The Maternal Gothic in The Push and Beloved

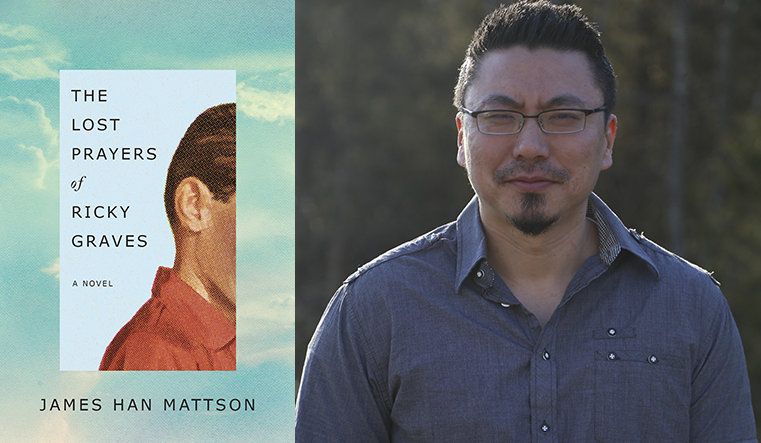

Halfway through Ashley Audrain’s debut novel, The Push, out earlier this year, the main character, Blythe, says, “Mothers aren’t supposed to have children who suffer. We aren’t supposed to have children who die.” Mothers are tasked with keeping their children safe—but, of course, death and suffering are always there, the inevitable outcomes of every life. This paradox is at the heart of maternal gothic novels, a sub-genre in which authors use and adapt the gothic novel’s tropes to explore taboos about motherhood; their narratives dwell on the threats posed both to and by children and mothers, upending idyllic, peaceful visions of maternal life. Maternal gothic novels focus on protagonists’ experience of isolation, tyranny, entrapment, and taboo, also making the form well-suited for explorations of oppression and power. The Push and Toni Morrison’s Beloved were both written in the maternal gothic tradition, and both novels use the form to explore how mothers are devalued and isolated by white, patriarchal power structures.

At the beginning of The Push, Blythe sits outside her ex-husband’s house, watching his new family prepare for Christmas. Her child, Violet, peers out the window, and immediately we feel Blythe’s isolation, understanding that she has been excluded from the idyllic family life. Blythe wants to drop off a letter to her ex-husband, Fox. This letter, written as a second-person account, forms the bulk of the novel’s text. Since most of the narrative present takes place with Blythe sitting alone outside the house—on Christmas Eve no less—the novel promises to outline Blythe’s downfall as wife and mother, to reveal how she came to be excluded and alone.

Fox is the white male gaze personified, and his implied ghost-like presence is a tyrannical force that shapes and distorts the whole novel. All of Blythe’s thoughts are angled towards Fox, as she explains what went wrong in their family. Throughout, Fox is characterized as a cheerful, white, middle-class man, with all of the stereotypical strivings of his race, class, and gender. We are witness to how Blythe internalizes his judgments, measuring herself against his wish for her to be a “normal” white, middle-class mother who submits to motherhood, unburdened by thoughts of loss, disappointment, and struggle, free of desires for independence and freedom.

The isolation and anxiety of white, middle-class motherhood is at the center of The Push. After Blythe gives birth, she struggles to bond with her daughter and spends long days trapped with an infant who won’t stop crying. The only help that comes, a night nurse hired by Fox’s mother, is soon taken away. Fox’s mother, who had herself been a happy stay-at-home mom, withdraws the support after a couple of months, telling Blythe she should be able to do it on her own by now. At every turn, Blythe is shamed for needing help. The two mother’s groups she joins only deepen her isolation and anxiety, as the women do not speak of difficulties or feelings of dissatisfaction or dread, instead spouting platitudes about how it’s “all worth it” and sharing recipes for organic cleaners. As Fox and Violet bond, Blythe is further excluded, her isolation increasing as she is unable to find solace in family or friends.

The only reprieve Blythe finds is in writing while her daughter naps. Soon, she habitually leaves Violet in her crib to cry, for hours sometimes, while Blythe listens to music and writes. The neglect echoes the neglect her grandmother showed her mother, and the neglect Blythe’s mother, in turn, showed her. Just like Blythe, her mother and grandmother were not extended the community support that might have mitigated their own shortcomings as mothers. When Fox discovers the neglect, he is furious but offers no practical help. Blythe tries to make amends by re-doubling her effort to perform the role of “perfect” mother.

As Violet grows, Blythe is increasingly disturbed by the girl’s cold-heartedness. Fox is dismissive, unwilling to hear criticism of his daughter. When Violet is 4, a teacher expresses concern over the easy cruelty Violet inflicts on other children. A few weeks later, Violet tells Blythe she wants to hurt a boy at school. The next day, Blythe finds a clump of hair in Violet’s pocket, and when she sees the boy again, he cowers from her daughter. Not too much later, on the playground, Violet trips a child who falls to his death. Blythe is witness to the murder, and she is certain her daughter killed the child on purpose. Blythe does not say anything but lives with increasing dread about her daughter. She is alone in this knowledge, and her daughter takes on a menacing, tyrannical quality.

Audrain sets up a wild goose chase as she invites us to consider the source of Violet’s violence. The novel opens with a discussion of bloodlines, and we’re told that the women in the family “are different,” inviting questions about genetics. Then, when Blythe neglects Violet, we are to consider if it’s really “nurture” (or the lack of it) that causes Violet’s behavior. Of course, if we declare neglect the root cause, then we need to equally condemn Fox and his mother, as they both fail to intervene in the situation. But this points to a third option. Given that the novel carefully outlines how a white, middle-class, nuclear family structure failed Blythe’s mother and grandmother, just as we see it failing Blythe and Violet, rather than instinctually blaming mothers, we should consider family structure as a potentially compelling root of the problem.

After Blythe gives birth to a son, Sam, their family life clicks into place. Blythe bonds easily with Sam, and Violet is similarly enamored. Blythe “started to take this new, peaceful normal between us for granted” and “could barely remember the mother I had been,” referring to the difficulties she experienced when alone with Violet. After a few months, however, Blythe enters Sam’s room for a middle of the night feeding, and Violet’s voice emerges from the dark, like “a threat” commanding her to put Sam down. Audrain writes, “My chest began to tighten—that feeling again, the creep of anxiety. It was back in an instant, like she snapped her fingers to wake me up from her spell. That tone used to haunt me.” Violet’s presence in Sam’s room is as terrifying as any ghost. Blythe worries Violet might harm Sam, but Fox dismisses her, saying, “You’re probably making something out of nothing. Again.”

Shortly after this incident, Violet tells Blythe she is tired of Sam. And then, one day as they are standing on a street corner, Violet knocks Blythe’s hot tea from her hand. Blythe lets go of Sam’s stroller, and it rolls into traffic, killing him instantly. In the description of the moment as it happens, Violet’s pink mittens are not on the stroller’s handlebar. It is only after, as Blythe recounts the story to herself, that the pink mittens appear on the stroller, pushing it into traffic. Blythe explains what happened to Fox and the police, but they refuse to believe her. Her report is so taboo nobody is willing to listen. The reader is left with uncertainty because we have seen the story shift in real-time. Of course, our own memories work in this way too—noticing and reconstructing impressions into narrative only after the fact.

It isn’t until the novel’s last line, written in third person and finally free of Fox’s presence, that we learn Blythe was right about her daughter all along. These last words force the reader to examine how easy it is to slip into interpretations that frame Blythe as hysterical or delusional, asking us to re-evaluate how we came to distrust Blythe in the first place. Our doubt mirrors the way mothers are often doubted and come to doubt themselves.

Beloved, perhaps one of the most famous novels written in the maternal gothic tradition, represents motherhood and family quite differently from The Push, and this difference has everything to do with race and class. The overlap between the two novels lies in how they use genre to critique social structures that isolate mothers and force us to raise children alone, without the support of community and family. In The Push, we are shown how children can become sources of anxiety, terror, and entrapment within white, middle-class, nuclear family structures, in which it is taboo to need help. In contrast, in Beloved, children and family are sources of joy and support. The children offer hope to Sethe, the novel’s main character, prompting her to run away from the Sweet Home plantation to escape slavery. When they are free, she delights in her children’s presence, overflowing with maternal abundance. In this context, mother-child love is a bold act of defiance against slavery. Although her husband has been lost during their escape, Sethe finds family support living with her mother-in-law, Baby Suggs, who shares caretaking responsibilities. Members of the community frequently drop by, also contributing to family life. In the twenty-eight days that Sethe spends free and in community, we see a fluid family model that supports mothers and children.

The source of horror and entrapment in Beloved is the system of white supremacy that alternately commodifies and devalues black motherhood. Beloved employs a traditional gothic setting, as Sethe and her only remaining child, Denver, live alone in a house haunted by the ghost of Sethe’s dead baby. Prior to her child’s death, the house is a place of joy and gathering, a place where people come to be healed and find solace and solidarity. Twenty-eight days after Sethe’s arrival, they throw a large party, one that springs entirely from the community’s bounty and Sethe’s joy at being a mother who is finally free to love her children whole-heartedly. The next day, the townspeople grow jealous, misguidedly wondering why Baby Suggs and Sethe should have more than everybody else. As a result, when Schoolteacher, the white slave owner from whom Sethe has escaped, arrives intending to kidnap and enslave Sethe’s family, the community fails to warn her. Seeing Schoolteacher, Sethe’s mind returns to the night of her escape, when she was brutally raped. She runs to the shed, choosing to murder her own child rather than see her enslaved. From the outset, we are told the baby’s ghost isn’t angry, only sad. Disruptive though it may be, the ghost is not the source of the novel’s horror, but rather the result of horrors inflicted by the living.

The ghosts of both novels are sources of comfort, offering access to lost love and possibility. Blythe lays out Sam’s clothes to conjure him as a ghost she can hold and love. When she creates a fake identity to befriend Fox’s wife, she makes up stories about Sam and feels that she has brought him back to life. In contrast, “when Violet was with me it was like living in the house with a ghost.” Violet, alive and well, torments her as deliberately as any malevolent ghost. In Beloved, Sethe accepts the ghost’s presence. When she realizes that her dead daughter has returned as Beloved, a teenage girl who shows up in her yard, she loves her fiercely. It doesn’t matter to her that Beloved eventually becomes tyrannical, demanding nothing less than Sethe’s total destruction.

At the end of the novel, the community brings Sethe’s older daughter, Denver, and Sethe back into the fold, coming together to exorcise Beloved’s ghost. It is an act of solidarity and a recognition that Sethe and Denver cannot survive without the extended community to support their family. Even though Beloved was too demanding, too mercurial, after the exorcism Sethe is bereft, mourning the loss and wishing for Beloved’s return. Unlike the living, the novels’ ghosts mitigate the protagonists’ loss of freedom and connection, offering the mothers non-judgment and second chances. In both novels, the horror is, instead, found in the fallout of white western culture’s failure to adequately support mothers and children, whether out of benign neglect or active malice.

This piece was originally published on April 21, 2021.