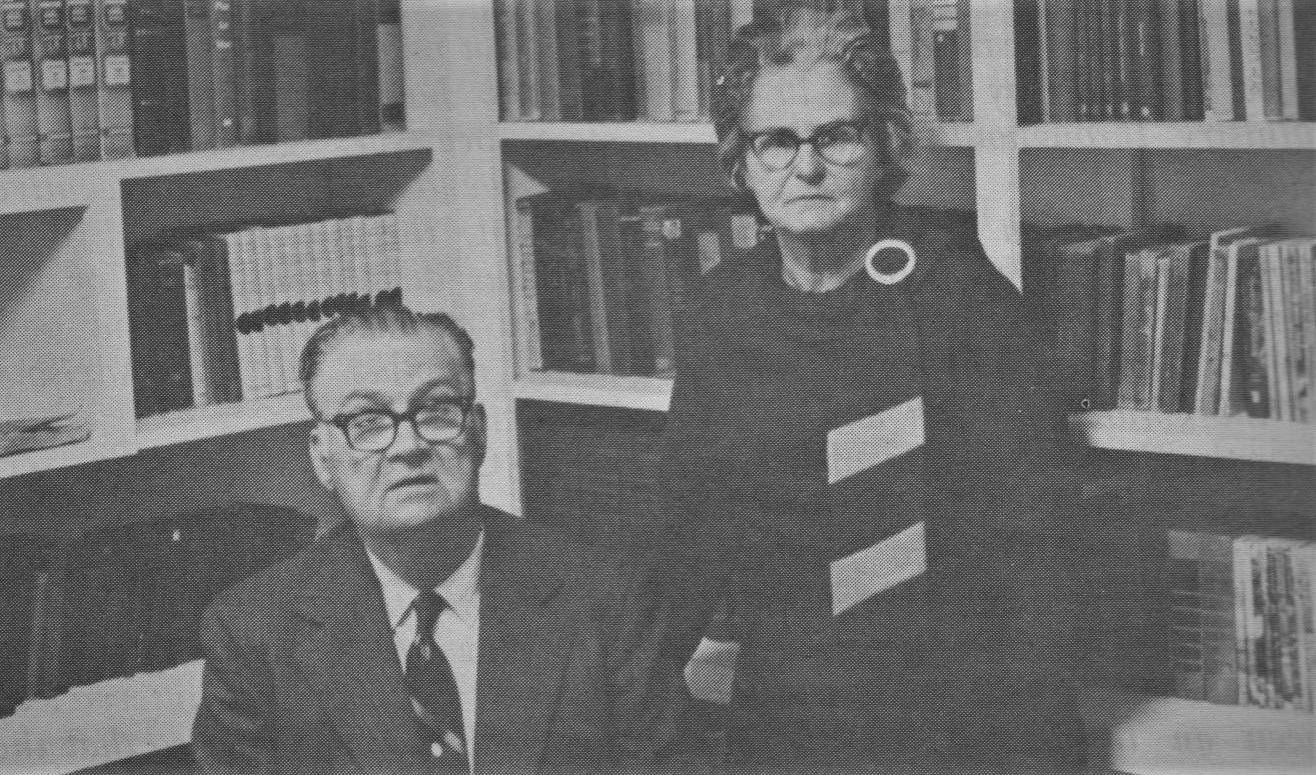

I never met Pamp. Albert Vardaman “A.V.” Beaube died in 1985, three years before I was born. I did know his wife, my great-grandmother, Laura, whose home I remember being uncomfortably quiet and dark (John the Baptist didn’t help). Born in 1901, he was raised in Meadville, MS but spent most of his life in north Alabama and Georgia. He was a father of ten, a large family that lived on the edge of poverty for most of his life. Pamp worked as an itinerant pastor in the Church of God, a Christian evangelical denomination headquartered in southern Appalachia. While Pamp was alive, the church discouraged “worldly amusements” such as cosmetics, dancing, and mixed-gender swimming. His obituary extolls him for “his multiple years of service as pastor, state overseer of several states, assistant general overseer and member of executive council and advisory board.” His ministry was such that you can still see his papers at the Church of God archives at Lee University in Cleveland, TN.

That record of exemplary church service and devoted leadership, however, was not reflected in my family remembrance. What I learned about him, I learned in praeteritic snatches, the barest hints of suggestion that implied uncomfortable truths while also never quite affirming them: “[A.V.’s eldest daughter] always said that the Church of God was founded by women. The men drove them out when they saw how profitable it was.” “He asked me once to write him a prayer. When he read it, he said it’s exactly the kind of prayer a woman would write.”

And there was the long-standing rumor that Pamp dabbled in snake-handling. A fringe Appalachian evangelical movement that started in the early twentieth century, practitioners handle poisonous snakes, taking literally the biblical promise: “Behold, I give unto you power to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall by any means hurt you” (Luke 10:19). Supposedly “if you went past noon on Sundays to Pamp’s church…who knew what you might find.”

Beyond rumor, however, there was fact. Of his ten children only one, Valerie, stayed in the Church of God. The rest, including my grandfather, George, fled. These pieces of family history offered a piecemeal image of Pamp—a possible fanatic; a misogynist whose own children struggled to stomach his faith. They made me doubt that I’d want any books he left behind.

I also suspected that he’d hate that I had them. While I’ve spent most of my adult life writing and researching the intersections of literature and religion, I’m also a queer academic with a chip on their shoulder about religion and gender. I probably pray like a woman. I certainly enjoy lipstick and the occasional mix-gendered swim. When I engage with religious texts, I primarily do so as a literary critic. I look to analyze and understand the aesthetic, cultural, or political work of texts: what are they trying to say and why as opposed to what Truths can they give us. And while a spiteful part of me quietly relished the idea of some of this man’s books ending up in my possession, I also didn’t necessarily want them in my space.

The books were being kept in my grandmother’s detached garage. About five years prior, a pipe had burst and although the water had been shut off, the garage had been left to decay. When my grandmother had last gone to check on Pamp’s books (following an incident in which she’d tried to shoot a possum and left buckshot buried in the garage walls), she’d noticed mold spores. And so, the day after the cemetery visit, we trudged up to the garage to look at Pamp’s collection.

There wasn’t much to it. There were some twenty books in total, thick and hardback with gilded lettering, comprising three series covering basic religious topics. Two of the series seemed to have never been used. The spines weren’t broken, and they had a late publishing date, only a decade or so before Pamp’s death. “These probably aren’t worth holding onto,” I told Gran with some relief. “I’m not sure Pamp ever even opened them.” The other series, however, caught my attention: The Greater Men and Women of the Bible.

Published serially from 1913 to 1916 by Scribner’s and edited by Rev. James Hastings, an influential biblical scholar and renowned Scottish preacher of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Greater Men and Women consists of six volumes that encompass three-thousand-plus pages detailing the life and historical contexts of major scriptural figures. Organized chronologically beginning with Adam and ending with Titus, the preface states its purpose: “…to make the preaching of the present day accurate and attractive.” This makes it emblematic of a form of theological writing that dates as far back as the Middle Ages known as the preaching manual.

In many ways the work of the preaching manual is that of bridging the gap between past and present. In the case of Greater Men and Women, entries for each of the biblical characters seek to maintain a balance between approachability and historical analysis, pairing narrative description with historicist explanation. These entries work to make legible the logic of the biblical past to its modern readers. They explain the theological or historical significance behind biblical stories so that the studying preacher can extend that knowledge to his congregation. In the process, Hastings not only explains the historical strangeness of the biblical past, but (inevitably) imbues it with the ideologies of the present. Hastings wrote orientalist critiques of decadence into the legend of Solomon and instilled the story of David with a distinctly protestant praise of work ethic.

Unlike the others, this set of volumes had clearly been a frequent reference. While well cared for despite being more than a century old, the books hold signs of regular use: the edges are well-thumbed, the spines loose, and certain entries bear handwritten notes. Intrigued—and quietly hopeful that some marginalia might confirm the rumor that Pamp was a snake handler—I agreed to take them home.

At this point, I feel I should warn you: there are no dark family secrets hidden in the pages, no detailed explanations of Pamp’s life or theology, no telling doodles of snakes. A part of me, the chip on the shoulder part, had both feared and wanted to find misogynist annotations around the entries for Eve or Bathsheba or Mary. The closest I got was a bit of careful underlining under the entry for Jezebel: —“Jezebel was a woman of superior mind”—“under the fanatical care of Jezebel”—“Her influence over the king became only too great.”

Most of the marginalia were innocuous: reminders that Joshua was a soldier, a lopsided circle around a history of leprosy, a note that Solomon’s downfall was because he was “taking it easy.” Where Pamp seemed to have spent most of his time and energy was in the entry for Job. His thoughts on the question “Why do good people suffer?” were lengthy enough that they spilled over multiple margins. He had even added an appendix to the back cover in which he wrote out a list of six reasons:

1=Taxes for crime

2=Insurance higher because of drunkeness and theifs

3=Desease

4=Cross with Satan and World.

5=Perfection

6=Rom. 8: Suff[er]ing of this world not worthy to be compared with glory to be re[veil]ed

It wasn’t much to go on in terms of understanding Pamp. To be honest, I wasn’t sure that was what I wanted. Did I want to understand someone who thought of suffering in terms of insurance and taxation?

At the start of the series, Hastings includes a note that seems both warning and invitation: “[In the writing of this book] [c]riticism is kept subordinate to construction, as it should always be in the pulpit, but the work of the critic is not forgotten any more than that of the discoverer.” The critic and discoverer to which Hastings refers is different than what I embody. Hasting’s critic is the historical theologian who tries to make sense of biblical history; Hasting’s discoverer is the beginner encountering scripture in a sermon. In reading Pamp’s books, however, I found myself strangely transposed. I occupied both the position of literary critic working to understand century-old biblical exegesis and that of discoverer of a forgotten family text.

The critic and the discoverer, Hastings assures his readers, have not been forgotten in his work. Even though I know he didn’t mean—couldn’t mean—me, reading that in these roles I was not forgotten left me both uneasy and relieved. Uneasy in the sense that maybe (definitely) I wanted to be forgotten by a family history that marked Jezebel’s superior mind as a threat or that equated suffering with taxation. Relieved in the sense that I have the nagging, persistent worry that my history is being erased.

I mean that I feel that I cannot lay claim to it. I know that I hoard family secrets because I fear that somewhere in my recent past I have moved too far from my multi-generation, Appalachian roots, and they’re no longer possible to think of as mine. I watch narratives of Appalachia be constantly appropriated by books, politicians, even my own family members—eager to lay claim to the struggles of Appalachians as far as they stand in for the quintessential working-class white American. I feel my history being co-opted and myself erased because my life doesn’t fit: no charming stories of meth addiction, no parables about pulling myself from abject poverty. I have no interest in these narratives with their bootstraps and poverty porn. All I want are ghost stories and gossip. And I worry that these aren’t enough narrative, aren’t the right narratives.

I’m not entirely sure what I’ll do with Pamp’s books. I can’t imagine wanting to read them, but I can’t compel myself to throw them out. When leafing through them the other day, I came across a piece of family history, a forgotten valentine. Slim, it was tucked into the entry on Abraham, shortly before the account of his attempted sacrifice of his son Isaac. Printed on it is a bespectacled, smiling duck wearing a mortar cap and holding a book. The card proclaims: “A ducky Valentine…for someone very nice.” On the back in my grandmother’s handwriting is a note: “From Billy Nix.”

I called Gran to see if she had any gossip about Billy Nix or reading Greater Men and Women. “No, darlin’, I don’t,” she told me after a pause. “That’s long enough ago that it could have been anybody. To tell you the truth, while I remember looking through Pamp’s books, I don’t remember much about what was in them. Didn’t seem like there was much there for me.”

I don’t know that there’s much there for me either. But I can’t get rid of them. And so, I hold onto them, lodged carefully next to Solzhenitsyn, Rand, and (because I couldn’t resist) Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit. They feel like a version of cemetery flowers, a means of providing care for a history that I may not rest easy with, but which I don’t want to forget or be forgotten by.