The Last Love Poem I Will Ever Write by Gregory Orr

The Last Love Poem I Will Ever Write

Gregory Orr | June 11th, 2019

Viking/Penguin Books

Amazon

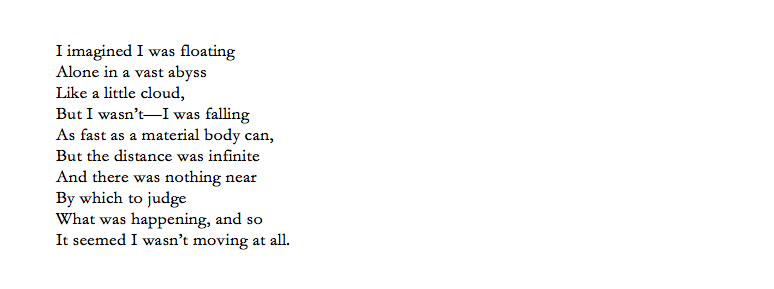

The Last Love Poem I Will Ever Write, Gregory Orr’s twelfth collection of poetry, has the whiff of finality its title suggests. The book begins, as Orr’s life began, with the death of his brother, whom Orr accidentally shot and killed when they were children. It moves from that grief and the existential doubt it prompts into poems about writing, politics, and love, posing that early grief as the foundation of all other emotional textures within the speaker’s life. In the first poem, “And So,” the speaker says that in the days after his brother’s death he “knew/God and [he] were through,/And after that, what is there?” The collection begins in sorrow and bafflement and then abandons it, distracted by the material of the speaker’s life as it extends away from that initial incident. This movement seems, in itself, like an attempt to answer that question: after disaster, what remains? After the last love poem you can write to your living brother, or to God, there is something. The last lines of this first poem reinforce this:

Though the speaker feels alone, his perspective is distorted by grief. Though knowing you’re falling is terrifying, it is a sort of comfort to know that falling means the earth still exists below you.

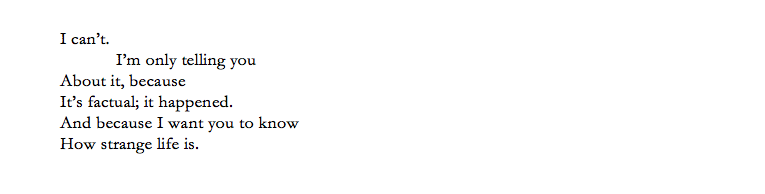

Though the speaker isn’t loosed from the earth, as his brother has been, he is loosed from his faith, and the next poems of the collection are largely trying to reckon with the idea of a god who has allowed the tragedy of his brother’s death to happen. Could a god allow it? The accident that killed his brother is a reproduction of his own father killing his best friend by accidentally shooting him. “I’m telling you it’s true,” says Orr in “Song of What Happens,”

Of course, the question is impossible to answer because there is no benevolent god that would plan for a child to kill another. “I’m happy for you if you/Can explain it/To your satisfaction,” says Orr.

These last lines of the poem indicate the meaning Orr has been able to make of this event—that there is no meaning, that things happen for no reason at all and, as he says later in the poem “Dark Song,” “the world/Suddenly turns ugly/And decides to crush you” without any real warning. “Don’t waste time trying/To understand, just fight/For your life,” he advises. In the long poem “Ode to Nothing,” that meaninglessness, which is threatening in “Dark Song,” becomes redemptive, which Orr celebrates. Part one begins,

Nothing, here, becomes tactile or takes up space. The poem asserts both that there is not a thing holding the universe together—it’s not held together at all—and that nothing is the thing that actually does hold it. Nothing becomes a religion, lives within our bodies, presses in on us from space. How natural nothing becomes, by the end of this poem. “So many people I loved/ Are now a part of nothing,” Orr says.

The doubleness of nothing in Orr’s usage of the word makes the idea that you will be forgotten after death natural. There is a place for you, in nothingness, after your death, when nothing on Earth “cares for you” anymore. Orr refuses to allow the reader trite comfort here—and instead finds it in the emptiness he expects after death. That emptiness is both problem and solution here. It is the grief that makes the speaker who he is.

These poems of grief and doubt are the strongest in the collection. There’s much to be admired in the poems that follow them—they are the affirmation of life and love that the doubt that begins the book asks for—but they don’t consistently have the power of the poems that begin the book. The kernel of grief that sets the speaker on his course, and which seems to fascinate him across time, is also what fascinates us. The crystalized, perfectly-clear articulations of grief that begin the collection ring through it, though, making it impossible to read even the simplest lyric in The Last Love Poem I Will Ever Write as light.