Unripe Fruit in Rural Poland

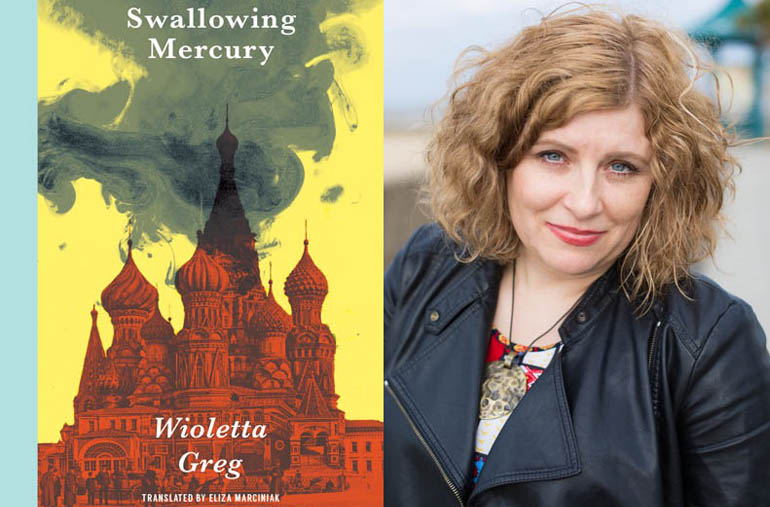

In small-town Poland in the 1980s, getting a dress made can take months due to shortages, but the dressmaker will make you tea, offer you cake, and tell your fortune while you wait. This is the setting of Swallowing Mercury and its protagonist Wiola’s coming of age. Swallowing Mercury, translated by Eliza Marciniak, is the semi-autobiographical novella from the Polish poet Wioletta Greg. It’s a brutal childhood, with hard knocks both physical and metaphorical: a farmhouse building falls on her, she passes out in a snowdrift. Through it all, Wiola is a clear-eyed tour guide narrator, blasting the reader with the harsh reality of her bildungsroman while simultaneously giving a close-up view of the isolated world she was born into.

Books with rural settings seem to be magnetically drawn to focusing on family. Part of it is the isolation leaving limited options, part of it might be the association between small towns and the conservative, traditional family structure. But it’s also richly dramatic: characters are not just at a remove from larger society, but they’re trapped with people whom they did not choose, whom they have little control over. Here, Wiola’s family might not be on the majority of the pages, but they are definitely the center of gravity for the work.

The first chapter deals with the absence of Wiola’s father at the beginning of her life. He was a soldier, and the first time he sees his daughter, he “cried for the whole day, and he calmed down only when Poland started playing in the World Cup.” Wiola’s father looms large throughout the text. He’s a rural Renaissance man: a hobbyist taxidermist, a beekeeper, an amateur magician. He always loses at cards but is ashamed to not continue to play with his friends. Young Wiola loves him dearly, but from an insurmountable distance. Greg is smart enough to deploy him sparingly, but when she does, his appearances can be devastating. In one scene, out of nowhere, he makes the pronouncement that, “Before I’ve even had time to blink, they’re already calling me old, when inside I’m like an unripe fruit.” “Unripe Fruit” was the original title of the book, Guguły in Polish.

Her father is missing from many chapters of the book, not just from the pages but from the places where Wiola needs help, needs protection. And Wiola has to face a lot in her small world, though the setting itself only goes as far as to give her splinters. It’s the people around her that besiege Wiola, pushing her down every time she emerges from the safety of her home. The book’s title is not metaphorical; Wiola deals with the trauma she faces by eating fringe from a sofa, burning her possessions, and drinking the mercury from a thermometer.

This novel pairs brilliantly with History of a Disappearance, a recent nonfiction book chronicling the history of the Polish town of Miedzianka, located in the same southwestern corner of the country as Hektary. While that book gave a journalist’s bird’s-eye view, Swallowing Mercury offers the ground-level, zoomed-in view. In both books, the communities depicted echo with the pain from World War II and hardships under Soviet rule, and the shared trauma interplays meaningfully with Wiola’s personal trauma. When a girl in the village begins wandering the fields at night, shouting and waking people up, it’s explained as her being chosen to continue dreaming the dreams of those killed by Germans. The people of Hektary have little to take pride in, so instead they pour their energy into little victories: an art competition, a military hero tribute, or the possibility of their fellow countryman Pope John Paul II driving through the town on his way elsewhere in Poland. The women of the village band together to create a chain of colorful fabric to decorate the road and anticipation hangs heavy in the air. Such high hopes, the reader knows, can only lead to disappointment.

Swallowing Mercury hangs together on Wiola’s voice. She doesn’t dwell on interiority, instead communicating her emotions largely through what goes unsaid. When a chapter ends with a beautiful description of an infected splinter—“The splinter under my skin, with its crimson halo, throbbed and oozed poison into a two-inch read streak”—it communicates so much more than the state of a piece of wood in her skin. The style here mirrors the content: Wiola describes feeling like a cat was an important childhood mentor, and grows up in a world that has little use for beating around the bush. The narrative voice reflects and amplifies this life.

Greg also expertly portrays the logic of a child. When her mother gives Wiola money for the collection plate at church, and Wiola prays that she’ll resist the temptation of the ice cream man. Greg doesn’t show Wiola buy the ice cream. Instead, the narration cuts straight to her holding a cone as she walks away. Her voice is direct, matter-of-fact, and constantly zooming in on the strange things around her while simultaneously not being surprised by them.

Like History of a Disappearance, Swallowing Mercury offers a view into rural Poland that surprises with both the familiarity and the difference. Its child protagonist offers a frank perspective centered on an emblematic familial experience and Greg’s poetic sensibilities exquisitely render Wiola’s small town all the way through a beautiful closing paragraph. Hektary is buffeted by forces too large for it to resist—history, the economy, social structure—but still exists as something unique, something more than the sum of its parts.