The “fall” of “The Hollow Men”

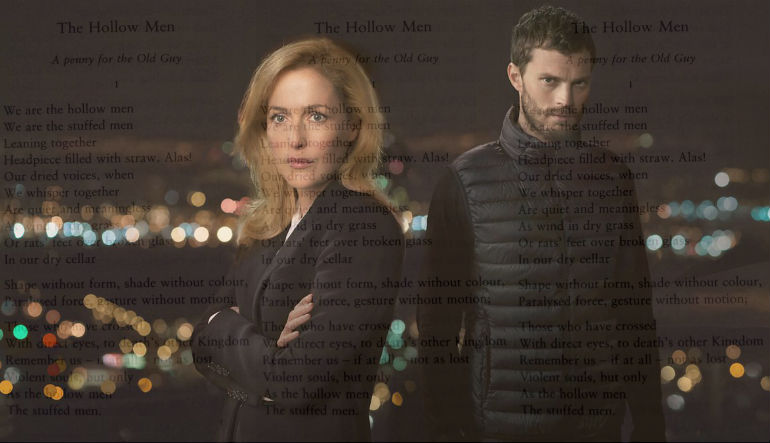

When I first started watching BBC’s serial killer drama The Fall, I was excited to discover that the episode titles were all famous lines from Paradise Lost. After Paul Spector kills his first victim, the episode title references Milton’s infamous description of hell: “Darkness Visible.” When Paul reveals that he began to take pleasure in others’ suffering in order to cope with his own, the episode title quotes one of Satan’s most notable lines: “The Mind Is Its Own Place.” And the series finale, which sees both Spector and Lieutenant Gibson fall from grace in some form or another, is fittingly called “Their Solitary Way.”

But as it turns out, the title is also a reference to another, very different classic poem: “The Hollow Men” by T.S. Eliot. In the third episode of the first series, Paul Spector writes lines from the poem in his handy serial killer notebook:

Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow.

The “fall,” in this case, does not refer to a fall from grace, but to the existence of a “shadow” that lies in the liminal space between impulse and action. “The fall” is the opaque part of Paul Spector’s brain on which the series sheds light—the part that drives him to realize his dark fantasies with living, breathing human beings.

In this sense, the “fall” of “The Hollow Men” is a much more apt allusion than the “fall” in Paradise Lost. In Milton’s poem, Adam and Eve “fell” from an innocent, morally pure state to a knowledgeable, sinful state. When we meet Paul Spector in The Fall, he’s already very much a predator, and has already committed acts that are beyond redemption. The “fall from grace” that occurs is much more abstract; rather than watching a morally untarnished person succumb to evil impulses, we’re watching a morally compromised person slowly integrate his compartmentalized evil impulses into his deluded self-image. Where Adam and Eve’s fall is literal and somewhat external, the “fall” in “The Hollow Men” takes place entirely within the mind.

The conception of sin in The Fall is also much more comparable to “The Hollow Men.” Where Milton’s epic concerns original sin—a moral impurity that is inherent to every person at birth—Eliot’s poem attributes the “fallen” state to a more modern ennui that is directly related to personal guilt and despair. In “The Hollow Men,” the narrator is passing into the heart of hell, not because he was ignorant or even impulsive, but because he consciously chose to reject his better angels. Similarly, The Fall seeks to explain the causes of Paul Spector’s nihilistic worldview, but not to portray him as some kind of redeemable “lost soul.” Instead, he is just a figure to be pitied but never excused, a man who may not be evil but is definitely “hollow.”

Those who have crossed

With direct eyes, to death’s other Kingdom

Remember us-if at all-not as lost

Violent souls, but only

As the hollow men

The stuffed men.

While the ending of The Fall‘s third series was controversial among critics and fans alike, it’s perfectly justified in light of the “Hollow Men” comparison. The final stanza, which consists of some of the most oft-quoted lines of poetry in the English language, argues that in a world full of disenfranchised, spiritually empty people, there is no justice, and therefore no room for real closure. It beautifully predicts a viscerally unsatisfying conclusion, because satisfaction is far too much to expect from hollow men. We don’t get a fitting end.

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.