Woolf at the Table: Good Dinner, Good Talk

I have always been enchanted by Virginia Woolf and—being an avid cook and food writer myself—by gastronomic references in literature, both fiction and nonfiction. So when I learned about a book about the eating habits of the Bloomsbury set, of which Woolf was a member, I took notice. The Bloomsbury Cookbook: Recipes for Life, Love, and Art is a compendium of recipes, food-related paintings, and biographical anecdotes that sheds new light on the members of that coterie of British artists, writers, and thinkers. The book sparked in me a new interest in Woolf’s novels. In this book and in Woolf’s work, she comes across as a food lover. Yet, like her novels, Woolf’s relationship to food is nuanced and complex.

I have always been enchanted by Virginia Woolf and—being an avid cook and food writer myself—by gastronomic references in literature, both fiction and nonfiction. So when I learned about a book about the eating habits of the Bloomsbury set, of which Woolf was a member, I took notice. The Bloomsbury Cookbook: Recipes for Life, Love, and Art is a compendium of recipes, food-related paintings, and biographical anecdotes that sheds new light on the members of that coterie of British artists, writers, and thinkers. The book sparked in me a new interest in Woolf’s novels. In this book and in Woolf’s work, she comes across as a food lover. Yet, like her novels, Woolf’s relationship to food is nuanced and complex.

Food, in Woolf’s hands, rises to a level above physical meaning—it becomes more than a delicious meal. In her early writings, it seems that meals were little more than an excuse for intellectual people to gather. Woolf was curious about food and understood its importance, yet she felt that in her time, too much attention to such seemingly mundane topics would be looked down upon.

Torn between what she knew to be significant and what she knew to be literary propriety, she deplored this restraint in her celebrated essay, A Room of One’s Own:

“It is part of the novelist’s convention not to mention soup and salmon and ducklings, as if soup and salmon and ducklings were of no importance.”

In this essay, she famously says, “A good dinner is of great importance to good talk. One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well.”

In Woolf’s novels, food is more than an epicurean pleasure. According to The Bloomsbury Cookbook,

“In her novels, Virginia Woolf often employed ‘the dinner party’ situation to bring her characters together and to expose social inequalities; food can be used to influence and to manipulate. In To the Lighthouse, for example, William Bankes is seduced by ‘Mildred’s masterpiece, boeuf en daube: “It was rich; it was tender. It was perfectly cooked.”

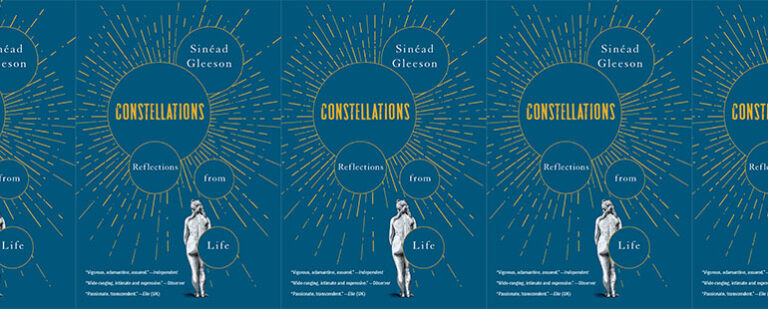

Indeed, To the Lighthouse references food as one would sprinkle sea salt on gourmet fare. Soup is mentioned on at least 10 pages in the Vintage Classics edition I possess and read when I crave the charm of her prose as much as the food she describes. We also see a deviation from the usual restraint of her contemporaries when Woolf serves up two pages of a delightful description of boeuf en daube (née French beef stew), contrasting its flavor with the “abomination” that “passes for cookery in England.”

” … an exquisite scent of olives and oil and juice rose from the great brown dish as Marthe, with a little flourish, took the cover off. The cook had spent three days over that dish. And she must take great care, Mrs Ramsay thought, diving into the soft mass, to choose a specially tender piece for William Bankes. And she peered into the dish, with its shiny walls and its confusion of savoury brown and yellow meats and its bay leaves and its wine … “

Woolf shows a keen interest in cooking, as seen from the salmon in Mrs. Dalloway to the boeuf en daube in To the Lighthouse. She was a baker of bread, according to Jans Ondaatje Rolls, the author of The Bloomsbury Cookbook.

You would think that someone who cooked and so reveled in portrayal of food would be a lover of food. However, Woolf’s numerous biographers and great niece, Emma Woolf, have suggested that Virginia Woolf suffered from anorexia nervosa.

In her biography of Virginia Woolf, Hermione Lee writes about Woolf’s “reluctance to eat and severe weight loss.” The cause was apparently was anxiety or emotional turmoil, not the desire to be thin. When life got too much, it seems, she stopped eating. As Lee notes, “Anorexia arises from an obsession with one’s body. That does not seem to be the case here. She simply could not eat.”

As a fan of Woolf and gastronome, I wonder why on earth Woolf would not eat well. Perhaps, she hated British food? Rolls writes in her book on the Bloomsbury group that Woolf was charmed by the food of France and Italy when she visited those countries.

“English food was unadventurous, bland and overcooked, but to eat foreign foods and wines was to be enraptured by a symphony of flavors and desires.”

The Bloomsbury set is mythical. They were talented people who were ahead of their time. But there is also a certain aura of gloom that has hung over the group, thanks in part to some early deaths (two by suicide) and the way they have been represented in books and movies. By focusing on food, though, The Bloomsbury Cookbook shows them in a new light.

“There’s a lot of evidence that she was in fact funny, good fun and joyous,” says Rolls about Woolf. “She saw life in Technicolor. She captured the moment and enhanced it, and she was very perceptive and absorbed so much. She had her dips, but she was 90% positive.”

How could Woolf think well, then, or love well, or even sleep well, if she didn’t indeed dine well?