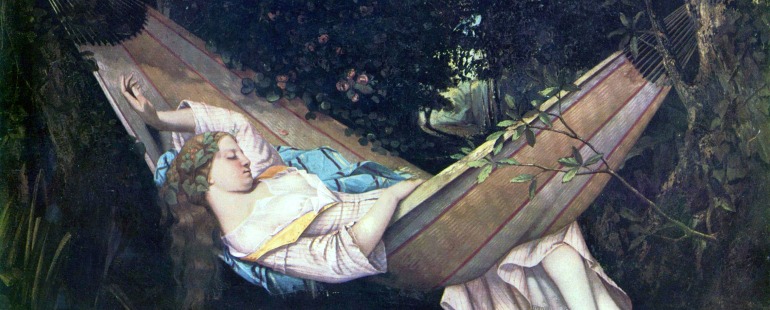

Lying in a Hammock

Reader, I am having a bad day. I am having a bad day, and I can’t seem to write anything worth your time, and so I have flipped through my books and settled on James Wright’s “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota,” because it is one of those foundational poems I puzzled over in school and have tended to return to when I am stuck, uninspired, or otherwise feeling frustrated by trying to write poetry.

I return over and over to the handful of first poems I learned important lessons about poetry from, in hopes that there will be something new still left to discover there or, at least, that its particular music will still hold some power after a million or so re-readings.

Wright elevates nature to a focal point and contrasts natural beauty with his darker feelings about the himself and humanity. Beginning with the speaker looking up from his position in the hammock to remark upon a butterfly overhead, the poem seems at first to simply be a nature idyll, sort of a pastoral, one in which even horse dung is worthy of poetic attentiveness:

In the field of sunlight between two pines,

The droppings of last year’s horses

Blaze up into golden stones.

This is a borderline comical or questionable moment, lauding horse shit, but certainly not an especially surprising one, and the poem continues afterward predictably enough, with the speaker leaning back and focusing next on a bird in the sky. Wright is casting about for something to tell you about next, because he does not know what to say, or perhaps, reader, that is me, I don’t know what to say next, and I am hoping that this poem I love will bail me out once more.

I lean back, as the evening darkens and comes on.

A chicken hawk floats over, looking for home.

Again, this is pretty standard stuff, with the sunset and darkening sky signaling thoughts of mortality, the usual what-does-it-all-mean poetic fodder, and ordinarily to be honest, I don’t really go in for nature poems very often. And Wright—I like to think that what comes next was the part of the poem he struggled most over, that he crossed out couplet after couplet and tossed the whole thing aside more than once before finally landing squarely on the single last line, whole and perfect.

I have wasted my life.

It’s a line that so neatly upends and yet somehow fulfills our expectations of where the poem will end. The poem is free verse, although it loosely adopts conventions of the sonnet form. Place—setting—becomes the poem’s argument, and the volta appears at the end, reduced from a traditional Shakespearean couplet to the single final line. And in spite of its abrupt arrival and flat diction, the ending feels epiphanic. “I have wasted my life,” Wright discovers, laments, even seems to marvel—depending, perhaps, on the reader’s mood when they encounter the line. Like a traditional volta, the line turns the poem’s argument in an unexpected direction.

Some days, the line is wistfully joyous, alluding to the happily wasted hours in hammocks and backyards and couches and beds of leisure. On days when I am stuck—days like today, you understand—the line seems desperate and pessimistic; the poem seems to be about mortality and loneliness, and the futility of writing altogether. Sometimes, the thirteen lines seem to beg to be called a sonnet, the omission of the fourteenth line reinforcing rather than detracting from the poem’s structure, while other times, the poem seems persistently free verse, the number of lines mere coincidence. And there are empty spaces in the poem that resist being one mood or another: the sleeping butterfly and the empty house and the cowbells that stand in for absent cows. It all wavers on the page, and I am troubled, because my own ideas are wobbling gray and unformed in my mind and there’s space for this, too, in Wright’s poem, which after all is only a man lying in a hammock alone, as around him, darkness falls.

The house is empty, and nearly all of the animals have gone.

Image: “The Hammock” by Gustave Courbet, 1844