Short Stories Are Forgotten Grist for the Hollywood Mill

January means it’s award season for the movie industry. As the nominations and trophies are being passed out, it’s a good time to note how the history of Hollywood is inextricably linked to the history of literature. Of course, the transition from page to screen has not always been smooth–just ask Stephen King (more on him in a moment)–but there have been a slew of successful films from Shakespeare’s works, and great books like Sense and Sensibility, Schindler’s List, Dr. Zhivago, and The English Patient have been the templates for equally memorable motion pictures.

This year, the films being mentioned as possible Best Picture contenders are pulled from a variety of sources: plays, fiction, non-fiction, and screenplays. An often overlooked source of inspiration for movies is short stories. Only one of the 2017 Oscar favorites, Arrival, is based on a short story–Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life.”

Nevertheless, short stories have been fertile ground for superb movies of distant and recent vintage. Individual stories like Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol,” H.G. Wells’ “The Invisible Man,” and “The Most Dangerous Game” by Richard Connell have been interpreted in numerous ways in the transition from page to screen. There is no magic formula for turning a successful short story into a successful movie, but the best examples of doing so share a commitment to staying true to the source material.

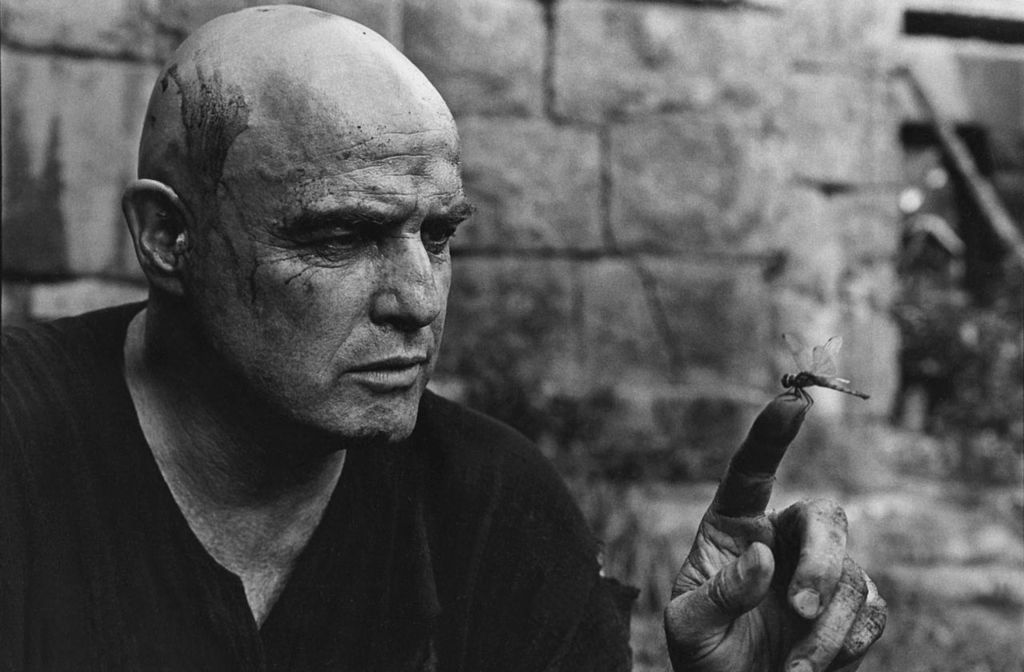

That’s certainly the case for Francis Ford Coppola’s classic Apocalypse Now. Released in 1979, Coppola’s film is a version of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” which was published first as serial and then as a novella some eighty years earlier. The plot centers on a boat captain’s journey down a river to retrieve a man who’s gone mad and transformed himself into a god-like figure to native peoples. In the original story, the setting is the Belgian Congo. Coppola updated this to Cambodia and Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

Apocalypse Now is considered one of the greatest films of Hollywood’s second Golden Age, a period from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. It was a departure from earlier war movies that traditionally featured battle scenes, military strategy, and unapologetic patriotism. In contrast, Apocalypse Now is a mood piece about surviving amid horrific circumstances. Martin Sheen’s boat captain, exhausted but manic, can understand how someone can go mad. On this level, he connects with Kurtz, famously portrayed by a bald, overweight Marlon Brando. The journey down the river is of course the central metaphor in the film, but the characters’ relationships to insanity powers the story.

Achieving the desired mood in the film was not difficult, as the production had taken on a mythical status, with the hard-driving Coppola going well over budget and Sheen suffering from a heart attack (all of which is captured in the documentary, Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmakers’ Apocalypse).

A journey of a different kind takes place in Stand by Me, the 1986 film based on Stephen King’s “The Body.” One of the few successful King-inspired films, Stand by Me tells the story, set in 1959 Oregon, of four pre-teen boys. They embark on foot to see the dead body of a local boy who’s gone missing. En route, they bond, make memories, and learn about themselves. The nostalgia-driven plot was hardly innovative, even in 1986, but Rob Reiner’s assured direction and River Phoenix’s star power along with the eponymous Ben King song playing on the soundtrack tapped into a widespread desire among many Americans for simpler times.

Simple would not describe 2000’s Memento. Christopher Nolan’s second movie was one of the internet’s first word-of-mouth hits. The story–a man tries to figure out who murdered his wife–is straightforward. The way it unravels is anything but. The protagonist, played by Guy Pearce, has short-term memory loss, so he covers his body in tattoos with important pieces of information. Further complicating things, the narrative arc of Memento is not linear–the movie starts at the end. These contrivances allow Nolan to flex his cinematic muscle.

Timing also played a role in the short story that inspired Memento. It was written by Christopher’s brother Jonathon, who told him about his idea, prompting Christopher to write a screenplay. The irony is that the story, “Memento Mori” wasn’t published until 2001, after the movie had already been released. That it took longer to publish a short story than to make a movie won’t come as a surprise to fiction writers.