Police Violence & Street Art

It is not often that poetry goes viral on the internet, but that’s what happened last month with a poetry project in Boston, Massachusetts. MassPoetry.Org and the City of Boston have teamed up to introduce poetry into the streets of the city via a water-repellant spray that reveals poems on the sidewalks when it rains. Their artist statement echoes a truly Situationist sentiment: “With Raining Poetry, we are able to bring more poetry into the everyday lives of the unsuspecting.”[1]

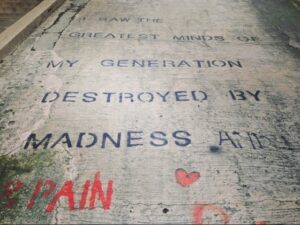

What I love about this project is that it intersects poetry with the street in a manner that makes the two subjects more visible. Street art and poetry have both had a long relationship with social justice, which makes this particular collaboration so relevant. As poet Major Jackson says, “one of poetry’s chief aims is to illumine the walls of mystery, the inscrutable, the unsayable.”[2] The presence of these poems in the street, then, both illumines the unsayable but also illumines this space some often take for granted: the street.

American streets are not inextricable from commerce, as they are the main thoroughfares for circulation that bring us to and from work, to and from businesses, to and from city centers. So the sudden appearance of poetry in the streets does a lot to draw our attention to the street as not just a space of circulation but as a space that has been constructed by bodies for other bodies. We stop and stand, feet on concrete, and read, and perhaps our attentiveness to language and ideas in these moments will grant us an ability to see our streets more clearly for their materiality and purpose. As this hopeful message up at former world famous street art destination 5 Pointz reminds us, “A.R.T.S. stands for Art Rules The Streets.”

The Raining Poetry project is of course not the first attempt to get language into city spaces. Graffiti writing was born largely out of hip-hop culture in New York City. As the narrator of the 1983 documentary Style Wars introduces it, “[Graffiti writers] call themselves ‘writers’ because that’s what they do. They write their names, among other things, everywhere—names they’ve been given or have chosen for themselves. Most of all, they write in and on subway trains which carry their names from one end of the city to the other. It’s called, ‘bombing,’ and it has equally assertive counterparts in rap music and break dancing.”

Cities across the world are filled with graffiti and street art that speak in a variety of registers toward a slew of subjects. One of the stranger instances of a long running project of putting language into streets are the Toynbee tiles, the creator(s) of which remain as much of a mystery as the tile messages themselves.

Poetry Society of America similarly works to introduce poetry into the flow of daily life with their Poetry In Motion project, “helping to create a national readership for both emerging and established poets.”[3] And writer/book artist Emily Dyer Barker from Salt Lake City has for years involved the public in a variety of projects that mix broadsides and letterpress with storytelling and QR codes. She calls them “public spectacle essays” and she employs friends, acquaintances, and strangers in posting the broadsides in their respective cities.[4]

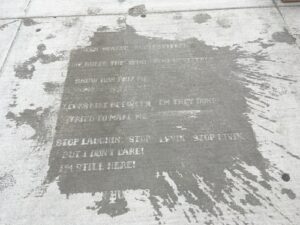

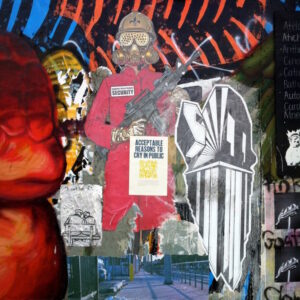

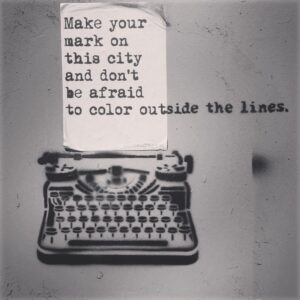

I’ve encountered non-city sanctioned language in cities around the world, some of which push a more political message, some of which provide reminders seemingly aimed at whatever single individual passes them and takes notice. Here are a few of my favorites:

[Top to bottom: Los Angeles, California; Buenos Aires, Argentina; Sliema, Malta]

Street artists and graffiti writers, then, show us the contours and reveal to us the politics of public space by utilizing that space’s material attributes to draw attention to how we inhabit our surroundings. Critic Susan Stewart writes in her essay, “Ceci Tuera Cela: Graffiti as Crime and Art:” “[Graffiti w]riters do not conceive of their role as one within a larger narrative or historical structure other than this specific tradition of graffiti writing; rather, they place their arts within the interruptions of social life, marking off a physical space for a time…”[5]

American streets, though, are also never inextricable from the violence that happens in them, whether that’s the violence of street harassment or the violence of an overly militarized police state. Just last month, Tamir Rice would have turned 14 years old if he hadn’t been shot dead by police in the streets of his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio two years prior. This past week in the U.S., two black men were murdered by police officers. Alton Sterling was murdered for selling CD’s outside a store in Baton Rouge. Philando Castile was murdered in his own vehicle next to his girlfriend and her small child during a traffic stop in Falcon Heights, Minnesota. The sooner we can make the streets visible, perhaps the sooner we can make what happens in the streets visible to those in America otherwise unwilling to acknowledge the violence of the street: police shootings, manipulative urban planning, gentrification, and the further oppression of communities of color.

So while street art and projects like Raining Poetry deliver us a sense of awe, they will hopefully also cause us to consider who the streets are for, who these messages are for, who gets to stand on a sidewalk, any sidewalk, and feel safe, and who does not have that privilege. I know this is a heavy call to action for a project that is trying to counter the mundane act of walking with the miracle of a poem, but I hope it can also serve as a reminder to the more privileged among us that walking isn’t mundane for everyone and that not all bodies can move through streets the same.

Fortunately, because we all inhabit the streets in one way or another, we can use them to speak anonymously those messages we want others to hear. Streets can be a space for art and poems but they have also always been a space for graffiti writers to claim their identities and for the public to make themselves seen. Language on its own can be powerful, but a language that calls out from the very materials of our everyday lives might be able to speak into certain silences to effect change.

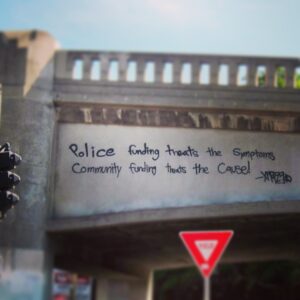

[Top to bottom: “Please hire teachers of color,” outside Ithaca High School, Ithaca, NY {photograph from poet Lillian-Yvonne Bertram}; “Police funding treats the symptoms/Community funding treats the cause!” Downtown Los Angeles, CA]

[1] http://www.masspoetry.org/rainingpoetry

[2] http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/articles/detail/68755

[3] https://www.poetrysociety.org/psa/poetry/poetry_in_motion/

[4] http://www.acceptablereasonstocryinpublic.com/

[5] Stewart, Susan. “Ceci Tuera Cela: Graffiti as Crime and Art.” Crimes of Writing: Problems in the Containment of Representation. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 1994.