Beyond Sympathy: Seeing Myself in Viet Thanh Nguyen’s THE SYMPATHIZER

When I was growing up in the 80s there was significantly less talk than today about diversity in literature. Jacqueline Woodson, author of the National Book Award-winning Brown Girl Dreaming, stresses the need for recognition of whole populations, for readers to see mirrors of themselves in books, especially young readers. It is important “to see that the people who wrote the books look like them, so that they can understand their own power and ability.”

I found and reconstructed parts of myself in literature through composition and approximation. I was made up of fictional girls and boys who raced, read, kissed, relished first bites of apples, sold their hair to support their families, wrote skits to perform with siblings. They were bookish and sullen and jealous of older sisters, desperate for fathers to quit cigarettes. They sharpened spears, fended themselves against wild dogs, and ran away with little brothers to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They fought against domesticity, but helped with sewing and sugaring and sealing log cabins with pitch.

It never occurred to me to search or even wish for a narrative about a Vietnamese girl living in the United States. I was grateful for vague glimpses of difference and likeness I found here and there — the Chinese girl exploring Brooklyn, the Cambodian girl who’d escaped the Khmer Rouge, the artsy Japanese American babysitter — but I don’t remember thinking it possible to fully locate myself. Maybe what I had found seemed enough, or maybe I believed I couldn’t ask for more. My family’s process of adapting to this new culture was mostly guesswork so I was in the custom of not asking, only making sense of and building from what I’d found or was given to me. Perhaps with books it wasn’t a matter of trouble finding so much as not grasping what or who was missing.

Reading for me has never been just a transporting fantasy; what I seek is entry into the mind and experience of another person. This is why I love essays. So what I could not cultivate though seeing myself represented I made up for with some sort of universalist empathy, feeding myself with varying forms of connection no matter how different the voice or writer. I could always readily imagine being someone else. Only as an adult am I mourning the absence of stories that might have made me believe with confidence I could grow up and become the person and writer I am today, as Woodson suggests.

Finally in college I began finding Vietnamese writers who wrote Vietnamese characters: Monique Truong, Lan Cao, Bich Minh Nguyen, Aimee Phan, Linh Dinh, Andrew Lam, and Nam Le. There are more now: Hieu Minh Nguyen, Cathy Linh Che, Vi Khi Kao, Ocean Vuong, VT Hung, Jenna Le, etc. Their voices and stories sink into my bones and fortify me.

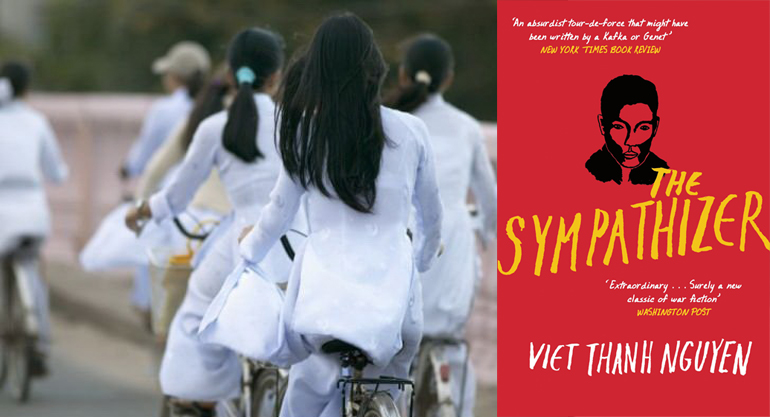

Now more than ever I’m celebrating this, having recently read the Pulitzer prize-winning novel, The Sympathizer, by Viet Thanh Nguyen. Here is something new. Here I am feeling for the first time how profoundly sustaining and validating it is to recognize not only myself but also my culture in literature.

The Sympathizer isn’t about a Vietnamese girl or woman living in the U.S., but it touches something more profound, the fundamental part of me, that extends deeper and earlier than my arrival to this country. Like Nguyen, I was born in Saigon, but well after the war. Leaving at five years old, I never got to know my birth country, and my family doesn’t talk about the war. Nguyen has given me what I didn’t know but always felt quite directly of the roots of family and the history of war. Though I was born after the central event of his novel—the Vietnam War—it is also my story.

I belong to a clan of loud, street-smart, poetic, foul-mouthed, double-punning religious hustling romantic fatalists. We Vietnamese do things other peoples don’t and don’t do things others do. Nguyen captures these nuances of Vietnamese customs and quirks so precisely in The Sympathizer. I imagine it’s the way black American readers see their humanity in James Baldwin’s John Grimes of Go Tell It On a Mountain and Toni Morrison’s Pecola of The Bluest Eye; Native Americans in Sherman Alexie’s many narrators and Natalie Diaz’s brother of When My Brother was an Aztec; Chicanos in Sandra Cisneros’s Esperanza Cordero, Dagoberto Gilb’s Mickey Acuña, and Kirstin Valdez Quade’s voice; Dominican Americans in Junot Diaz’s Yunior and the García sisters of Julia Alvarez’s imagination.

But beyond being a seminal book in my reading life, the scope, skill, and honesty with which Nguyen penned The Sympathizer makes it an extraordinary novel, whatever your identification with it.

I share now some of the novel’s lines that struck me as stunningly familiar—scenes I’ve witnessed and lived, mannerisms and personalities I know well, jokes that only a Vietnamese person might fully appreciate. Yet, the experience was so jarring I had to re-read passages several times until the laughing and crying ceased and I could move on. For the first time, I recognized my father, mother, siblings, aunts and uncles—the country and people from where and whom I came.

And it feels so, so good.

She had a mind like an abacus, the spine of a drill inspector, and the body of a virgin even after five children…She was, in short, the ideal Vietnamese woman.

“We were not a people who charged into war at the beck and call of bugle or trumpet. No, we fought to the tunes of love songs, for we were the Italians of Asia.

“These passengers murmured among themselves, complaining of this and that, which I ignored. Even if they found themselves in Heaven, our countrymen would find occasion to remark that it was not as warm as Hell.

“…queuing was unnatural for our countrymen. Our proper mode in situations where demand was high and supply low was to elbow, jostle, crowd, and hustle, and, if all that failed, to bribe, flatter, exaggerate, and lie. I was uncertain whether these traits were genetic, deeply cultural, or simple a rapid evolutionary development. We had been forced to adapt to ten years of living in a bubble economy pumped up purely by American imports; three decades of on-again, off-again war, including the sawing in half of the country in ’54 by foreign magicians and the brief Japanese interregnum of World War II; and the previous century of avuncular French molestation.

“Oh, fish sauce! How we missed it, dear Aunt, how nothing tasted right without it, how we longed for the grand cru of Phu Quoc Island and its vats brimming with the finest vintage of pressed anchovies! This pungent liquid condiment of the darkest sepia hue was much denigrated by foreigners for its supposedly horrendous reek, lending new meaning to the phrase ‘there’s something fishy around here,’ for we were the fishy ones.

“The most distinctive thing about the vice president, besides his air of effortless distinction, was the Clark Gable mustache playing dead on his upper lip, an adornment favored by southern men who fancied themselves debonair playboys.

“In those days, her name was still Lan and she wore the most modest of clothing, the schoolgirl’s ao dai that had sent many a Western writer into near-pederastic fantasies about the nubile bodies whose every curve was revealed without displaying an inch of flesh except above the neck and below the cuffs.

“Besides the simple yet elegant cha-cha, the twist was the favorite dance of the southern people, requiring as it did no coordination.

“Like most of us Vietnamese men, he simply did not want to be even brushed with domesticity.

“Wherever we found ourselves, we found each other, small clans gathering in basements, in churches, in backyards on the weekends, at beaches where we brought our own food and drink in grocery bags rather than buying from the more expensive concessions.

“Their afflicted kids were talking back, not in their native language, but in a foreign tongue they were mastering faster than their fathers. As for the wives, most had been forced to find jobs, and in doing so had been transformed from the winsome lotuses the men remembered them to be.

“But out of deference to our hosts we kept our feelings to ourselves, sitting close to one another on prickly sofas and scratchy carpets, our knees touching under crowded kitchen tables on which sat crenellated ashtrays measuring time’s passage with the accumulation of ashes, chewing on dried squid and the cud of remembrance until our jaws ached, trading stories heard second- and thirdhand about our scattered countrymen.

—Viet Thanh Nguyen, The Sympathizer (2015)

The gift of literature is to live experiences and view perspectives different from our own. I’ve read and pieced myself together from so many different characters all my life, earning an education in sympathy and empathy alone. But now more and more people like myself are finally starting to see ourselves come into focus. May we continue writing and reading literature that affirms and challenges us all. And let us be kind.