The Ambiguous Epiphany

When I was a child growing up Catholic, the Feast of the Epiphany struck me as an afterthought. December was all about the thrilling run-up of Advent, characterized by candle lighting and singing at mass and by lists for Santa and chocolate-filled calendars at home. Finally there was the tremendous climax of Christmas. Jesus is born! Santa is here!

When I was a child growing up Catholic, the Feast of the Epiphany struck me as an afterthought. December was all about the thrilling run-up of Advent, characterized by candle lighting and singing at mass and by lists for Santa and chocolate-filled calendars at home. Finally there was the tremendous climax of Christmas. Jesus is born! Santa is here!

After that, it was all denouement. Epiphany was when our Christmas tree—by then shedding needles at an alarming rate—finally hit the curb. It was also the last little burst of festivity at church before the long stretch of Ordinary Time. The three wise men had made it to Bethlehem. My mother or maybe a priest explained that in many cultures, Christians waited until the Epiphany on January 6 (also known as Little Christmas, Twelfth Night, and the Twelfth Day of Christmas) to exchange gifts. This was mildly interesting, but I wouldn’t be getting any more gifts, so it was hard to get too excited.

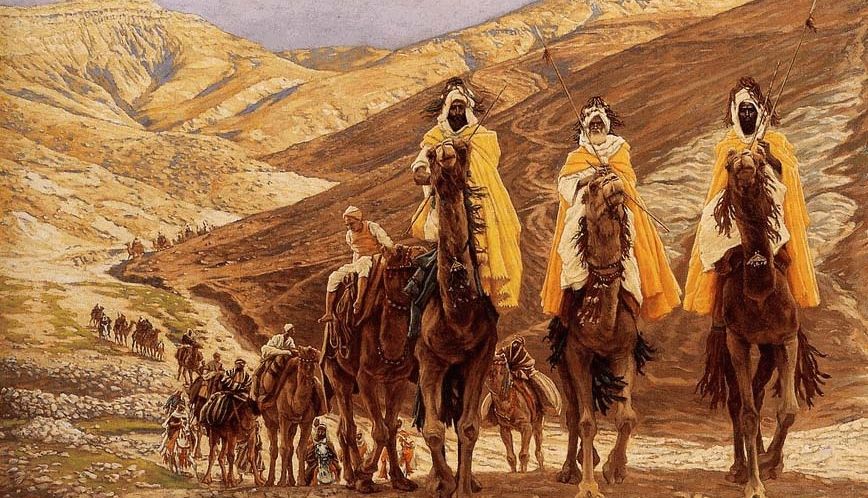

Now that I’m a lapsed Catholic fiction writer who still loves Christmas, I’m trying to figure out what stories to tell my kids about this season. I keep coming back to the Epiphany, which seems to me now fantastic and magical, a journey fraught with hardship and intrigue and faith and even espionage. When the Magi arrive in Jerusalem and ask King Herod, “Where is the infant king of the Jews?”, he is disturbed and sends them on to Bethlehem with instructions to report back when they find the baby. But after they meet the infant they’re warned in a dream not to return to Herod. They instead follow a different route back home. Herod intends to kill the baby, who he sees as a rival.

The entire story of the wise men runs about five-hundred words and is only conveyed in Matthew’s gospel, but the event represents the revelation of Jesus’s divinity to Gentiles. “The sight of the star filled them with delight, and going into the house they saw the child with his mother Mary, and falling to their knees they did him homage.” This moment ushered in enormous change, and many a creative writer has been inspired to retell the story.

James Joyce, who famously broke with Catholicism but certainly never shook it, introduced the literary concept of the epiphany. Robert Scholes and A. Walton Lutz, the editors of the Viking Critical edition of Dubliners (1969), discuss his use of the term in a background essay, “Epiphanies and Epicleti.” They point to a passage from Stephen Hero, an early draft of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man:

By an epiphany he meant a sudden spiritual manifestation, whether in the vulgarity of speech or of gesture or in a memorable phase of the mind itself. He believed that it was for the man of letters to record these epiphanies with extreme care, seeing that they themselves are the most delicate and evanescent of moments.

Scholes and Lutz also quote Joyce’s explanation to his brother:

[T]here is a certain resemblance between the mystery of the mass and what I am trying to do . . . to give people a kind of intellectual pleasure or spiritual enjoyment by converting the bread of everyday life into something that has a permanent artistic life of its own . . . for their mental, moral and spiritual uplift.

“The Dead,” the final story in Dubliners, begins at a party during the Christmas season, likely for the occasion of the Epiphany. The protagonist is Gabriel, and his aunts throw the party annually. At the end of the party, he notices his wife listening to a song with great attention and remembers the early stages of their romance. By the time they arrive at their hotel room, he’s filled with desire for her but at a loss as to how to make advances. He coaxes her to tell him what she’s thinking about, and finally she admits that the song she heard earlier reminded her of a boy named Michael Furey who loved her and died of consumption after venturing out in the rain and cold to see her. Gabriel feels foolish. “While he had been full of memories of their secret life together, full of tenderness and joy and desire, she had been comparing him in her mind with another.”

His wife cries herself to sleep, and Gabriel thinks back on the evening, to his own foolishness and to his elderly aunts, who he knows will die soon. He realizes he’s never felt toward any woman the kind of love the dead boy felt for his wife.

It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thrones. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

My edition of Dubliners contains five essays on “The Dead” and I’ve read them all. Each critic delves authoritatively into the symbols at work in this final vision, often interpreting them differently, and even coming to different conclusions about whether this is fundamentally an up or a down ending. I like reading this kind of analysis, and I have a favorite essay and interpretation, but since I aspire to write fiction, I think it’s also important not to lose sight of my own feelings during the journey of the story.

My journey, then: disgust for Gabriel’s self-satisfaction and pretensions throughout the party, nosy interest in his sudden lust for his wife, sympathetic embarrassment when he realizes he’s misread her feelings entirely, which gives way to apprehension of the unknowable depths of even the people he is (I am!) closest to. Finally, I was pulled with him into the image of snow blanketing Ireland and felt connected to something vast and unknowable, beautiful but not entirely benevolent.

It’s intimidating to approach “The Dead,” which has been so widely studied that it’s easy to fear I’m reading it wrong. I might be. But I could luxuriate for quite a while in the ambiguity of its epiphany. Does it point in the direction of life or death? Hope or despair? Does there have to be an “or”?

In his 1927 poem “Journey of the Magi,” T.S. Eliot explores the ambiguity of the Christian Epiphany, from the perspective of one of the wise men.

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

Like Gabriel, once this narrator has seen what he’s seen, he can’t return to the way things were before. Disruption of this magnitude is a kind of birth and a kind of death.

Image: The Journey of the Magi (James Tissot, 1894)