Big Picture, Small Picture: Context for Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express

This blog series, Big Picture, Small Picture, provides a contextual collage for a chosen piece of literature. The information here is culled from newspapers, newsreels, periodicals, and other primary sources from the date of the text’s original publication.

The impossible could not have happened, therefore the impossible must be possible in spite of appearances.

—Hercule Poirot

Winter storms blast Europe in February of 1929, burying metropolises and rural towns alike under layers of snow. Steamers filled with supplies become stranded in frozen rivers, depriving citizens of much-needed resources. In Paris, the fuel feed pipe of the Arc de Triomphe freezes, causing the Eternal Flame of Remembrance to flicker and die out. In the Balkans, “wolves maddened by hunger” maraud the streets, while brave residents form “vigilance committees” to keep the predators at bay.

Declaring war on mother nature, French military engineers hurl dynamite at the Marne, and Yugoslav soldiers fire cannons at the Danube. Russia deploys two ice-breaking ships, the Truvor and the Yermak, to liberate German shipping vessels in the Kiel Canal.

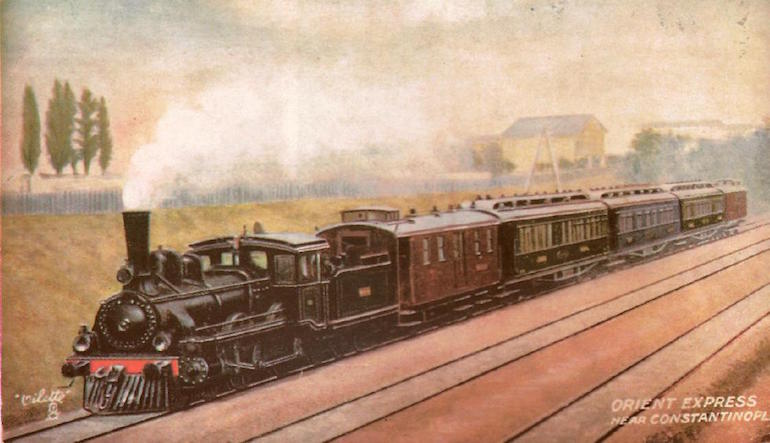

Elsewhere in Europe, the Orient Express, the first name in luxury rail travel, is stopped in its tracks by a snowdrift seventy-five miles outside of Istanbul. The wealthy and powerful passengers, among them royal messengers and government dignitaries, huddle for warmth as the power goes out and the temperature drops below zero. A force of one thousand laborers and soldiers attack the ice with picks, axes, and shovels while packs of wolves watch from the woods around them. After eleven days, the train finally lurches to life and rolls into Istanbul, a city on the edge of famine.

British mystery writer Agatha Christie follows the news of the ordeal with interest, using the circumstance for her classic novel, Murder on the Orient Express, first published in the U.K. on January 1, 1934. In the novel, Christie’s famous Belgian detective, Hercule Poirot, travels aboard the Orient Express when the train comes to a halt in a snowstorm in the middle of the night. The next morning, Poirot is presented with an interesting crime scene; a man in the cabin next-door has been stabbed, and every passenger on the train is now a murder suspect.

Poirot employs his “little gray cells” to discover that the dead man was an American criminal who was attempting to flee justice for his involvement in a high-profile kidnapping and murder of a young child. As the lights in the Orient Express flicker and die and the temperature plunges, the little detective conducts his investigation, learning that certain passengers are hiding their connections to the victim. The more Poirot uncovers about the crime, the more he suspects that the murder was an act of private justice.

Two years before the iconic mystery is published, on the night of March 1, 1932, Charles Lindbergh III, the toddler child of famous aviator Charles Lindbergh, is kidnapped from his bedroom in New Jersey. A ransom note in the empty crib demands $50,000, and a massive investigation ensues. On September 19, 1934, sixteen months after the body of the young child was discovered only five miles from the Lindbergh home, authorities arrest German-born carpenter Richard Hauptmann for the crimes, thus beginning the “trial of the century.”

Though Hauptmann professes his innocence to the very end, he is convicted and sent to the electric chair on April 3, 1936. “Justice has been served,” asserts the prosecution.

Once Poirot sleuths out who is responsible for the death of the American criminal on the Orient Express, he is faced with a detective’s dilemma: in this case, what is the best way to “serve justice”?

Ten months after Murder on the Orient Express is published, a real-life murder mystery unfolds in a train yard in Cincinnati, Ohio. The body of a man is found in a passenger car as it rolls into the station; the only clue is a pair of shoes next to the man that does not appear to be his. Police search for a suspect wearing the dead man’s shoes, but ultimately the assailant eludes justice.

Murder on the Orient Express is Christie’s tenth Hercule Poirot mystery, and she will go on to write over forty books featuring the fastidious private detective. On August 6th, 1975, the front page of the New York Times proclaims, “Hercule Poirot is Dead.” Indeed, Poirot meets his end in Christie’s Curtain, having investigated countless murders in a career that spanned decades (by some timelines, Poirot was 125 years old when he died).

In the end, rather than clinging to a rigid definition of justice, Poirot embraces the gray area: “There are more important things than finding the murderer. And justice is a fine word, but it is sometimes difficult to say exactly what one means by it.”