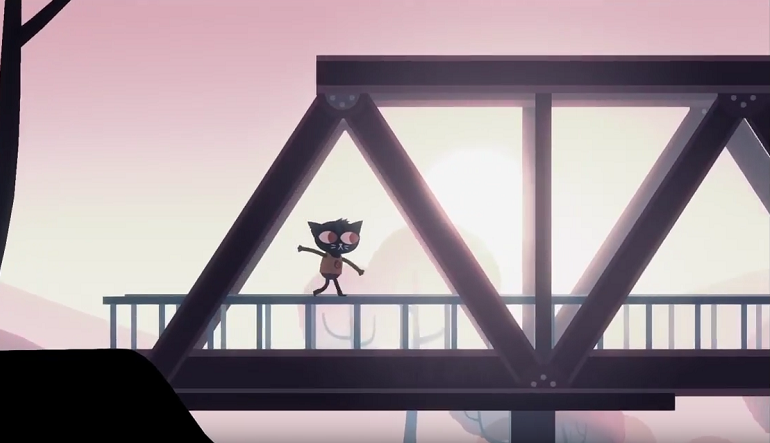

Unhaunting the Small Town Narrative in NIGHT IN THE WOODS

When I was a young kid growing up in northern Vermont, there was this rock in front of my parents’ house that I’d sit on to see across the road and down this slope of trees across empty fields that outstretched to the borders of a lake. I used to stare at all this and think that in a decade, maybe less, all the trees, all that green, would be wiped away. I dreamed about it all being smoothed down with concrete, or built over with houses until our rural road became a suburb. I wanted neighbors, I wanted civilization, but maybe more than that, I wanted to be anywhere except there. The first moment I could be, I was.

Everyone has their own leaving home story, but for country kids desperate to break out of their hometown, that story is formulaic. You talk to enough of them and you find the common elements—feelings of enclosing walls, seeing the same faces, the same spaces repeated until they become like a prison. You hear these stories and you can get the impression that all small towns are maybe the same small town, amounting to slight riffs on the same chord progression of geography.

It felt natural, then, that in the game Night in the Woods, when the main character Mae Borowski plays with her freshly reformed, unnamed band of twenty-year-olds, their first song includes a chorus that’s more like a plea: I just wanna die anywhere else. If only I could die anywhere else.

The lyrics are goofy, but undeniably earnest, and that descriptor does better to cover Night in the Woods than anything else could—it’s a game about going home to a dying small town.

I didn’t have to think about these spaces for a long time until the election. That image of decaying American rural towns was thrust back into the consciousness as a political campaign pinned its victory to them and a stream of investigative pieces tried to understand them. What they presented was almost monolithic—this depiction of simple and ignorant people being crushed underneath the weight of something they didn’t understand. The landscape was familiar (you’d be surprised how much a neighborhood of double-wide trailers in Louisiana looks like one in rural Texas or the Northeast) but the voices of these people were all off. The depiction was a half-truth.

When Mae goes back to her hometown of Possum Springs, she’s a college dropout. Twenty years old and overwhelmed by isolation and mental illness, she goes back to the one place where the ground felt steady. Her friends are a gay couple and a goth girl who runs a hardware store because her dad can’t. They’re in a band together where Mae plays the bass. Also, Mae is a cat.

Possum Springs spreads out like a bright and colorful children’s book version of a small town where the residents are anthropomorphic cats, birds, and alligators. Night in the Woods leans into this Scott McCloud idea of cartoon universality—the more details you strip out, the less specific you make it, the easier these faces can be our faces and these towns our towns.

The first moment Mae gets back home, she’s alone at a bus stop. She looks for her parents, then calls them on a payphone, only to learn that they’d forgot. They thought she was coming in tomorrow. This is a quiet scene that reminds us that things rarely work out how we expect, but for me, this was a moment of shock.

For me, I was back to being twenty years old, a college sophomore just home for winter holiday break, and I was waiting in the only major airport in the state. I was looking through strange faces and wandering back and forth, desperate for a cell signal. There’s a pit your stomach that opens up every time your parents let you down, and here I was in Night of the Woods, weaving through these same conversations again like a dissociative sleepwalk through memory. For now, this town was my town, and these people were the small-town people I knew.

When Mae moves back to her hometown, she starts having bad dreams. Hazy, neon dreams under constellations where dead gods come alive as omens—they float in as a reminder that beneath every pretty and tidy picture is something hidden and more complicated. All the stores you remember are closing. That unmoving and solid idea of your parents gives way to two people with a failing mortgage, forced into service industry jobs. Your friends, your perfect and great friends, are people recovering from abuse and lost childhoods.

That children’s book image of the American small town is not the small town. It’s the cartoon veneer hiding a heavy weight of reality and problems. That presentation is an outdated one that pushes the marginalized people of these places out of the picture. In the game, this culminates in the last act, which reveals a secret death cult sacrificing lost causes to a pit in an abandoned mine. On the surface, this is a blunt reflection about how the older people of these communities try their best to snuff out change and reinforce the status quo that they remember. They kill people who don’t fit their outline to maintain a town that appeals to their nostalgia, not the one Mae remembers and not the one her friends live in.

When Mae is brought face to face with this potential version of Possum Springs, a static town built on the thrown-away lives of the disenfranchised, she says no. “When my friends leave. When I have to let go. When this entire town is wiped off the map. I want it to hurt. Bad. I want to get beaten up. I want to hold on until I’m thrown off.”

The small-town community is only worthwhile to maintain for as long as that term community is genuine.

The fiction about small-town America—games like Night in the Woods or novels like John Darnielle’s Universal Harvester—come at a time where they’re unintentionally poised to politically rehabilitate the understanding of these places.

“Not everybody wants to get out and see the world. Nothing wrong with that,” the narrator of Universal Harvester confides. “Sometimes you just want to figure out how to fit yourself in the world you already know.” When depicting these spaces, it’s been easy to slip into this idea that the dying town is a coffin built for a certain type of people, but to fall into that trap is to ignore the people hiding in the waysides of political interviews—the outcasts, the poor kids, and the disenfranchised—for whom the small-town still provides an equally emotionally viable space to explore.

In Universal Harvester, there are still things buried underneath the surface of small-town Iowan life. There’s no death cult, but there are tapes. Blurry footage spliced into VHS tapes of She’s All That depicting people in hoods and women tied to chairs. The footage disturbs anyone who watches it but, if they discern the right locations and trace them back to their sources, what’s there is not a mystery or a murder, but an answer: that there’s only so much grief we can keep hidden before it finds its way to the surface.

What’s hidden in Universal Harvester’s small town is ultimately a cult of bared emotional experience. People are forced into chairs not under threat, but to experience feelings they couldn’t find otherwise, and they enshrine that moment in cinematic amber. Underneath the weight of an expected emotional culture of small-town life, people bend to keep steady.

Communities naturally change. They shift with the loss of job markets and demographics until, ultimately, what’s dying isn’t the American town, but the specific idea only certain people held of it. The dying American town, then, is maybe already dead and exists as a ghost haunting over a people who wouldn’t know that questioning it is an alternative. Now, though, maybe more than in recent memory, these things remind us not to reject, but interrogate that handling of these spaces—that as Mae’s grandfather once asked—to unhaunt a haunted house.