The Power of Predation in Literature

I woke to find the cougar curled at the foot of my bed.

Or, at least, I thought I did.

I accidentally bumped the sleeping cat with my foot. He rose with a gleam in his eye, arched his back in a dramatic stretch. Heat emanated from his hyper-muscular body. He began to walk the length of the bed, toward my face.

He was self-assured, as only an eighty pound killing machine can be.

I tried to yell. I could not breathe. This was the end.

“I think someone in the house had a nightmare,” one of my roommates at the Millay Colony for the Arts said the next morning at breakfast.

I did not own up to the ruckus, or the epic fight I realized I’d had with my down comforter the night before. Who was scared of a four-hundred fill goose-down-cougar? Me.

I was a resident at the Colony that November, and bloodlust was everywhere. Deer season was on, and gunshots ricocheted throughout the national forest that surrounded the Colony. The caretaker mentioned a seventy pound coyote-dog hybrid he’d seen the week before, and showed us where a bear had peeled off siding from the renovated barn, Steepletop, in which we slept.

At meal times, we had to walk the length of a football field to the main house where dinner was served. As dusk approached, I slipped on an orange mesh vest.

Do not leave the house without wearing orange, advised the caretaker.

Anticipating the dark walk back from the main house, I stuffed a high beam flashlight into my bag. After dinner, walking back to the barn in the country dark, I kept one hand on my light, the other on a pocket knife, and sang a hyperventilated cover of “Yellow Submarine” at the top of my lungs, all the time waiting to bump into a musky bear or coyote. Bristling with adrenaline, I looked over my shoulder before I closed the barn door for the night.

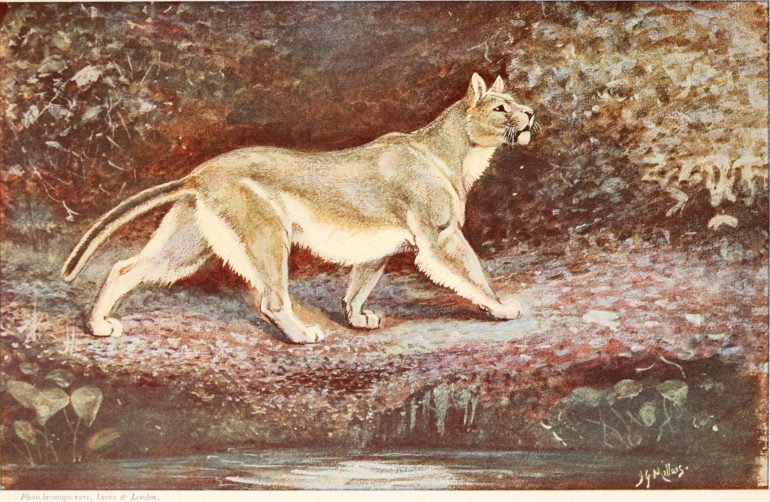

Then I read Mary Oliver’s “Mountain Lion on East Hill Road,” which says, “Once, years ago, I saw/the mountain cat. She stepped/from under a cloud/of birch trees.” Upon being seen, “flames leaped” into the cougar’s eyes, for “it was that distasteful for her to be seen.”

(Oliver was writing from Steepletop, which is on East Hill Road. But in reality, the Colony is a safe and enchanted place.)

I’m embarrassed to admit this, but that month I was electrified by my fear, the mere hint of a predator in the wings. Years later, I realize that the fear I irrationally cultivated at the Millay Colony was, at its root, connected to a primal anxiety—the anxiety of being eaten. This fear is ancient, humbling, and one we have all but removed ourselves from in the modern age.

David Quammen’s book Monster of God—The Man-Eating Predator in the Jungles of History and the Mind, discusses the way humans have ceased to tolerate proximity to predatory megafauna. He reminds us that “[g]reat and terrible flesh-eating beasts have always shared landscape with humans. They were part of the ecological matrix within which Homo sapiens evolved. They were part of the psychological context in which our sense of identity as a species arose. They were part of the spiritual systems that we invented for coping.” This fear, alongside habitat destruction, has driven humans to eradicate wolves, bears, rattlesnakes, and cougars from natural environments. Most of us no longer live with the risk of being eaten.

A fear of predators is deeply rooted in what Quammen calls the “evolutionary wisdom stored in our genes.” We, perhaps unknowingly, bring this evolutionary baggage to the page when we read. After my time at the Millay Colony, I found myself attracted to short stories that examined, or in some cases exploited, the primal fear of predators: Lydia Peelle’s “Phantom Pain,” Flannery O’Connor’s “Wildcat,” Courtney Eldridge’s “Sharks,” Ernest Hemingway’s “Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” and William Faulkner’s “The Bear.” I felt my engagement with this work was intellectual and biological.

I find the threat of predation satisfying in a short story because, when done well, it solicits a visceral reaction. The etymology of the word visceral can be traced to the Latin word viscera, which was used to refer to internal organs; the plural term, viscus, refers to “flesh.” A visceral reaction refers to an instinctual reaction, as opposed to an intellectual reaction.

Feel this at work, for example, in Flannery O’Connor’s early story “Wildcat.” A cougar is terrorizing a small village. The elderly and blind Gabriel, left behind with the women while the men go out to hunt the cougar, tries to convince himself he can fight the cat, but realizes “he hadn’t been able to wring a chicken’s neck for fo’ years. It was gonna git him. Won’t nothing to do but wait. The smell was near.”

Suddenly, Gabriel hears scratching noises by the chimney. “Lord waitin’ on me,” he whispers. “He don’t want me with my face tore open. Why don’t you go on, Wildcat, why you want me?”

In a moment of panic, Gabriel jerks himself up onto a chair and breaks the shelf he’s holding onto. And–there’s a nod to the viscera here–his “stomach flew inside him . . . and then, he heard a low gasping animal cry wail over two hills and fade past him; then snarls, tearing short, furious, through the pain wails. . . . Cow, he breathed finally. Cow. Gradually, he felt his muscles loosen . . .”

For most hominids or anthropoid apes, a direct encounter with a predator triggers a physical response—when threatened, the body enters “fight or flight” mode. Adrenaline floods the body, the heart pumps, and the body devotes itself singularly to survival. Feeling snack-sized, I walked the woods of Steepletop with tunnel vision, my ears attuned to the sound of every rustled leaf. For me, reading a well-crafted story like “Wildcat” toys with power dynamics and summons these physical memories, what Quammen says is one of our earliest forms of self-awareness–“the awareness of being meat.” It fascinates me that as citizens of an increasingly developed world we are losing this humbling awareness, that some of our essential programming may soon be rendered obsolete.

During the Scopes Monkey Trial, man’s body was called a “veritable walking museum of antiquities.” Though maybe they are going the way of the emu’s wings, the whale’s pelvis, goose bumps–our predator-related “blood memories” are a victory of natural selection and a part of a longer story–what biologist and writer E. O. Wilson calls the Evolutionary Epic, a tale of the natural world that we continue to be a part of, though some believe we are hastening our way toward a fast exit.

Wilson, when writing about the nearly universal fear of snakes in primates in his book Biophilia, notes our “sweet sense of horror, the shivery fascination with monsters and creeping forms that so delights us today even in the sterile hearts of the cities” and how this horror “could keep you alive until the next morning.” But it’s something Wilson says later in the passage that inspires me as a writer, and strikes me as the great and tragic opportunity for storytellers: “We stay alert and alive,” he writes, “in the vanished forests of the world.” As writers begin to grapple more with eco-morality, and I believe they will, they’ll need to explore these vanishing forests and species, and the ancient ways our very minds and bodies are tied to them.