The Terror of Racial Intimacies

1.

What does it mean to examine the possibilities of deep friendship—love, even—through the lens of a queer interracial reckoning with our silences? To opt for a kind of witness that exposes the violence of intimacies, a form of “domestic” violence that exists between black/brown and white people?

In 1960, when James Baldwin wrote “Notes for a Hypothetical Novel: An Address” he was working on his novel Another Country. In this and other essays, Baldwin hints at the torments that he found when trying to craft Another Country, a third-person tale that swoops in on the lives of characters, queer and straight, black and white, women and men, foreign, expatriate, and American. Another Country is a novel of collision, as Baldwin alludes, of all the myths of what it means to be American. The novel is also a collision of the silences, the ignorance, and the willful disregard of the violence that undergirds black life, queer life, and our inability to grapple with this honestly in our closest relationships, especially those that cross racial “lines.”

A determined Baldwin set out to write the story of what he called “the bottomless confusion which is both public and private, of the American republic.” In Another Country, he crafts a novel that features the terror of racial intimacies that stalk Americans in both our proximity to each other and also throughout our seemingly distant history. In order to achieve this, he chose Rufus Scott to be the central character of the story. Rufus, a black drummer from Harlem, serves as the axis upon which the fictional world of the novel revolves. When he starts a relationship with a white southern transplant to New York City, Leona, herself troubled as a woman recently out of an abusive marriage, Rufus descends, rapidly, into a brutal spiral of jealousy, rage, and shame. Existing as one half of an interracial couple in the late 1950s, he struggles with the hyper-visibility of the relationship, the blatant discrimination, and the many microaggressions they face. Stripped of their subjectivity and reduced to stereotypical public personas, Rufus is unable to comprehend his love for Leona and her love for him. So Rufus lashes out, beating Leona and drinking too much until they are both are forced to retreat from life—Leona gets taken back down south to live in asylum and Rufus throws himself off of the George Washington Bridge.

Among Rufus’s circle of white friends and former lover (in the novel, his only friends), there seems to be a tacit sense that Rufus’s suicide was inevitable. While they “hated what he did to that girl,” Rufus’s friends are mostly too preoccupied with their own lives, their own ambitions, to ponder the circumstances behind Rufus’s death. The only love Rufus has is that of his family, mainly his sister, Ida, who in the weeks leading up to her brother’s death circulates among his friends and then becomes part of their group. Rufus’s best friend is the aspiring writer Vivaldo Moore, himself something of an outsider as a poor Italian-American Brooklynite living in the Village; under the banner of grief, Vivaldo and Ida begin a romantic relationship. Like Rufus and Leona, Baldwin portrays their interracial relationship as one straight-jacketed by the external forces of white supremacy. But where Rufus was tormented by the racialized and racist ways his relationship was viewed on the public stage, Vivaldo idealizes his relationship with Ida as having the potential of dismantling racism. It’s not clear in the novel if Ida is aloof and untrusting of Vivaldo’s earnest declarations of love because he is, after all, a man who frequented Harlem as a sex tourist, or because as Rufus’s best friend she feels like he failed to help him when he needed him most.

Was Another Country a novel ahead of its time? Written and published in the nascent years of the Civil Rights movement, Baldwin, for better or for worse, according to his many critics and biographers, defied the white publishing imperative to write books solely with black main characters, living lives that white publishers and patrons at the time expected. Where white writers had long used black and Indigenous people as props in their stories, either as sidekicks or plot devices (Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mocking Bird was published to much acclaim in 1960, only two years before Another Country), Baldwin wanted to write a novel that turned away from sentimentality, as well as sociological facts that clumped people into groups and categories and charts. If we are to take “Notes for a Hypothetical Novel” as notes for the actual novel Baldwin was writing at the time, we understand that his aim as a writer was to “walk right into . . . the bottomless confusion which is both public and private of the American republic.”

2.

[L]et us say . . . that I have a friend who has just murdered his mother and put her in the closet and I know it, but we’re not going to talk about it . . . and we’re sitting around having a few drinks and trying to be buddy-buddy together, [and] very shortly, we can’t talk about anything because we can’t talk about that. No matter what I say I may inadvertently stumble on this corpse. And this incoherence which seems to afflict this country is analogous to that. — James Baldwin

Much of my friendship with B.D. was spent learning how to pass time together. Side by side, we would lay, rigid, on the mattress on his bedroom floor. We’d be on top of the brown and blue comforter, fully clothed and our faces pointed toward the only window in the room, a small square cut into the plywood panel wall. He didn’t speak much, nor did I. Mostly, we listened to music at top volume, the bleating voices of angry men saying more in song than we would ever say to each other. Listening, our silence, our comfort, was guaranteed. Because if we spoke, we’d have to talk about Baldwin’s metaphorical corpse in the closet, the incoherence at the root of our intimacy. We were not meant to know each other, much less be friends. This was in part because B.D. is white and I am black, but it is more than just the fact of race. During this period of our complicated friendship, B.D. was an avowed racist and a soon-to-be founder and leader of one of California’s “most powerful and fastest growing” white supremacist gangs, according to the California Department of Justice and the Anti-Defamation League.

I was not B.D.’s only friend of color. In fact, I met him through two mutual friends, one black and the other Chicano. The difference between them was that when I became homeless at the age of 16 and was living in a car, B.D. was the only one who offered me a place to live. At the time, as a young woman, there was no better option. I knew—at least I hoped—B.D.’s white supremacist dogma, and especially the “commandment” against race-mixing, would preclude him from expecting anything from me sexually. And yet I also knew that I wasn’t physically safe, not really. But here’s the difficult thing: I didn’t care. I was, in a matter of speaking, at the lowest possible point, unable to see any intrinsic value to my life, or my place in the world. White parental figures, teachers, social workers, and the state all tried shaping the narrative of what my blackness was supposed to mean, and none of it was beautiful, or filled with love or joy or hours of laughter. Much like the isolated and patronized Rufus in Another Country, I was filled with a kind of shame for myself, in part because I hated so intensely—both myself and the white people around me. It’s important, I think, to point to a reality that most Americans of a certain economic status fail to understand: poor rural communities are not often so sharply segregated by race as they are in the cities and suburbs. We are thrown into the same schools, the same welfare lines, the same jails, though the poor whites outnumber the poor communities of color. So, in a way, it was no accident that I arrived at the doorstep of a Neo-Nazi looking for shelter.

We lived in the part of California where passers-by averted their eyes, turning away from the poverty of the place, the shattered, forlorn adults, mean and intoxicated and overworked or out of work. We were the children of these adults, deathly bored and trapped in our bodies and limited possibilities. In that context, I’m afraid to admit, B.D. was exceptional. He was smart, funny and kind. He wore his ignorance without shame, perhaps even elegantly. He was charismatic and charming and had a great capacity for love. While B.D. nursed me out of my self-destructive trance, making sure I ate, that I kept myself safe, that I had a place to stay, he made me pay in other ways—neither cruelly nor deliberately, but simply as a matter of his own delusional “facts.” He’d leave out his racist mail order books spouting white supremacist conspiracies. He’d talk at me for hours, revising history and “citing” seemingly self-evident eugenicist truths.

It is, however, a very long walk from reality to the world of this racial fantasy, and we all watched as B.D. warred with himself. His real world was peopled by actual living and breathing black and brown folks whose humanity and complexity defied his theories. In order to be in his fantasy world, he had to deny his friendship—not only with me, but with others that he loved. He began to be heavily recruited by a large national Neo-Nazi organization, and when members of this organization drove to his house, the house I was in, B.D. calmly told me to stay inside and away from the windows. I watched from a slit in the living room curtain; seeing him standing next to them, men who looked exactly like him with their taut humorless faces, shook me out of my stupor. As a group they were nearly identical, unified in something that was more than just hate. These were the kind of men who could and eventually did commit terrible acts of violence, mostly against themselves, but also against people like me, my family, people that I love.

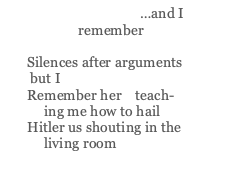

I am reminded of a poem by Shane McCrae, whose maternal grandparents, who were also white supremacists, kidnapped him from his black father and raised him to believe that he wasn’t black while simultaneously abusing him for it. In the poem, “Remembering My White Grandmother Who Loved Me and Hated Everybody Like Me,” from his collection The Gilded Auction Block (2019), McCrae captures the functional, daily aspects of racial terror in few words:

McCrae shows us how casually his white family members employ the kinds of racial violence that most of us want to believe can’t exist in our intimate relationships. This poem and others ask us to consider what it means to live with and among white people who believe or who were born to believe the lie that their humanity historically and structurally holds more “value” than that of black people.

This distorted conditioning is again taken up in McCrae’s 2020 collection, Sometimes I Never Suffered. McCrae there returns to the real-life figure Jim Limber, a mixed-race black child (who he writes about in his 2016 collection, In the Language of my Captor) who was said to have been rescued at the age of five from “his brutal negro guardian” by the Confederate First Lady Varina Davis. Jim Liber, who historians call an “orphan,” would become a symbol for Confederate apologists as an example of the compassion and anti-racism of Jefferson Davis and his family. Jefferson Davis, who among many titles was a Mississippi Slaver who owned over 100 people, is said to have “freed” Jim Limber, who lived in the family home and was a close playmate and “pet” of the Davis children. McCrae’s poem “Jim Limber on the White Embrace” reflects on the violence that is at the root of being turned into a symbol of everything and nothing, the violence that is living at the mercy of the white imagination. He imagines the moment when Jim Limber is taken from his black caregiver to live among the Davises:

What does it mean that “they” can kill you in their home? Sometimes, when it comes to intimacies that transcend racial lines, this is not a rhetorical question. Consider what it means to be killed by friends or family or neighbors simply because of race, and the ways whiteness protects. Consider what it means to be killed by your white mothers, as the 6 black and brown Hart Children were, or by your white mother and father, as Asunta Fong Yang was, or after a night out with your white friends, like Brandon McClelland was. Consider what it means to attend a party as the only black person among white acquaintances, like Tamla Horsford and Derontae Martin did, and end up dead.

Shortly after B.D. had the meeting outside his home, I left. No goodbyes, no conversation, and, most importantly, no looking back. I am not sure if my feeling of fear is a real memory or one encouraged by the kind of life B.D. lived after I was gone or if fear is the emotion that moves in when you feel like you have something to lose. It turns out for a long time, it seems, B.D. had nothing to lose. He chose to live in his racist fantasy and ended up walking the path that was expected of him. Drugs. Prison. Parole. What I know of his life I read about in reports by the Southern Poverty Law Project and the Anti-Defamation League. I saw a photo of him once online and nearly didn’t recognize him. He was so covered in prison tats, indecipherable black ink saturating every part of his body. My roommate who was looking over my shoulder mistook him to be a light-skinned black man. In a way, that seems about right.

In Another Country, as Rufus rides the A train to the George Washington Bridge where he will die by suicide, he thinks, “Many white people and many black people, chained together in time and in space, and by history, and all of them in a hurry. In a hurry to get away from each other, he thought, but we ain’t ever going to make it. We been fucked for fair.” Baldwin evokes the chaining together of black and white people, signaling slavery as the shared origin of our contact. It’s the history some Americans think we are over with, while for others, it’s the wound that has yet to be adequately addressed. Writing critically about William Faulkner, Baldwin reminds us that “Negros were not the only slaves.” If Black and Indigenous people were not the only slaves, white folks, as Rufus suggests in Another Country, are shackled as well.

3.

My friendship with B.D. was not unusual nor was it necessarily extreme. I see B.D. as an honest reflection of what it means to live in a white supremacist society, and it’s a deeply violent past. B.D. may have been a Neo-Nazi who slipped easily into simplistic and very dangerous binarist ideology, but white supremacy is made up of shades of gray. There is little difference between B.D. and the parents storming school board meetings over the perceived threat of “critical race theory,” of course, but what of the well-meaning white people who proclaim Black Lives Matter but don’t believe in prison abolition or defunding the police?

The proximity to and even love for a person of color does not foster anti-racism. This is an obvious statement and yet its opposite is at the core of a rash of popular books, such as Ibram X Kendi’s How to Be an Anti-Racist (2019), or Emmanuel Acho’s Uncomfortable Conversations with A Black Man (2020), or Frederick Joseph’s The Black Friend: On Being a Better White Person (2020), or even the sharply satirical and more critical Sure, I’ll Be Your Black Friend: Notes from the Other Side of the Fist Bump (2021) by Ben Philippe. These works have been published into milieu where there is a tacit understanding that racism is about ignorance or misunderstandings or an exercise in power in the form of self-interest. While they have their merits, they uphold the easy notion that racial justice rests in individual gestures, rather than offer up a deeper analysis that ultimately calls for a reckoning with an always violent white supremacy. All of these books, no matter how good, funny, well researched, or conversational they are, support the ideal of what Baldwin called “white innocence”—a mechanism of collective amnesia or willful ignorance of the pervasive power, historically, structurally, and materially, that white people, as white people, have and are rather unwilling, by and large, to share.

An abiding myth about racism that rests at the center of “white innocence” is that it is our separations that are the backbone to systemic racism in our laws, our economy, and our culture, and that cause us as individuals to make assumptions about people of “different” races. In this instance, as these “buddy books” show, “white innocence” is multi-hued. But neither “difficult” conversations, “hope”, a glossary of anti-racist terms, nor friendship will address the murdered bodies in the closets, or at the bottom of the oceans, or in mass graves on the grounds of boarding schools, prisons, hospitals, and missions. Neither will publishing a host of memoirs dressed up as faux self-help books that pander to a sugar-coated and frequently de-historized campaign of racial terror in America. What these how-to buddy books show is that the market demands that a black person’s story (in particular) be many things at once—instructive, evangelical, radical, and accommodating—to be considered valuable.

In, The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture (2012), Kevin Quashie attends to this beautifully:

This is the politics of representation, where black subjectivity exists for its social and political meaningfulness rather than as a marker of the human individuality of the person who is black . . .The determination to see blackness only through a social public lens, as if there were no inner life, is racist—it comes from the language of racial superiority and is a practice intended to dehumanize black people.

If black expression, as Quashie writes, has itself become a public symbol at the expense of our more private humanity, then it seems that our cross-racial intimacies risk also being mere symbols of anti-racist work.

As a novelist, Baldwin was keenly aware of the curatorial role he played in the politics of representing black life. While writing Another Country he wrestled very much with the representation of the public symbol of both his black and white characters, perhaps even the public symbol that many liberals continue to uphold when speaking of the novel—the “social and political meaningfulness” of interracial relationships as a symbolic gesture of racial progress. As novels in James Baldwin’s oeuvre go, Another Country is generally not considered his best work. It is largely read for what it says (or doesn’t say) about the possibilities of love and shared community among black and white people. Baldwin struggled with the story, traveling from New York to Paris to Israel to Turkey in search of a place to finish the book. By his own admission, the characters in the novel were elusive, and the years of working on the story, his third and his longest at the time, exhausted him, causing, for a moment, a crisis of faith as a novelist.

It is not my place to say if Another Country is a failed novel, but it is ultimately an unsatisfying work. The thing that Baldwin, I think, wanted to get to—the intensity of trouble as well as the depth of possibility for love and/or real friendship across racial lines—does not come through. Out of a cast of seven characters, only two are black (Rufus and Ida) and rarely do they appear on the same page together; when they do, there is always a white interloper. This burdens Baldwin’s black characters, reminding me of what the black writer William Melvin Kelley, a contemporary of Baldwin, once wrote: “The only time a Negro can forget he is a Negro is when he is with other Negros.” In much the same way the authors of the black buddy books take on the burden of representation for their white readers, both Ida and Rufus’s interior lives are held hostage by the white people around them. Baldwin seems to understand that he was forced to make a choice: have his black characters serve as the catalysts for greater racial awareness for the white people in their lives or have white readers continue to cloak themselves in their white innocence. It’s a sacrifice, as Ida says to Vivaldo, as he declares his love to her once again. “I’m sorry to have hurt your feelings, I’m not trying to kill you. I know you are not responsible for—for the world. And, listen: I don’t blame you for not being willing. I’m not willing, nobody’s willing. Nobody’s willing to pay their dues.”

This piece was originally published on September 15, 2021.