It Might Be Lonelier Without the Loneliness: Poetry and Loneliness

Over my desk I’ve mounted two postcards, curated toward conversation:

It might be lonelier

Without the Loneliness

—Emily DickinsonMy vagabondage

is unlonelied by poems

—Fanny Howe

Some days, these lines seem like a call and response. Other days, they are in conversation with one another. Still, others, they seem to argue with themselves. Dickinson offers Loneliness as a companion against its own effect, a paradox, certainly—the balm growing beside the nettle. Howe, on the other hand, offers poems as the companion on the vagabond’s journey. The act of reading becomes then a kind of pilgrim way, the Camino de Santiago traversed with prayer on one’s lips, the way home to Ithaca with Athena, the flashing-eyed goddess, watching over you.

Poems, for me, are the epitome of Dickinson’s capital-L Loneliness, that loneliness that accompanies and keeps one from feeling utterly alone, its shadow-shape, its cameo presence. I’ve often turned to poetry when I’ve felt most alone. When I did a month-long writing residency a couple of weeks after my brother died, I read and read and read Wallace Stevens. When I was unsure about my health, I wrote as many poems as I had time to write.

But I’ve often wondered if my turn to poetry in times of loneliness and uncertainty is a behavior that’s naturally implicit within the genre or if it upholds some cliché notion of what poetry is and should be. Many poets, including my younger self, started writing poetry about their “deepest, darkest” thoughts, their candid internal lives, their feelings. They attempt to render these thoughts and feelings often as abstractions. Of course, this is what I now urge myself away from, putting on the broken record of the one-hit wonder, “Show, Don’t Tell” in my brain.

Once, when I was on a plane, the drunk man at my right elbow had been talking loudly about his job in government cybersecurity to the drunk man in software at my left elbow. Throughout their conversation, I made myself small, trying to avoid the heat of their bodies, which were, as is common, sprawled out in the classic “man-spread” pose. I had a book with me, a book of poetry, and I held my head so close to it that I could see the rough edges of the words’ ink from the printing process. At some point, the drunk man at my right elbow realized that they’d been talking over me without talking to me and he asked me what I was reading. I recalled a moment in graduate school in which my thesis advisor David Wojahn said something like, “If you’re on an airplane and you don’t want anyone to talk to you, read a book of poetry.” The advice was perfect. It suggested that the average person wasn’t interested in talking poetry—it’s hard, it’s too confessional and therefore socially awkward, and/or the person reading it takes themselves way too seriously—and that poetry was a way to preserve solitude, not only in one’s head but also by creating a kind of social barrier, an especially useful tool for those worn out and anxious travelers who just want to get home to their own beds.

I’m sure the man could see that I was reading poetry by the way it was laid out on the page, but he wanted an answer so I flipped over the book and showed him the cover. “Poetry,” I said, thinking it was the end of the conversation and we could go back to pretending that I didn’t know he was drunk.

“Poetry?” he said.

“Poetry,” I said.

“I like poetry,” he said. “What do you do?”

“I’m a teacher.”

“What of?”

“Poetry,” I said.

“Poetry?” he said.

And so it went. Later, after he ordered another double scotch, he told me that he liked poetry because he started reading it after his mother had died, that he read a poem at his mother’s funeral. He couldn’t remember what it was, and, anyway, I had my suspicions that it wouldn’t be anything I found all that compelling (snob that I am—I’m sorry), but I was touched by his attachment to poetry from this moment in which he was lonelied, left alone by his mother’s death.

I started asking myself where most people—non-poets and non-readers of poetry—encounter poetry. High school English (dead white men mostly). Greeting cards. Some might make a case for Bob Dylan. I thought of a cheap print gifted by a family member that said “Fine Wine is like Good Poetry,” the reasons motivating the simile are still unclear to me now, and the Irish Prayer cross-stitch my grandmother had hanging in her dining room. Then some of the occasions for poetry begin to get more meaningful: Psalms. Book of Common Prayer. Presidential inaugurations. Weddings. Funeral programs. Memorial services. Occasions and places of celebration, and those of loneliness, of loss. The only time family members have ever asked me to write poems for them are when they are feeling alone, sad—when they are grieving.

If you go on the Poetry Foundation’s website, you’ll find a category of poems about “Loneliness and Solitude,” and poems about “Anonymity and Loneliness” are listed on the Academy of American Poets. These two websites offer access to many poems for poets and non-poets alike, the casual or occasional reader. I imagine someone typing in “poems about grief” or “lonely poem” into Google and finding their way onto these sites where they can commiserate with generations of poets expressing their infinite loneliness and sorrow and, through reading it, the reader finds a way within and maybe even through their own.

I’ve started collecting lines about loneliness without even realizing what I was doing, the way one might walk a maze without realizing the path from above looks like a star or a cactus or a horse. Larry Levis opens his poem “Ghazal” with the question and its qualification, “Does exile begin at birth? I lived beside a wide river / For so long I stopped hearing it.” Sometimes I worry that the act of reading poetry in my times of loneliness and grief will actually cause it to lose some of its effect, that it will become neutered of its comfort, that the Loneliness poetry offers will become like that wide river I live beside for so long that I stop hearing it. It hasn’t happened yet, but like Dickinson, I feel that I might be lonelier without it, that if there’s ever a time in which I lose my access to or desire for poetry, I will truly be alone, now and forever.

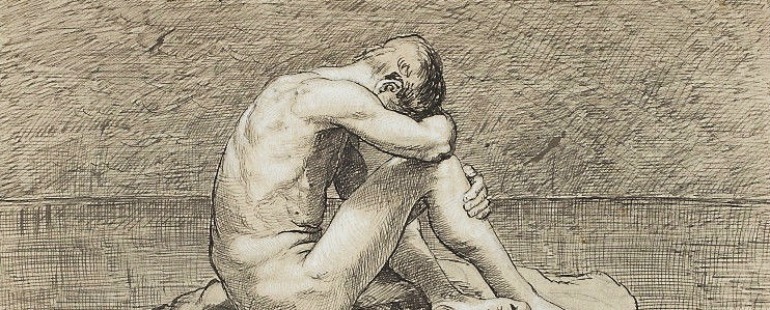

Image: “Loneliness,” Hans Thoma, 1880