Review: THIS IS WHY I CAME by Mary Rakow

This is Why I Came

Mary Rakow

Counterpoint, December 15 2015

204 pp; $24

Buy | eBook

To tell you that Mary Rakow’s lyrical novel This is Why I Came is a recasting of biblical narratives hardly sets the book apart—the Bible, with its knotty metaphors, unequaled cast of complex characters, ebullient wisdom, and dense moral inquiry has, for better or worse, shaped the history of literature (there are more than a thousand biblical references in the works of Shakespeare alone). Rather, what makes Rakow’s novel immediately distinctive is its scope. The more common approach to engaging with biblical texts seems to be this: extract a compelling slice of ancient scripture and sound its depths through either analysis or imagination. Examples close at hand, each published this fall, include Pulitzer-prize winner Geraldine Brooks’ novel The Secret Chord, which newly envisions the life of King David, and The Good Book: Writers Reflect on Favorite Bible Passages, an anthology featuring contributors such as Edwidge Danticat, Lydia Davis, and Tobias Wolff. While these works zoom in and complicate, Rakow’s slim novel, released this month from Counterpoint Press, pans outward to consider the Bible entire.

In elegant prose and fable-like fragments, This is Why I Came reimagines specific stations from the biblical saga in a way that illuminates causality and humanizes the ancient Hebrew and Greek tales. Such an approach might seem akin to the likes of Thomas Jefferson’s famous version of the Gospels, in which the miracles are redacted and the teachings retained. Yet the novel is not weighted by a sense of utility, and though Rakow holds a Ph.D. in theology, it is likewise far removed from academic allegory. Instead, This Is Why I Came is a powerful reckoning with the tension between faith and doubt, suffering and salvation. It is a restless inquiry, a wondering that gracefully swoops between anger and awe. From the novel’s mosaic structure arises a central question: How are we to dredge mercy and meaning from unspeakable violence, and endure the sorrow that is left in its wake? Surely and sadly, this question remains as pressing now as it was in antiquity.

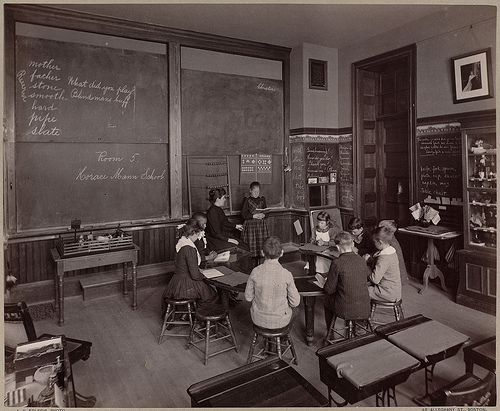

Taking its design from the Bible, Rakow’s novel contains a book within a book. The narrative opens in present day, when a woman attends church on Good Friday for the first time in over thirty years. While awaiting her turn in the confessional, she removes from her purse a hand-bound manuscript with ragged pages, “a Bible of her own, a testament where she could cast a thread through the silence.” The contents of her creation form the bulk of This is Why I Came.

Thoughtfully distilled, the chapters that follow alternate between figures that many will find familiar: Adam, Cain, Moses, Mary (both Magdalene and Mother), Jonah, and Joseph, among others. Rakow paints the violent events that touch these characters’ lives in broad strokes, then stays with them, charting the repercussions with resounding compassion. First, the near-sacrifice of Isaac, Abraham’s hand stayed in the novel not by the appearance of a ram but by the anger of his wife, Sarah. Then, the catastrophic flood described in Genesis. While in the Bible Noah never speaks, in Rakow’s telling he openly struggles to align the obliteration of the world with his sense of the divine:

“When the dog floated by, Noah said to himself, love is stronger than this. And he clung to that one sentence as to a plank floating on the water, a single plank, repeating it to himself again and again.”

Jonah is likewise besieged by pain when he observes the wrath of God. Though this prompts him to profess disbelief, he ends up at something closer to acute disappointment. Foreseeing a future in which his ambivalence will be incorrectly portrayed, Jonah can only wish that

“those who would devoutly paint him would give him truer words, more his own, so that the scroll would read, simply, ‘I wanted a better God.’”

These scenes from the Old Testament foreshadow further tragedy in the second half of the novel. In chapters detailing the Annunciation, Mary confronts the harrowing task of convincing Joseph of the nature of her pregnancy. The Nativity is likewise cast in grim shadow, with King Herod’s infanticide brought to the fore. Grief-stricken, the community is ruthless, emphasizing the link between Jesus’ arrival and the slaying of their firstborn sons—the women of Bethlehem deny Mary access to the well, while customers boycott Joseph’s shop; eventually, he flees to Galilee. “What is the price of salvation?” Mary later asks the adolescent Jesus, to which he replies, “Death.”

Importantly, This is Why I Came is as tonally broad as it is temporally ambitious. Interspersed by these scenes of staggering violence, transgression, and cruelty are answering moments of nobility, kindness, and passion. Thus in the way of life itself, the novel demonstrates how beauty and brutality can at times be impossible to disentangle. As an adult, Jesus gains valuable insight from those that he heals: from Legion, the power of touch; from the blind man, the exponential force of love. After Jesus’ death, the characters are caught in stunning moments of intimacy as they consider what they lived to witness. Old and alone, Mary contemplates how her son’s legacy will be preserved. “What survives?” she wonders, and despite unfathomable sorrow, reasons on the sweetest aspects of existence: “Love and the memory of grapes.”

The God in Rakow’s novel is just as questioning and capacious as those over whom He wields power. Often dissatisfied, His problems are human-sized, familiar: desire, doubt, vanity. He is a God who rages, repents. Perhaps most affecting is the difficulty with which He forgives—far from a genie-like granting or uncomplicated imperative, God’s mercy is wrung from His depths in a grand pageant of inner struggle. Yet despite these poignant glimpses of character, the God in Rakow’s novel is ultimately a figure misremembered, or perhaps never known at all. He is at once cast as real and as a human concept, reduced by attempts at definition—in the novel, it is Adam who thinks of the word “God.” When Moses requests to see God’s face, he is denied with the warning that doing so would cause death. Later that night, Moses stares up at the inky heavens and sees “each star [as] an opening.” He hears God’s voice: “Come to me. I have given you infinite doors.”

Some readers might be uncomfortable with Rakow’s unconventional take on stories that can be held as impervious, sacred. Others might be dissatisfied with the novel’s fleet pacing, its prose poems romping past large swaths of material in a way that can feel over-simplified. This is Why I Came offers no fixed position on God, no easy reconcilability. Yet it is precisely these qualities that allow the small book to contain myriads. The sense of faith that resides within its pages is sharpened by a residue of doubt, reserving the greatest reverence for that which can never be neatly pinned down.

“The actual theological meaning of the word ‘salvation’ is meaning,” writes Fanny Howe in her essay “Bewilderment,” in which she discusses the ethics of choosing perpetual curiosity over certainty. “To seek salvation is to seek a sense of meaning to the world, one’s life,” she adds. In just such a way, This is Why I Came is made salvific by its searching; rather than confronting the fact of human suffering with assertions of light, the novel voyages further into the darkness of essential mystery. Resistant to crystalline denouement and wary of firm answers, it beautifully bares the ragged edges of uncertainty. In cracking open ancient texts and considering them anew, Rakow insists on the value in still grappling with those ageless, unresolvable matters—questions of where we came from, and why, and how we might be now that we are here.