M. & Mme Bovary the Romantics

I first read Madame Bovary in high school. I found Emma whiny and annoying like I probably was and couldn’t see too far past her image. I didn’t remember her husband Charles at all, and I definitely had no feelings for him. Who would? He’s the main reason she resorts to arsenic. At least I used to find the situation so transparent.

After a recent viewing of the 2014 movie version starring Mia Wasikowska, I picked up Lydia Davis’s 2010 award-winning version of Flaubert’s famous realist novel. This time around the book is markedly different, perhaps in part thanks to Davis’s expert hand. Now it’s Charles I remember. His world is Romantic like Emma’s, at times veering on Gothic. His darks are perhaps even darker than hers. The same goes for his lights. It’s a far cry from the staid front lines of the realists, where many literary critics place Flaubert.

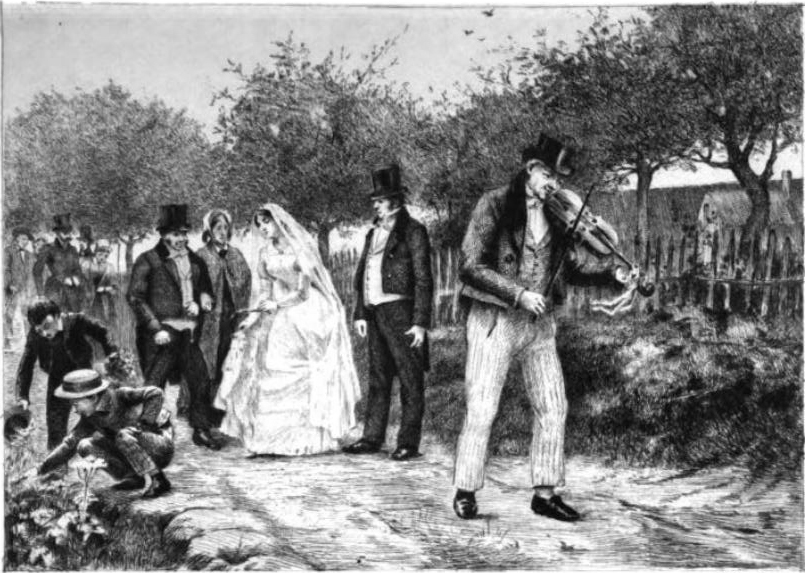

Believe me, I didn’t see this coming. The kind doctor is forgettable in the recent movie version. On screen, it’s all Emma and sumptuous warm-colored dresses. On the pages of Davis’s Flaubert, I’m surprised to see a teenaged Charles begin the story. His clothes are too bright, too small, and he’s the new boy in school. We’ve all been the new kid. His relationship with his mother is revealed to be Oedipal at worst. Most parents hover and push us to marry or couple up. Next he weds a bony, unattractive widow who abruptly and somewhat mysteriously dies. The comparisons stop here for me—and probably you—too.

Then something wonderful happens: In breezes Emma. Charles falls swiftly for her. My heart goes out to him.

Emma’s transformation is quick. She moves from country girl to elegant woman with a taste for expensive household goods and fashionable clothing. Her romantic machinations fuel the story. Charles plods alongside her, his two blind eyes turned to her multiple affairs. Only after Emma poisons herself is it clear how much he truly cares: “And he looked at her with a love in his eyes that she had never seen before.”

Then something terrible happens: Out breezes Emma, who experiences peace and religious ecstasy at her own death. Again, I hope the best for Charles, but the dark, Gothic clouds have already appeared.

This time, it’s Charles who transforms. He adopts his dead wife’s extravagant taste, demanding a rich green velvet fabric be thrown over her corpse. Unlike Emma’s other lovers Leon and Rodolphe, who sleep soundlessly the night of her funeral, “…Charles, awake, was still thinking of her.” Her ghost haunts him. He sits across from her chair as though she’s still in it. He fancies the maid wearing one of his dead wife’s dresses is Emma and even speaks to her. He purchases expensive shoes and styles his mustache in the way she once preferred.

So far there’s been death by poison, a spiritual experience, ghostly hauntings, and the clothes of the dead confusing the living. Still, no Gothic tale would be complete without a dependable recluse.

Here we find Charles hiding away, the village thinking him an alcoholic. He grows out his beard, dresses shabbily, and audibly expresses his grief. Published a decade after Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, Charles’ grief brings Heathcliff to mind. If only the doctor had acres of English Moors to roam rather than a compact French garden to pace.

In the novel’s final pages, Charles shares a spontaneous beer with Rodolphe. Charles, finally forgiving his dead wife’s adulterer, shares his one great phrase with the man: “Fate is to blame!” With this one brief statement, Charles buys into the notion of fated lovers, not a far cry from that of soul mates, another Romantic hallmark.

The next day, Charles sits on an outdoor bench and takes his last breath, all while clutching a lock of Emma’s dark hair. An autopsy reveals nothing physical to blame. It’s safe to assume he dies of a broken heart.

It’s not the fate you’d expect for the awkward new boy in school, and perhaps that’s Flaubert’s (and Davis’s) intent. In Madame Bovary, similes are sparse, scenery contained, and dialogue brief. In the end, Emma and Charles are both wrecked with romantic desire. Emma’s death relieves her longing and allows Charles to fully realize his own. Perhaps the problem is that Emma reads too many Romantic novels and Charles too few.

One of Bovary’s poetic motifs is the Blind Man who roams around the provincial village, uncured by Monsieur Homais, the pharmacist. On her deathbed, Emma hears the Blind Man’s refrain from the sidewalk below her window:

“’How oft the warmth of the sun above

Makes a pretty young girl dream of love.”’

The foreboding in the blind man’s words is, to use A.S. Byatt’s from a 2002 Guardian piece on Madame Bovary, “both terrifying and simultaneously gleeful over its own accuracy.”

Flaubert’s novel begins realistically enough with a clumsy young boy dressed in garish colors and a pretty young girl dreaming of love. In the end, love, turned Romantic and Gothic, devours both Monsieur and Madame Bovary, Charles perhaps all the more cruelly.