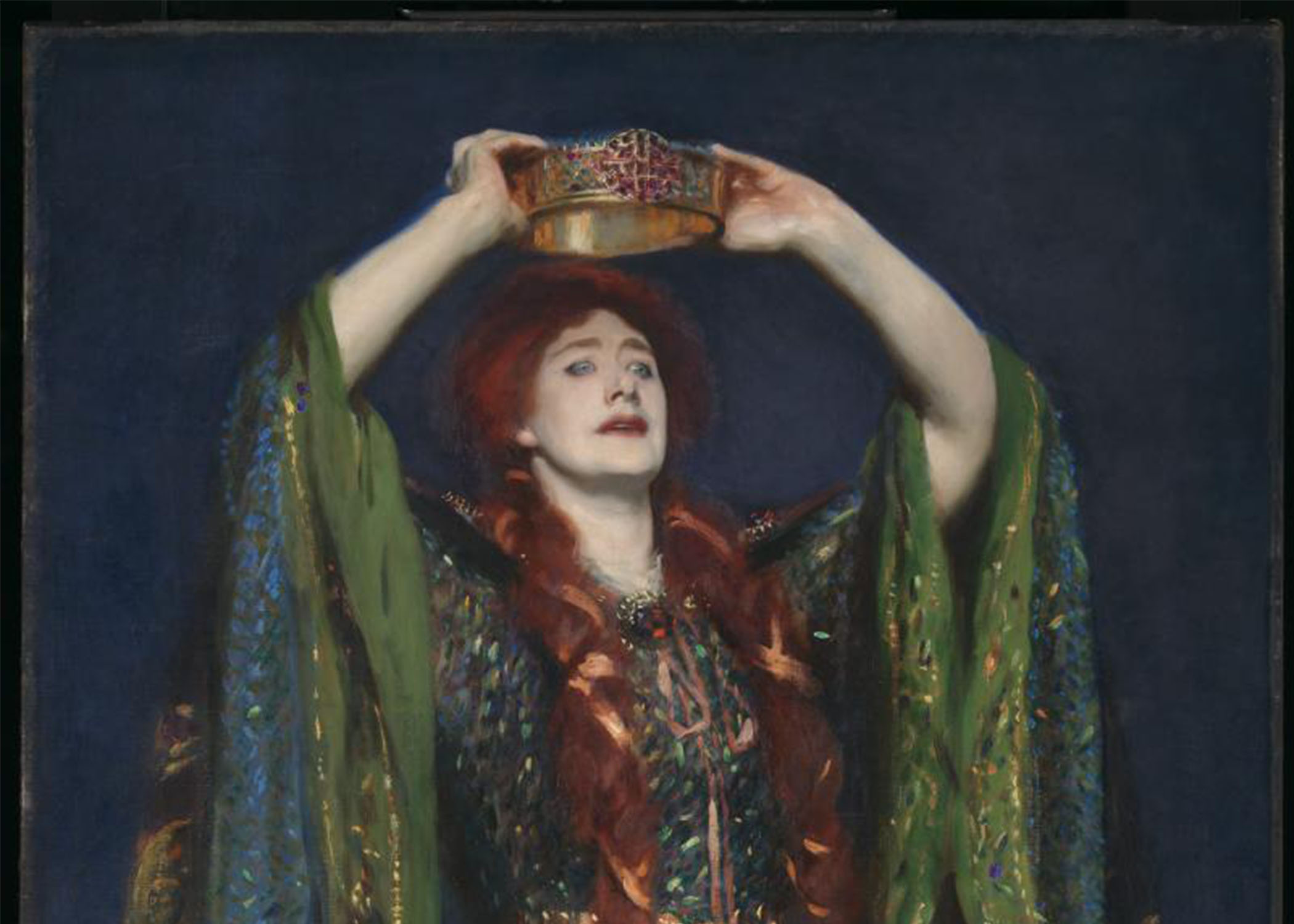

The Tragedy of Lady Macbeth

I’ve always felt a little guilty about loving Lady Macbeth. After all, who could love a woman who goads her husband into murdering their king by telling him,

I have given suck, and know

How tender ’tis to love the babe that milks me.

I would, while it was smiling in my face,

Have plucked my nipple from his boneless gums

And dashed the brains out, had I so sworn as you

Have done to this.

It’s a horrific image, layered with detail that makes the horror all the stronger. It smacks of pure evil, flying in the face of what a mother should be like, and demonstrates the lengths Lady Macbeth will go to manipulate her husband.

Still, I love Lady Macbeth for her fierceness and find her death, which comes at the end of Macbeth, tragic rather than deserved. She is unlike most—if not all—of Shakespeare’s other famous leading ladies: cross-dressing Portia in The Merchant of Venice smartly securing what she wants; star-crossed Juliet in Romeo and Juliet flouting her family’s wishes; mercurial Titania defending what is hers in A Midsummer Night’s Dream; Hamlet’s jilted Ophelia who is driven to madness. None of these women ever act as evil as Lady Macbeth, though two meet similar ends. I don’t agree with Lady Macbeth’s plan to murder King Duncan so Macbeth—and herself—can ascend to power; I am drawn by her agency, particularly in contrast to her husband’s as well as that of other women in Shakespeare’s plays.

Lady Macbeth has no trouble reading in between the lines of Macbeth’s letter that delivers news of the witches’ prophecies and Duncan’s imminent arrival. Those new to the play are often quick to attribute the drive to kill Duncan to Lady Macbeth, who quickly devises a plan, though it’s Macbeth who thinks of murder first. “[W]hy do I yield to that suggestion / Whose horrid image doth unfix my hair / And make my seated heart knock at my ribs / Against the use of nature?” Macbeth wonders immediately after learning that the witches’ first prophecy, that he will become Thane of Cawdor, has been fulfilled, making “the imperial theme” that much nearer. Macbeth calls Lady Macbeth his “dearest partner in greatness” and instructs her to “lay [the news] to thy heart.” Though the prophecy does not indicate murder is necessary to gain the throne, Lady Macbeth, just as her husband did, thinks of it, though she doubts her husband’s ability to complete the job. “Yet do I fear thy nature,” she says, “It is too full o’ th’ milk of human kindness / To catch the nearest way.” Despite the honor newly bestowed on now twice-titled Macbeth, Lady Macbeth is impatient for more power, yet no matter how badly she craves it, her gender prevents her from attaining and openly wielding it.

“Hie thee hither,” Lady Macbeth calls her to husband in her opening soliloquy, “That I may pour my spirits in thine ear / And chastise with the valor of my tongue / All that impedes thee from the golden round.” She asserts her masculine spirit uselessly trapped in her woman’s body and asks evil spirits to “unsex” her “[a]nd fill [her] from the crown to the toe top-full / Of direst cruelty.” She asks these “murd’ring ministers” to “[c]ome to [her] woman’s breasts / And take [her] milk for gall.” She asks the impossible—casting off her femaleness; rather than give in to the limitations of her gender, then, she performs them, acting as a gracious hostess when Duncan arrives, flattering him by saying what an honor it is to have him in her home. She knows just how to “[l]ook like th’ innocent flower, / but be the serpent under ’t,” as she instructs Macbeth. After he murders Duncan, Lady Macbeth fulfills her gender expectations by fainting, too delicate to take the grisly news. Though she can’t be unsexed, she plays a woman perfectly.

Part of my love for Lady Macbeth comes from this ability to perform gender to her advantage. I can imagine Lady Macbeth grabbing her husband by the arm and telling him to pull it together at several points. She frequently questions his manliness, outright asking, “Are you a man?” when he acts mad after seeing Banquo’s ghost at a banquet. When Macbeth returns with the daggers, she must return them to the crime scene, bloodying her own hands, and she tells him, “My hands are of your color, but I shame / To wear a heart so white.” Ultimately, she’s the one who secures their power, telling him to wash his hands, put on his nightgown, and pretend it never happened, though Macbeth can’t overcome guilt so quickly. Then he descends into madness—more hallucinations and murders; the illness Lady Macbeth once hoped would attend him has now consumed him. “Be innocent of the knowledge, dearest chuck,” he tells Lady Macbeth before Banquo’s murder. She once had to keep Macbeth together just long enough to murder, but now she has lost control of him.

With her husband off to England to fetch the rightful heir, Lady Macduff becomes Lady Macbeth’s foil. Lady Macduff is truly innocent, a detail that comes back to haunt Lady Macbeth in the end. Lady Macduff is motherly, serving her husband rather than manipulating him. “I have done no harm,” she says when a messenger alerts her to the imminent arrival of Macbeth’s men and inevitable slaughter. “But I remember now / I am in this earthly world,” she continues, “where to do harm / Is often laudable, to do good sometime / Accounted dangerous folly. Why then, alas, / Do I put up that womanly defense / To say I have done no harm?” Her husband has left Fife—and his family—defenseless, and she acknowledges how pointless it is for her to use “that womanly defense” that she’s innocent—it only matters what her husband has done, not her.

Lady Macduff’s observation is a direct indictment of Lady Macbeth, whose harmful actions have led to Lady Macduff’s murder, and whose “womanly defense” cannot save her. In one of the play’s most famous scenes, Lady Macbeth’s sins flood over her, tugging her into madness. Sleepwalking, with a light at her side to counteract the darkness she’d invoked earlier, Lady Macbeth tries furiously to wash her hands. “Out, damned spot, out, I say!” she weeps. The verse she initially spoke in is dropped here and replaced by prose, indicating that she’s lost her status along with her mind. “The Thane of Fife had a wife. Where is she now?” she asks. “What, will these hands ne’er be clean? No more o’ that, my lord, no more o’ that. You mar all with this starting.” She’s reliving Duncan’s murder, which marks the moment she gained power just as much as it does the moment she lost control of her husband. She also summons forth his subsequent murders, most explicitly Lady Macduff’s. While Lady Macbeth seemed to manage washing her hands of just one murder, the waters are now bloodied so much more than she intended, which forces her to acknowledge the depravity of what she’s caused. She now recognizes how much the world has been incarnadined by their bloody actions, and her ruthlessness has given way to hysteria and guilt.

In the end, Macduff calls Lady Macbeth a “fiend-like queen,” then adds in a parenthetical “(Who, as ’tis thought, by self and violent hands, / Took off her life).” My impulse is to resist Macduff’s characterization of her as fiend-like and the association with evil spirits this entails, though she asked these very spirits to fill her with cruelty at the beginning. So, of course, Macduff is right, but there’s something wrong in what he says, too. Macduff did good by saving his country but in the process lost his family, his wife who did no harm. Lady Macbeth ruthlessly harmed and cannot wash herself clean of it; she repents—albeit too late—then kills herself, but even her death does not snap Macbeth into being humane. She was once fiend-like, but she doesn’t die that way. “She should have died hereafter,” Macbeth observes, continuing, “And all our yesterdays have lighted fools / The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!” Life and death—even that of his wife—has become an abstraction, a story, a marker of the passage of time for Macbeth. The light of a candle huffed into blackness, like the blackness they’d craved.

Ultimately, I can do little to justify why my love of Lady Macbeth exceeds that of other Shakespeare women. Her power grab is despicable and her actions unforgivable. So it’s her strength that draws me, and how skillfully she works within the limitations of her gender—no matter how badly she miscalculates. I love Lady Macbeth so much because just like Lady Macduff, she fails. As women, finding safety and security is impossible, and they are both doomed in the end. They weren’t even afterthoughts in the witches’ prophecies—they were simply non-existent. To me, Lady Macbeth’s demise is tragic because she saw what it was like to be a powerless wife killed for being in the way of power and wanted to be a woman who controlled the power instead. I love Lady Macbeth, then, because the tragedy is simply that of being a woman. What more powerful way to show this tragedy than through a difficult woman to like?

This piece was originally published on March 2, 2020.