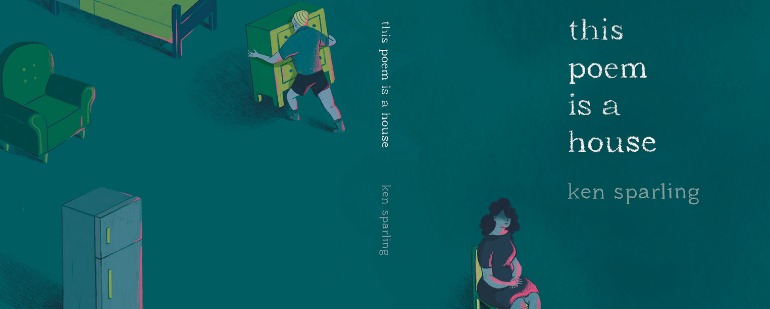

An Interview With Ken Sparling

Toronto’s Ken Sparling is the author of six novels, including Dad Says He Saw You at the Mall (Knopf, 1996; mud luscious press, 2012), Hush Up and Listen Stinky Poo Butt (self-published, 2000; Artistically Declined Press, 2010), [untitled] (Pedlar Press, 2003), For Those Whom God Has Blessed With Fingers (Pedlar Press, 2005), Book (Pedlar Press, 2010)—a book that was shortlisted for the Trillium Award—and Intention Implication Wind (Pedlar Press, 2011), but he has somehow fallen below the larger radar. His work has long held a kind of cult following in both Canada and the United States; fans on either side of the border know him as the “writer’s writer.”

In Maisonneuve magazine, Pasha Malla once wrote that “Ken Sparling is the one of the funniest, most heartfelt, uncompromising, perceptive and mind-altering writers in Canada. He will change the way you think, read, write (if you do such a thing) and see the world.”

Sparling’s recent novel is This Poem Is a House, newly published by Coach House Books, and edited for the press by Toronto writer Derek McCormack.

Q: I’m curious as to how you got to this point—you’ve mentioned Gordon Lish’s editorial assistance for Dad Says He Saw You at the Mall, for example—but what and who else have influenced the ways in which you approach the novel? And, so far at least, the novel is very much the form in which you work: was it simply Lish’s influence that directed you to the novel, or were there other factors in play as well?

A: I like the way Jonathan Goldstein interprets “novel” in his blurb on the back of This Poem is a House. He says that a novel should be novel: as in “of a new kind or nature; strange; previously unknown.” That’s from the Canadian Oxford Dictionary. Isn’t that great? I love that dictionary. I love to think of my work as strange and previously unknown in nature.

But when I’m actually writing, I don’t really think of what I’m doing in terms of a genre. I just write. It becomes whatever it is called when someone else (usually the publisher) decides to call it something. I’d probably just call it a book, and it only becomes a book at the point in the writing process where I feel like I’ve amassed enough material to make a book. Or I reach a tipping point where I want to share what I’ve been writing and I need a vehicle for that. Up till then, I just write. I might have these fleeting moments where I wonder what I might wind up doing with something I’m in the midst of writing, but I don’t get serious about making something that might be qualified as a book—or novel, or novel in verse—till I’ve got a large majority of the material created already. And even then, I just think in terms of pulling it together into a single entity—I don’t label it as anything, really.

I feel like my work doesn’t function as a novel in the traditional sense, so I’ve always been uncomfortable with the decision to call my books novels. And when I say uncomfortable, I don’t mean to suggest that I’m sorry my books have been called novels. I really love that they’re called novels. When I say it makes me “uncomfortable,” I mean in the sense that I keep wondering what that even means. And I want to keep wondering what that means, what everything means—I want to be surprised—and calling these books that don’t function as novels “novels” seems like a wondrously surprising thing to me.

My greatest influences are those moments in my past where I’ve been surprised, or where I’ve surprised someone. Those are the moments that stay with me. Reading Jonathan Goldstein’s book Lenny Bruce is Dead was one of those instances where I was profoundly surprised. I remember reading that book, thinking, shit, Goldstein is in trouble here, he’s not going to be able to pull it off. But I’d get to the end of a section to find that he had pulled it off, gloriously. And he did that repeatedly, almost without fail, throughout the entire book. It was a sort of harrowing experience, reading that book, partly because I loved Goldstein and I wanted him to succeed. And it was all the more exciting and profound for having been harrowing.

My grade eight teacher, Mrs. Foxwell, was a great influence, this time because of something I did to surprise her. We did a unit in English where you had to write three pieces that had spring as a theme. I wrote this piece that pivoted on using repetition in a really hoaky way, then turning the thing on its head at the end. Mrs. Foxwell marked every one of my repetitions with a red pen, commenting that I should find other ways of saying what I was saying, in order to introduce some variety into the piece. Then, at the end, she saw what I was doing, and she wrote a note that said to ignore all her markings and leave the piece exactly as it was. This still stands out for me more than forty years later because I knew that I’d managed to surprise her. She had me read that piece to the entire class (I was mortified) and then she put it in the year book at the end of the year. I loved that woman.

And something similar happened with Lish. Once, and only once, he marked up the beginning of a story I’d sent to The Quarterly and then wrote a note retracting the markings. My impression in working with Lish was that he went through a piece once, marked it as he went, then moved on to the next piece. So when he had to go back and revisit what he’d done on the first pass in this piece I’d sent, I felt like I’d really accomplished something.

Q: Part of what I’ve always appreciated about your work is your approach to subject—writing out what others might consider the mundane aspects of simply living day-to-day—elements that you make seem almost magical and surreal. What is it about the small details of the everyday that appeals?

A: I like those moments when something ordinary transforms you, or transforms the world and for a moment your perspective changes. It’s precisely because it’s something you might not normally pay attention to that it strikes you as so profound. Like the wind turns your hair into something it’s never been before, or the light coming through a window transforms a face you’ve lived with for forty years but never seen in this light. Or like when you’re spreading peanut butter on toast the way you have a thousand times before, but suddenly you find you haven’t got the will to move the knife. Or you’re lying in bed like you have every morning of your life and you suddenly pay attention to the little bumps where they’ve stuccoed the ceiling. It seems to me that there’s something profound and deeply moving—often painfully so—behind every simple, ordinary moment we live in this world, right up to the moment we die. When you notice these moments, you feel like you’re in the presence of something big and beautiful and painful and heartbreaking—and maybe you’re just sitting on the couch in your living room looking at the tree behind your house, or standing at the bus stop at five o’clock in the morning and all you can hear are some birds and maybe the tires of a lone car on a road far off somewhere. I’m not even sure where it comes from, but I’m always happy when I’ve been writing and I look down and it’s there, that simple mundane stuff—like you say, there’s a kind of magic to it. There’s so much peace in those moments. The narrative grows quiet, slows down, evaporates, and you see what’s really there. It isn’t so much that I’m enchanted by the simple dailiness of ordinary life (I am); it’s more like I’m looking for a way to quiet the busyness that overruns the silence, a silence that is already always there beneath that noisy narrative, waiting for me to notice it.