The Weather We’re Having

The weather is no longer small talk.

For months now, I have seen colleagues look knowingly across podiums and friends cinch a side eye as they say gravely: “especially in our current political climate.”

I, too, am guilty of this freighted shorthand. To think, much less say, the tangled litany of what is encysted in that climate—this weather—is a necessary and terrible labor. By comparison, the much maligned chitchat about the forecast seems a breezy catch-all.

And maybe, I got to thinking, this is because the weather has never really been all small talk.

“The weather has a privileged place in discussions of complexity,” writes literary scholar and early queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick in the posthumously published The Weather in Proust (2011).

Think of the snow in James Joyce’s “The Dead,” the last story of Dubliners (1914). As Gabriel lays paralyzed with his own sinking shame for lack of commitment to his west-born wife and to his occupied nation, he watches the snow, “silver and dark,” through the window. He imagines the flakes spreading from his hotel room on O’Connell Street—just a couple blocks away from the General Post Office that two years later would serve as the headquarters for the Irish Republic during the Easter Rising—through the bog lands of central Ireland to the west coast, which at that moment of the Irish Revival was thought to be more authentic, further removed from the metropole, decolonial. “Yes, the newspapers were right:” writes Joyce, “snow was general all over Ireland.” In the last lines, Gabriel hears the snow falling throughout the universe like a premonition, “like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”

There’s the power struggle at the opening of Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse (1927) when Mrs. Ramsay tries to rescue her beleaguered expectation of tomorrow’s “fine day” back from her (metaphysical) philosopher husband (insert my side eye here). Their love is forfeited for his correctness: it was a rotten day.

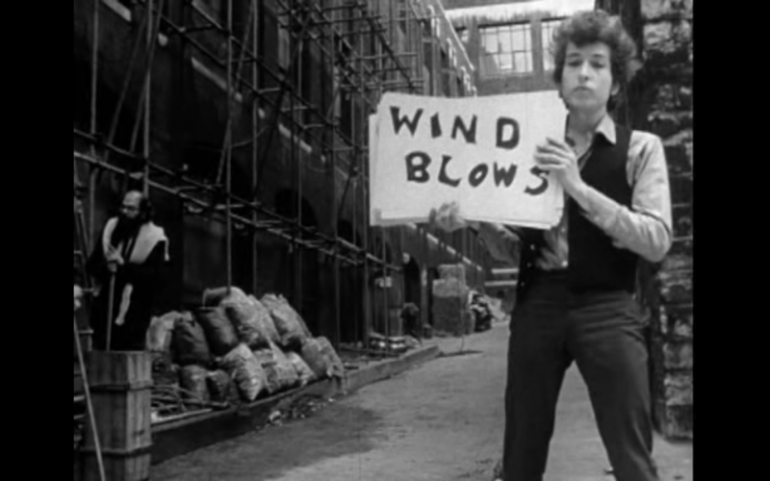

“You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows,” wrote Bob Dylan in the 1965 counterculture, anti-war anthem “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” It’s a song that music critic Andy Gill has meteorologically described as a “verbal whirlwind.” It’s also the song that inspired the self-described radical anti-imperialist, anti-racist SDS splinter group, the Weather Underground. The organization’s clandestine revolution came in the form of bombs to US government buildings—retaliatory action for attacks on the Black Panther Party, invasion in Laos, and bombing in Hanoi.

There’s the antepenultimate dissipation of Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987) which instructs us, I think, that hauntings of US (and global) slavery persist even in their disarticulations. “By and by all trace is gone, and what is forgotten is not only the footprints but the water too and what it is down there. The rest is weather. Not the breath of the disremembered and unaccounted for, but wind in the eaves, or spring ice thawing too quickly. Just weather.”

Zadie Smith, writing of her protagonist’s parents’ painful uncoupling in Swing Time (2016), writes devastatingly, “The weather in the flat changed.”

One of my friends reminded me (all the way back to middle school) that even J.R.R. Tolkien invokes the weather at the end of the fantastical The Lord of the Rings trilogy (1955). After the cleanup, the menace of Sauron’s future return lurks. “It is not our part to master all the tides of the world, but to do what is in us for the succour of those years wherein we are set, uprooting the evil in the fields that we know, so that those who live after may have clean earth to till,” Gandalf reassures his compatriots. “What weather they shall have is not ours to rule.”

And those are the subtle asides. The calamity of weather disaster in literature offers more overt indications of those who are vulnerable and exposed. From Shakespeare’s encroaching storms to Richard Wright’s floods, from Zora Neale Hurston’s hurricane to Haruki Murakami’s quakes (or maybe better said: aftershocks), we learn that we have to keep our eyes on the skies and our boots on the ground.

As Sedgwick works through Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (1913), she conscripts weather into her object’s quixotic mysticism. On the one hand, weather has a measurable “rule-bound cyclical economy” and, on the other, the “irreducibly unpredictable contingency of the actual weather.” As Proust’s protagonist, described as an “animated barometer” who suffers from “attacks of breathlessness,” unravels in the ginormous tome (4215 pages), Sedgwick’s careful reading convinces us that the narrative power and political stakes are in the weather. It is the atmospheric plodding “daily ground-tone pulsation” of the weather alongside its capricious “gem-like preciousness” that define the novel’s parameters and possibility. The weather is both expected and unknowable.

It is also the weather, writes Christina Sharpe, in her latest book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016) in the palpably present-past of the Middle Passage that holds the antiblack climate in which black lives are lived precariously close to death. Following Beloved, Sharpe’s “only certainty is the weather,” the “pervasive climate,” the “willful disasters.” In symmetry and stark relief to Proust’s bourgeois breathless asthmatic, the weather causes the atmospheric unsurvivability for black persons—for revolutionary philosopher Frantz Fanon (“We revolt simply because, for a variety of reasons, we can no longer breathe.”) and for forty-three-year-old Eric Garner who was murdered in 2014 by New York City Police (“I can’t breathe.”). These “attacks of breathlessness,” the assaults of aspiration, are what’s at stake in our weather. And still, Sharpe insists on possibility within that foregone conclusion. “The weather necessitates changeability and improvisation; it is the atmospheric condition of time and place.” “Here,” in the weather, she writes, “there is disaster and possibility.”

Some weather we’re having.