The Physics of Poetry or the Poetry of Physics

When I started my Google search with the words “physics and poetry” I did so with some reluctance, knowing that each time I clicked on a headline or hit the return key I was willfully handing over hours of time to the trailings of one of my recent curiosities. The most direct hit was Stephen Hawking reading a poem, called “Relativity,” dedicated to him by the poet Sarah Howe, as well as a piece she wrote for the Paris Review on the experience of writing the poem and then meeting Stephen Hawking. Another good match came in the form of a paper written by a physicist in California named Alberto Rojo that looks at poets throughout history who put into words the concepts that physicists theorize, and prove. He probably wrote it just for fun.

I found, and was offended by, an undergraduate course called “Physics for Poets” which aims to make physics easy to understand by removing the math. And then I learned that Jorge Luis Borges intuited and illustrated the theory of relativity in his stories and poems long before Einstein made it into the theory of physics that changed our understanding of the universe.

My favorite finding by far was something called “Quantum Sheep.” It seems there is a practice of writing random words on sheep’s behinds and then watching a poem form as they move about a field in a flock. As a bit of an aside, I was not surprised that many poets and physicists have linked the two disciplines, but when I learned of “Quantum Sheep” I wished the idea had been mine.

Two factors combined to launch me into this particular internet-mind wormhole. One is that I read an article in The Atlantic online this past fall called “The Case Against Reality.” The other is that I am a poet who, like most poets, enjoys the business of mind-altering. In “The Case Against Reality,” Amanda Gefter interviews the cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman. Hoffman is pretty sure that “the world presented to us by our perceptions is nothing like reality.” As a poet this seemed too good to be true.

I really wanted to believe Hoffman, so I read the interview and re-read it, and read it again, and also watched the handy little two-minute video embedded in the body of the text in which Hoffman explains with ease what his theorem is all about. Yes this was a commitment, but just like so many of the gems of contemporary poetry, trying to understand a cutting edge theory that combines neuroscience, evolution, and fundamental physics ought to involve some effort.

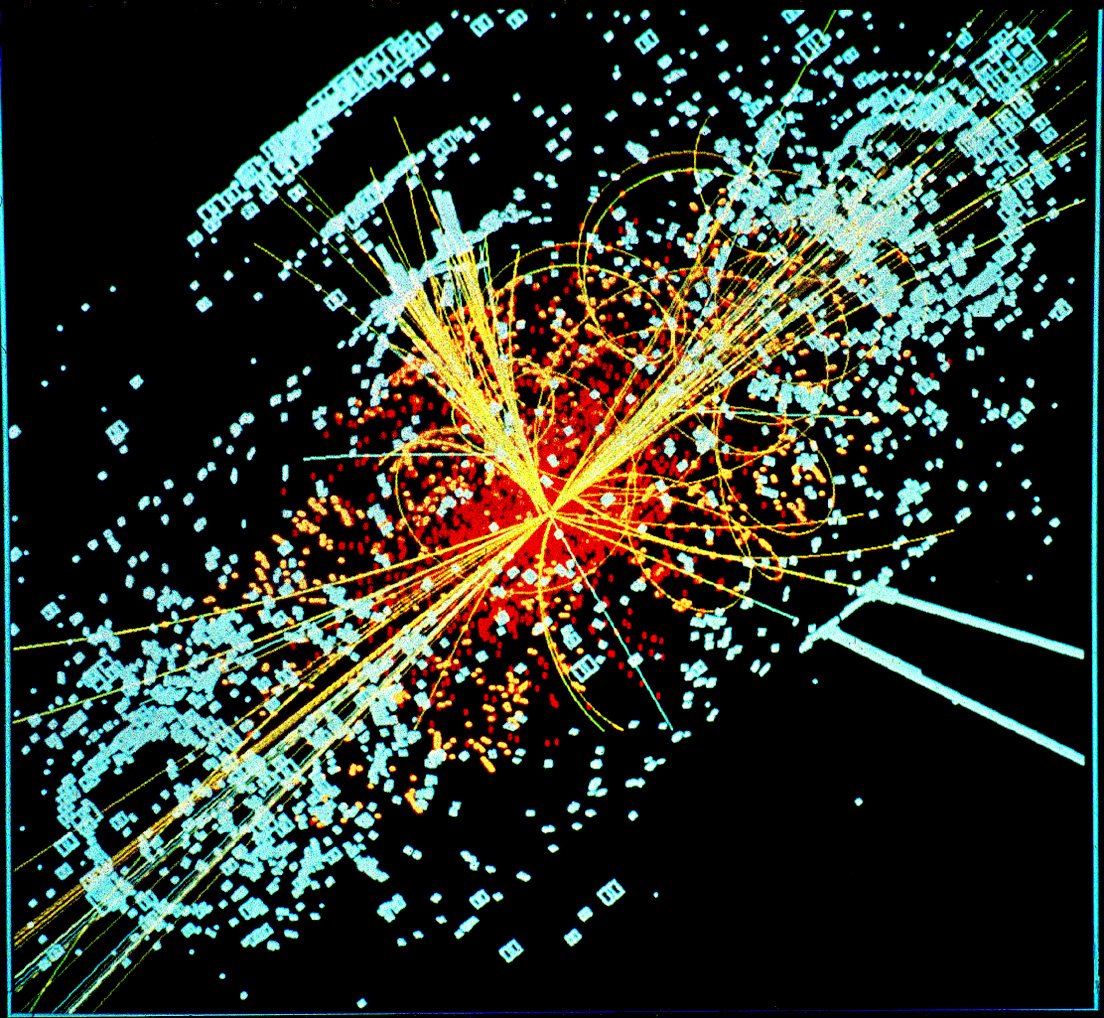

Hoffman says his theorem has been mathematically proven. It goes like this: “According to evolution by natural selection, an organism that sees reality as it is will never be more fit than an organism of equal complexity that sees none of reality but is just tuned to fitness.” The way I understand it, evolution hasn’t made our perception (or the perception of any species alive today) more keen in that we can see more of reality; seeing more of reality does not give us an evolutionary edge. Instead, reality is whatever it is (we have no idea; it’s literally too complicated for us to understand) and our tools of perception have evolved to show us only symbols or representations of the bits of reality that help us survive.

The best example Hoffman gives to illustrate his idea is a metaphor (yes, a metaphor!) of a desktop interface. Hoffman says, if you want to edit an essay on your computer you might click on a little blue folder on the desktop. Now is that little blue folder actually a folder that contains a sheet of paper that you can type on? Of course not, but this interface is a very useful representation of all the information and inner workings of a computer that allow you to write your essay. Reality is like that: it’s so much more than we need to know that actually being exposed to it would interfere with our ability to function.

Here we are seeing things, feeling things, talking, writing, painting, playing, thinking–yet we know that in the way we perceive the world, reality is actually being hidden from us. No wonder this stuff is so hard to figure out, no wonder we’re lost, no wonder Donald Trump, no wonder we write poetry. Applying quantum mechanics to evolution, Hoffman says: “[Y]ou have your own [perception of] headache, your own [perception of] moon. But I assume it’s relatively similar to mine. That’s an assumption that could be false but that’s the source of my communication, and that’s the best we can do.”

All of this finally left me thinking that if what Hoffman says is right, then the answers to all our big questions are so far beyond our perception that all we can do is steal tiny glances at them, carve new edges as we evolve. And at that exact point aren’t science and art the same? The pursuit of knowledge is an edge, and language is an edge, and poetry lives at the edge of language. The poet Elizabeth Willis wrote two lines that I like to come back to: “a word is a symptom/ of what can’t be described.”

We know that quantum physics, cognitive science, and arguably all hard sciences by their nature push the boundaries of our relationship with reality. Science and art both seek to define the unknowable. Heidegger said, “[T]he poets are in the vanguard of a changed conception of being.” Wittgenstein said, “The limits of my language are the limits of my world.” These abiding truths unify disciplines in the way that language is our most innate tool. Though I’m well into this rabbit hole, I’m not afraid, but am inspired by our edges and unknowns and the many tools and points of view there are to explore them. Here at last is Borges:

So then let my glimpse of an idea remain as an emotional anecdote; let the real moment of ecstasy and the possible insinuation of eternity which that night lavished on me, remain confined to this sheet of paper, openly unresolved.