Picasso’s Tears

Picasso’s Tears

Wong May

Octopus Books, June 2014

323 Pages

$24

Buy: book

Few books of poetry this year will have a more interesting back story than this one. Born in China in 1944 and raised in Singapore, Wong May came to the United States in the 1960s to attend the Iowa Writers Workshop. Between 1969 and 1978, she published three collections of poetry with Harcourt Brace. Then, rather abruptly, no further books.

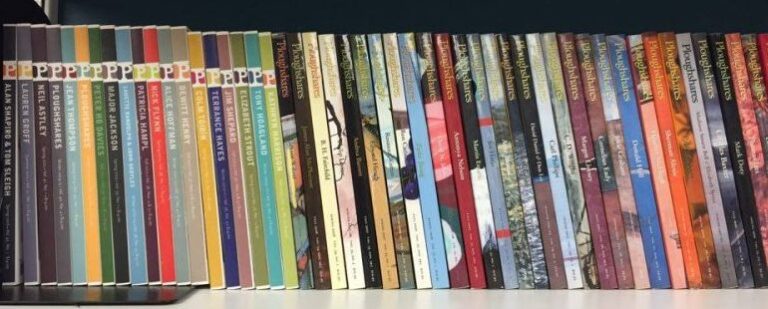

Poet Zachary Schomburg came across Wong May’s first book, A Bad Girl’s Book of Animals, in an Akron public library and was sufficiently intrigued to investigate. It turned out than Wong May had married an Irish physicist, moved to Dublin, and raised two sons. Although she published virtually nothing, she had continued to write poetry. Since Schomburg is one of the many contemporary poets who has a sideline as an independent publisher, we now have Picasso’s Tears, a handsomely-designed (by Drew Scott Swenhaugen) hardbound volume, 286 pages of poetry and an interview (more precisely, a 12-page answer to the question, “How has your relationship to poetry changed since 1978?”).

The poems, as one might guess from work from so long a span, work in many different ways. They sometimes have a narrative (“Mozart”), or the skeleton of a narrative (“Tarpaulin”), but they are sometimes just a vanishing presence, unseizable as smoke (“Spanish Baroque”). They are aware of tradition (alluding to, for example, Milton, Blake, Keats, Pound, and Williams) but observe a logic of their own. They sometimes crystallize into propositions–“Quite possibly we forget all / Damn-well-all but the fleeting”; “America how you have grown old in the new century”–but they are equally at home in enigma:

If younger I have missed you

in the long field

Where all was fierce and jubilant

–there’s panic

Panic and no pain in youth.

Younger I could not have missed you.

The poems are at once reticent and generous. We learn nothing very specific about Wong May from them, yet their interiority is so powerful that we feel we know a great deal about, for instance, her relationship with her mother, however scarce the details.

The volume’s biggest risk is a long poem (almost seventy pages), “The Making of Guernica.” Its premise, a parallel between the infamous air raid that became a famous painting and the Boston Marathon bombing, seems unsustainable. Both occurred in April, yes, both targeted civilians, but can anything be made of that? Somehow, by the time the poem begins addressing the Statue of Liberty, whose torch unites her to the woman with the oil lamp in Picasso’s painting–or perhaps it is when the Taliban-dynamited Buddha of Bamiyan is described as “2 vast trunkless legs of stone,” evoking Shelley’s Ozymandias, or when the poem begins to address “Zachary” about its own impossibility–something is made, and Wong May’s attempt to use her art to understand suffering begins to make the kind of sense that Picasso’s does.

It would be rash to predict for Wong May the kind of belated but deep and widespread recognition that eventually arrived for Lorine Niedecker; were such recognition to arrive, though, it would be merited.