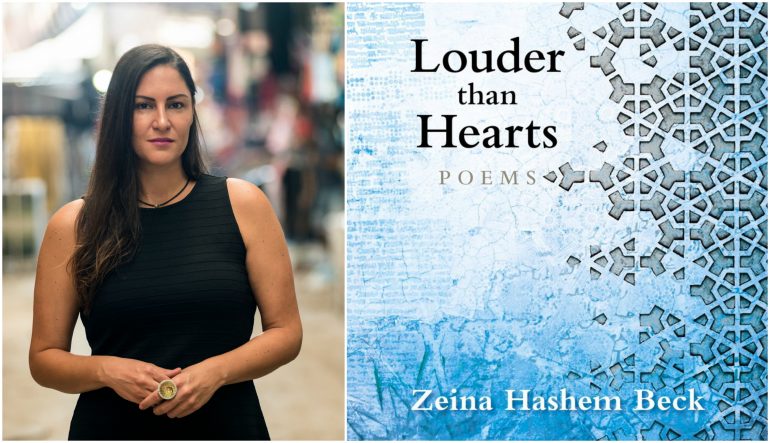

“The Woman in Me is Thousands of Years Old:” An Interview with Zeina Hashem Beck

Zeina Hashem Beck, former Ploughshares contributor, is a master of juxtaposition. Her poetry ranges thematically from the trauma of war to love songs and reminiscences of a childhood in Lebanon. The language is multi-layered, interspersed with Arabic words and cultural references, and resonant with a musicality that builds and twists, line by line. I witnessed the effect of Hashem Beck’s juxtapositions at a recent poetry reading in Dubai—one moment I was laughing along with the audience, and with the next turn of phrase she delivered us into stunned silence and even some tears.

Hashem Beck’s voice achieves new power in her second full-length poetry collection, Louder than Hearts, which debuted in April of this year. “Her poems feel like whole worlds,” Naomi Shihab Nye writes in one of the book’s blurbs, and indeed these poems transport readers to living rooms and streets and cities that feel both emotionally familiar and newly imagined. While her previous work (her first full-length collection, To Live in Autumn, and two chapbooks, There Was and How Much There Was and 3arabi Song) established Hashem Beck as a passionate, edgy, and linguistically skilled voice, this new book delves deeper into the personal and rings with greater urgency.

I spoke with Hashem Beck about her new book, the themes of fragmented languages and land (and the beauty that exists amidst the brokenness), the notions of inheritance and legacy, the mutability of memory, and the tragic events in her life that eventually generated a writing surge. She also shared her thoughts on her creative inspiration, her love of the spoken word, and where her poetry might take her next.

Laura Haugen: The dedication in your new collection, Louder than Hearts, reads: “to our broken languages & our broken cities.” Can you talk about what you mean by this sense of brokenness?

Zeina Hashem Beck: Yes, in terms of “broken languages,” I guess it’s about existing at the intersection of Arabic, English, and French. It’s also about writing in the colonizer’s language and “breaking” it, using it your own way. I speak all the languages I know in a broken manner. And I’ve always felt guilt toward Arabic—it’s my mother tongue and I don’t write in it because I’m afraid of messing it up grammatically if I do (the formal Arabic, that is). I feel more comfortable writing in English. Writing this book, I began to question what it means to live simultaneously inside these broken languages. I also find myself asking, “What is a mother tongue? Has English become a sort of mother tongue too?”

“Broken cities” refers to the wars around us in the Arab world, and the trauma and displacement that come from that. I grew up in Lebanon, so in a way, I’ve always been surrounded by/aware of war, whether in my country or next door. But it wasn’t a constant “oh my god, we live in a war-torn country” kind of thing. When the Lebanese civil war emerges in my poetry, it’s always the little things, like the water and the electricity [shortages], the stress that I felt my parents were going through but I didn’t really understand. And sometimes I don’t remember these things exactly as they were, so there are broken memories as well. All I remember from the time we fled to Cyprus when I was a child, for example, is a whale in the sea, which my parents tell me I made up.

What I wanted to do was to take this idea of brokenness, and yes, acknowledge the hurt, but also celebrate it. I wanted an empowering angle that says, “Okay, there is daily beauty and we can resist and we can survive.”

LH: I sense in your poetry a wholeness, though, and a richness of words, in how you are able to draw on different languages and cultures to add new layers of understanding and context. I read in an interview you did once that your mother told you to read the French-Arabic dictionary as a child. Do you think that from a young age you were able to bridge these different worlds, and was that the start of your fascination with words?

ZHB: I don’t know—it’s just how I was, or who we were, simultaneously living in three different languages, though I wasn’t aware that there was anything special or interesting about that until later, looking at it from the outside. I spoke Arabic with my parents, French with my teachers, and I began to learn English when I was twelve. I think that memory of delving in and out of a bilingual dictionary relates both to the idea of translation and definitions. I think poetry as an art is, in part, about constantly redefining. It’s also about translation: in my case, how do I literally translate from one language to another, but also, more generally, how do I translate this idea/feeling into words?

LH: There are some common themes, I believe, in all of your poetry books, but in this collection, I am struck with the feeling that these poems are more urgent and personal, delving deeper into your life. Do you agree?

ZHB: I’m so happy you felt that. I do feel that. One thing I kept saying to myself while writing the book was that I would only include poems–and only write poems–that felt absolutely necessary for me at the time. I constantly asked myself this question–“What is necessary to you right now, Zeina?” And so, I’m glad you feel the urgency, because the book was written in an intense period of dealing with all this–and [the poems] do feel urgent to me, and they do break my heart.

LH: It seems that you were struggling through some personal grief too after the death of your cousin in your hometown of Tripoli.

ZHB: What happened was, it was August 2013, and my cousin was shot on the street outside his house in Tripoli [Lebanon]. I think you are in constant disbelief, you know? He was just standing there eating, waiting for the electricity to come back on so he could take the elevator back up at midnight, and someone shot him, and two other men died as well. His death probably triggered my whole questioning of motherland and motherhood. I thought, “What is my relationship to this city who is my mother and has somehow taken away my cousin?” It’s possible the entire collection started from that, though it ultimately expanded and went beyond that.

LH: Was the first poem you wrote for this collection “Dismantling Grief”?

ZHB: The very first poem I wrote in response to my cousin’s death was “After the Explosions”–it was a few months later. The poem doesn’t directly deal with his death, like “Dismantling Grief” for example, but it was the first that alluded to it. The explosions in that poem happened in Tripoli two days after my cousin was shot. I remember my friend saying to me, “You will write about this.” I was crying, and I said, “I will never write about this. I cannot write about this.” And then a few months later, I was writing this poem and realized: I AM writing about this.

LH: I find that the women in your poetry are strong, dynamic, and complex characters–that despite the pain and difficulties they face, they are not portrayed as helpless. I see strength in the way your mom, your aunts, and other women are portrayed, and sometimes even humor despite the tragedies around them. Was there an intentional focus on these strong, complex women as you wrote this collection?

ZHB: With this collection, Louder than Hearts, in particular, I wasn’t aware of this focus. And by definition, poetry complicates, it leaves you questioning, doesn’t it? It doesn’t give you a flat portrait of anyone, so I’d like that to happen with any poem of mine. But later on, after the collection was almost done, I did notice that there were all these strong women in there. And this was more of a conscious focus in [one of my previous chapbooks] There Was and How Much There Was. In Louder than Hearts, I wasn’t initially aware I was writing about women, too. For me, it was about memories. It was about language and land. But the idea of a motherland and a mother tongue is connected to the idea of “mother” and “motherhood,” so of course that’s going to be there in the poems too, when I write about my mom and my aunts and my memories of Tripoli.

The title of the collection itself is taken from the poem, “Louder Than Hearts and Derbakkehs,” and that poem sort of takes a look at all the women inside me—my mother and her mother and her mother and so on. It’s a matter of asking, “What did I inherit, and what am I passing on to my children, as an Arab mother?” And how we see our mothers and how our children will see us. So I’m wondering about all of that, and that’s why the poem begins with, “the woman inside me is thousands / of years old.”

LH: There is a sense of musicality throughout your poetry. How does a poem come to you–is it primarily by ear, through the music or rhythm of words?

ZHB: I can’t really pin down where a poem comes from. Sometimes it’s from a conversation, an image, a sound, a memory—the possibilities are endless, as long as you’re listening/waiting/doing the work. But yes, music and rhythm are essential to all poetry. If I encounter a poem and I love it, for example, my first instinct will be to get up, walk around, read it out loud, and just sort of fill the room and the air with the sounds of that poem. And the way I write poems is like that too–a line will come and I’ll start writing and pause and go back up to the first line to read it out loud.

The very first poem in English that really shook me as a university student was “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by T.S. Eliot. I remember reading it in a thick anthology in my living room, and I remember very clearly my reaction to Prufrock was, “I don’t get it, but I feel it’s beautiful, and I’m just going to read it out loud now to see if I can get into it.”

LH: What comes next for you, now that Louder than Hearts is out in the world?

ZHB: All poets have obsessions, and some of mine have been language, memory, place, home, and belonging/not belonging. I think I will always explore these, but I also want to try something different. There’s more I’d like to explore about love, womanhood, and motherhood, and even the way I feel we women writers (I’m generalizing here, I know, but still) might question ourselves when we write about these topics—there’s still stigma there, that this might be less “serious” or less “important.” That the motherhood poem is too sentimental or clichéd. But for now, despite the hunger and restlessness that comes with being a poet, I feel I should just breathe, let ideas happen, and allow myself not “knowing.”

Image: (l) Natheer Halawani