(Writing) Exercise: Self-compassion

I’m talking here of memory’s difficulty. Difficult not in the way I have to wrack my weak brain to remember what happened, but in the way I’m forced to face that time I let my brother, bleeding from the mouth, run the mile home alone. Difficult in the way that looking back prompts me to see myself, as James Agee puts it, “disguised as a child.”

And what an ugly costume it could be. Holding my youth at arm’s length makes clear how royally fallible I really was. I see my foibles for the first time. My limitedness had hid them from me—a kind of Dunning-Kruger effect. And this is difficult.

As in looking back on the stack of birthday cards from my grandmother I tossed out, thinking my desk had no room. Into the wastebasket that lets every memory in and none out. I didn’t know what should be kept and what chucked. I didn’t know I was in the room with my grandmother herself, who had touched the card at its edges, wheezing over the short note with her reading glasses on. And I didn’t know that the thrown-away card would become sad and inimitable when she dies.

My grandmother tried to warn me. She dated the card at the top right corner so that I too would know posterity as always looming. Of course I see this looking back. She dated it to please the grandfather she knew I’d become, on whose lap she sat with a little girl’s wide eyes, nearing the end, nearing the beginning.

That I was so wrong when my rightness seemed so incontrovertible ensures that it will happen again and, when I least expect it, again. It’s probably happening as I speak. I suspect that I am defenseless against being wrong without knowing it. If this suspicion is true, then let a bit of vulnerability come from it, forced not down but up out of myself, the steady reverse-drip of which can help me become both more upright and a better writer.

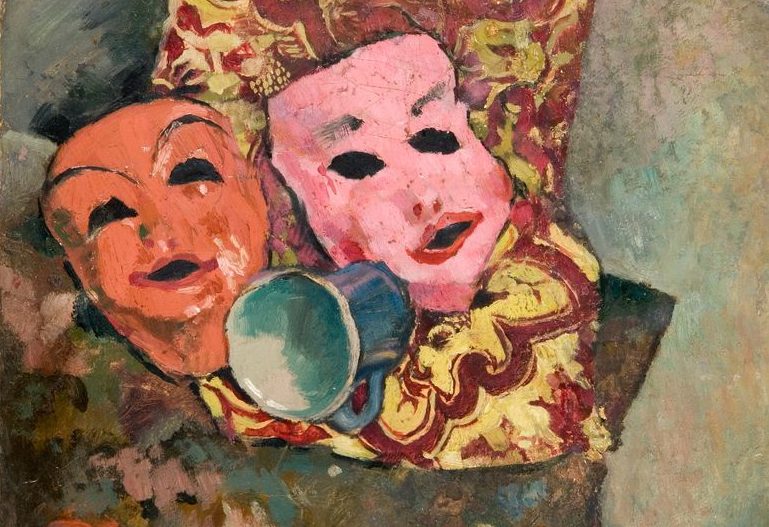

My grandmother would forgive me, but I’m harder on myself. I want to turn away. Here I try to think of the writers who look unblinkingly at their own pasts: not to remove their masks, or to curse them, but to understand why they were worn. Who does this better than James Baldwin? In Notes of a Native Son, he watches children being led up to his father’s open casket. “Their legs, somehow, seem exposed, so that it is at once incredible and terribly clear that their legs are all they have to hold them up.” These could be his own thin legs he’s remembering. His own fear. All of ours.

And later in the essay when he writes, “One of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, that they will be forced to deal with pain,” I feel he’s urging me to look my former snarly selves, blind to their own ways, right in the eye. They need to be told better, yes, but then kissed on the forehead—if they’re willing to receive it – by me now. This may be the most vital part of remembering. They weren’t infinite. They really didn’t think there was room in the desk. They only knew what they knew and not what I would later know. The kinder I am to them, the kinder I’ll be to my future selves, I’ll put money on it. Such kindness, though, is difficult.

Writing this, I can recall the time in fourth grade when I hated my kindergarten self for not knowing how to tie my shoes. I pity now both the poor kindergartener who didn’t know how to tie his shoes as well as the poor fourth grader who didn’t know a thing about self-compassion.

And I, at this moment, deserve forgiveness from the man I’ll soon become, though I don’t yet know why.